These are certainly exciting times for Tesla (NASDAQ:TSLA). The first production version of the Tesla 3 was unveiled on July 28, with few surprises on the details, but plenty of good reviews. Elon Musk was his usual self, alternating between celebrating success and warning investors in the stock that the company was approaching “manufacturing hell“, as it ramps up its production schedule to meet its target of producing 10,000 cars a week. It is perhaps to cover the cash burn in manufacturing hell that Tesla also announced that it planned to raise $1.5 billion in a junk bond offering. Investors continued to be unfazed by the negative and lapped up the positive, as the stock price soared to $365 at close of trading on August 9, 2017. With all of this happening, it is time for me to revisit my Tesla valuation, last updated in July 2016, and incorporate, as best as I can, what I have learned about the company since then.

Tesla: The Story Stock

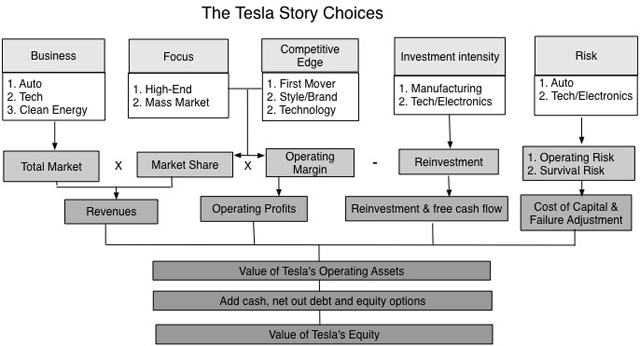

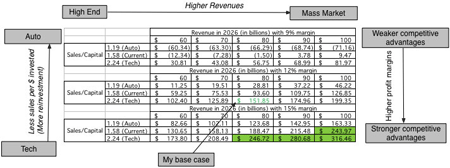

I have been following Tesla for a few years and rather than revisit the entire history, let me go back to just my most recent post on the company in July 2016, where I called Tesla the ultimate story stock. I argued that wide differences between investors on what Tesla is worth can be traced to divergent story lines on the stock. I used the picture below to illustrate the story choices when it comes to Tesla, and how those choices affected the inputs into the valuation.

In that post, I also traced out the effect of story choices on value, by estimating how the numbers vary, depending upon the business, focus and competitive edge that you saw Tesla having in the future:

(click to enlarge)

With my base case story of Tesla being an auto/tech company with revenues pushing towards mass market levels and margins resembling those of tech companies, I estimated a value of about $151 a share for the company and my best case estimate of value was $316.46.

Tesla: Operating Update

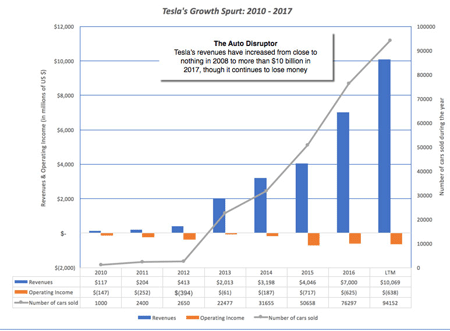

If you are invested in or have been following Tesla for the last year, you are certainly aware that the market has blown through my best case scenario, with the stock trading on August 9, at $365 a share, completing a triumphant year in markets:

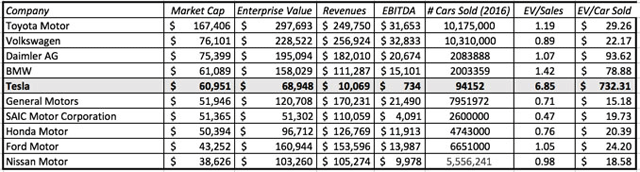

As Tesla’s stock price rose, it broke through milestones that guaranteed it publicity along the way. It’s market capitalization exceeded that of Ford and General Motors in April 2016, and in June 2016, Tesla leapfrogged BMW to become the fourth largest market cap automaker in the world, though it has dropped back a little since. It now ranks fifth, in market capitalization, among global automobile companies:

Largest Auto Companies (Market Capitalization) on August 9, 2017

While Tesla’s market cap has caught up with larger and more established auto makers, its production and revenues are a fraction of theirs, leading some to use metrics like enterprise value per car sold to conclude that Tesla is massively over valued. I don’t have much faith in these pricing metrics to begin with, but even less so when comparing a company with massive potential to companies that are in decline, as I think many of the conventional auto companies in this table are currently.

As I noted at the start of the post, it has been an eventful year for Tesla, with the completion of the Solar City acquisition, and the Tesla 3 dominating news, and its financial results reflect its changes as a company. In the twelve months ended June 30, 2017, Tesla’s revenues hit $10.07 billion, up from $7 billion in its most recent fiscal year, which ended on December 31, 3016; on an annualized basis, that translates into a revenue growth rate of 107%. That positive news, though, has to be offset at least partially with the bad news, which is that the company continues to lose money, reporting an operating loss of $638 million in the most recent 12 months, with R&D expensed, and a loss of $103 million, with capitalized R&D. The growth in the company can be seen by looking at how quickly its operations have scaled up, over the last few years:

(click to enlarge)

Tesla’s growth has not just been in the operating numbers but in its influence on the automobile sector. While it was initially dismissed by the other automobile companies as a newcomer that would learn the facts of life in the sector, as it aged, the reverse has occurred. It is the conventional automobile companies that are, slowly but surely, coming to the recognition that Tesla has changed their long-standing business. Volvo, a Swedish automaker not known for its flair, announced recently that all of its cars would be either electric or hybrid by 2019, and Ford’s CEO was displaced for not being more future oriented. A little more than a decade after it burst on to the scene, it is a testimonial to Elon Musk that he has started the disruption of one of the most tradition-bound sectors in business.

Tesla: Valuation Update

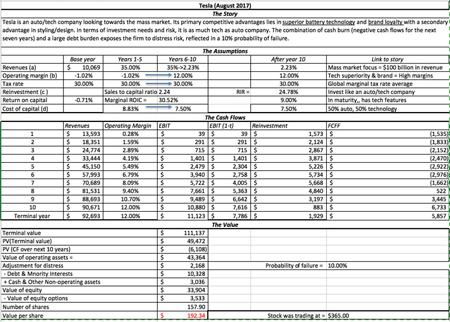

The production hiccups notwithstanding, the company continues to move towards production of the Tesla 3, with the delivery of the handful to start the process. There is much that needs to be done, but I consider it a good sign that the company sees a manufacturing crunch approaching, since I would be concerned if they were to claim that they could ramp up production from 94,000 to 500,000 cars effortlessly. My updated story for Tesla is close to the story that I was telling in July 2016, with two minor changes. The first is that the production models of the Tesla 3 confirm that the company is capable of delivering a car that can appeal to a much broader market than prior models, putting it on a pathway to higher revenues. My expected revenues for Tesla in ten years are close to $93 billion, a nine-fold increase from last year’s revenues and a higher target than the $81 billion that I projected in my July 2016 valuation. Second, the operating margins, while still negative, have become less so in the most recent period, reducing reinvestment needs for funding growth. The free cash flows are still negative for the next seven years, a cash burn that will require about $15.5 billion in new capital infusions over that period. With those changes, the value per share that I estimate is about $192/share, about 20% higher than my $151 estimate a year ago, but well below the current price per share of $365.

(click to enlarge)

As with every Tesla valuation that I have done, I am sure (and I hope) that you will disagree with me, with some finding me way too pessimistic about Tesla’s future, and others, much too optimistic. As always, rather than tell me what you think I am getting wrong, I would encourage you to download the spreadsheet and replace my assumption with yours. I think I am being clear eyed about the challenges that Tesla will face along the way and here are the top three:

- Can Tesla sell millions of cars? One of Tesla’s accomplishments has been exposing the potential of the hybrid/electric car market, even in an era of restrained fuel prices. That is good news for Tesla, but it has also woken up the established automobile companies, as is evidenced by not only the news from Volvo and Ford, but also in increased activity on this front at the other automobile companies. In my valuation, the revenues that I project in 2027 will require Tesla to sell close to 2 million cars, in the face of increased competition.

- Can it make millions of cars? Tesla’s current production capacity is constrained and there are two production tests that Tesla has to meet. The first is timing, since the Tesla 3 deliveries have been promised for the middle of 2018, and the assembly lines have to be humming by then. The second is cost, since a subtext of the Tesla story, reinforced by hints from Elon Musk, is that the company has found new and innovative ways of scaling up production quickly and at much lower costs than conventional automobile companies.

- Can it generate double digit margins? In my valuation, I assume an operating margin of 12% for Tesla, almost double the average of 6.33% for global auto companies. For Tesla to generate this higher margin, it has to be able to keep production costs low at its existing and new assembly plants and to be able to charge a premium price for its automobiles, perhaps because of its brand name.

Tesla has shown a capacity to attract and keep customers and I think it is more than capable of meeting the first challenge, i.e., sell millions of cars, especially since its competition is saddled with legacy costs and image problems. It is the production challenge that is the more daunting one, simply because this has always been Tesla’s weakest link. Over the last few years, Tesla has consistently had trouble meeting logistical and delivery targets it has set for itself, and those targets will only get more daunting in the years to come. Furthermore, if its production costs run above expectations, it will be unable to deliver on higher margins. To succeed, Tesla will require vision, focus and operating discipline. With Elon Musk at its helm, the company will never lack vision, but as I argued in my July 2016 post, Mr. Musk may need a chief operating officer at his side to take care of delivery deadlines and supply chains.

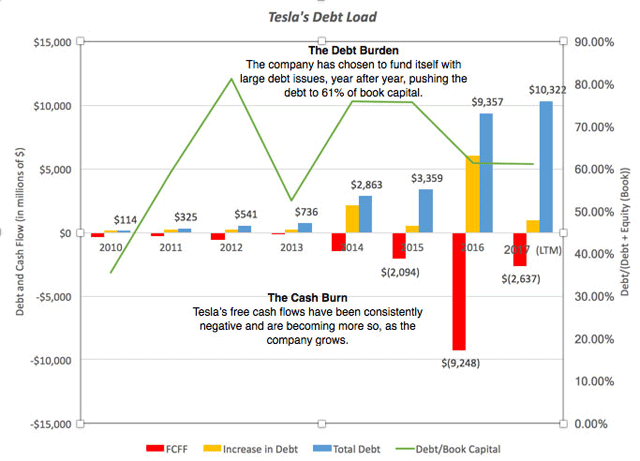

Financing Cash Burn: Tesla’s Odd Choice

There is much to admire in the Tesla story but there is one aspect of the story that I find puzzling, and if I were an equity investor, troubling. It is the way in which Tesla has chosen to, and continues to, finance itself. Over the last decade, as Tesla has grown, it has needed substantial capital to finance its growth. That is neither surprising nor unexpected, since cash burn is part of the pathway to glory for companies like Tesla. However, Tesla has chosen to fund its growth with large debt issues, as can be seen in the graph below:

That debt load, already high, given Tesla’s operating cash flows is likely to get even bigger if Tesla succeeds in its newest debt issue of $1.5 billion, which it is hoping to place with an interest rate of 5.25%, trying to woo bond buyers with the same pitch of growth and hope that has been so attractive to equity markets. That suggests that those making the pitch either do not understand how bonds work (that bondholders don’t get to share much in upside but share fully in the downside) or are convinced that there are enough naive bond buyers out there, who think that interest payments can be made with potential and promise.

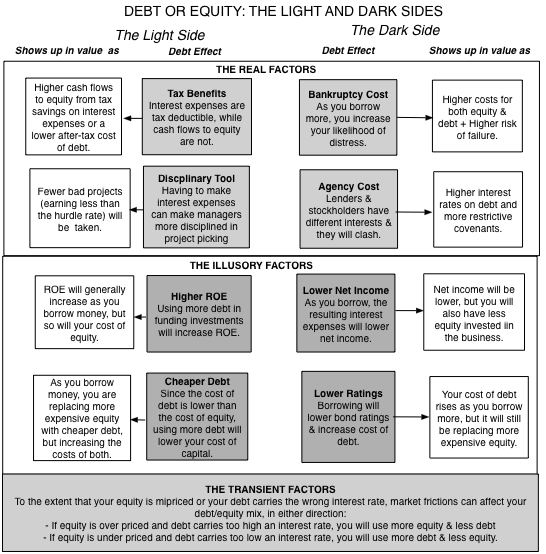

But setting aside concerns about bondholders, the debt issuance makes even less sense from Tesla’s perspective. Unlike some, I don’t have a kneejerk opposition to the use of debt. In fact, given that the tax code is tilted to benefit debt, it does make sense for many companies to use debt instead of equity. The trade off, though, is a simple one:

If you look at the trade off, you can see quickly that Tesla is singularly unsuited to using debt. It is a company that is not only still losing money but has carried forward losses of close to $4.3 billion, effectively nullifying any tax benefits from debt for the near future (by my estimates, at least seven years). With Elon Musk, the largest stockholder at the company, at the helm, there is no basis for the argument that debt will make managers more disciplined in their investment decisions. While the benefits from debt are low to non-existent, the costs are immense. The company is still young and losing money, and adding a contractual commitment to make interest payments on top of all of the other capital needs that the company has, strikes me as imprudent, with the possibility that one bad year could its promise at risk. Finally, in a company like Tesla, making large and risky bets in new businesses, the chasm between lenders and equity investors is wide, and lenders will either impose restrictions on the company or price in their fears (as higher interest rates). So, why is Tesla borrowing money? I can think of two reasons and neither reflects well on the finance group at Tesla or the bankers who are providing it with advice.

- The Dilution Bogeyman: The first is that the company or its investment bankers are so terrified of dilution, that a stock issue is not even on the table. Once the dilution bogeyman enters the decision process, any increase in share count for a company is viewed as bad, and you will do everything in your power to prevent that from happening, even if it means driving the company into bankruptcy.

- Inertia: Auto companies have generally borrowed money to fund assembly plants and the bankers may be reading the capital raising recipe from that same cookbook for Tesla. That is incongruent with Elon Musk’s own story of Tesla as a company that is more technology than automobile and one that plans to change the way the auto business is run.

Tesla’s strengths are vision and potential and while equity investors will accept these as down payments for cash flows in the future, lenders will not and should not. In fact, I cannot think of a better case of a company that is positioned to raise fresh equity to fund growth than Tesla, a company that equity investors love and have shown that love by pushing stock prices to record highs. Issuing shares to fund investment needs will increase the share count at Tesla by about 3-4% (which is what you would expect to see with a $1.5 billion equity issue) but that is a far better choice than borrowing the money and binding yourself to make interest payments. There will be a time and a place for Tesla to borrow money, later in its life cycle, but that time and place is not now. If Tesla is dead set on not raising its share count, there is perhaps one way in which Tesla may be able to eat its cake and have it too, and that is to exploit the dilution bogeyman’s blind spot, which is a willingness to overlook potential dilution (from the issuance of convertibles and options). In fact, why not issue long term, really low coupon convertible bonds, very similar to this one from 2014, a bond only in name since almost all of its value came from the conversion option (which is equity with delayed dilution)?

Conclusion

The Tesla story continues to evolve, and there is much in the story that I like. It is changing the automobile business, a feat in itself, and it is starting to deliver on its production promises. The next year may be manufacturing hell, but if the company can make it through that hell and find ways to deliver the tens of thousands of Tesla 3s that it has committed to delivering, it will be well on its way. I still find the stock to be too richly priced, even given its promise and potential, for my liking, but I understand that many of you may disagree. That said, though, I do think that the company’s decision to use debt to fund its operations makes no sense, given where it is in the life cycle.

Leave a Reply