The U.S. Energy Information Administration last week issued an early release of its Annual Energy Outlook 2014, which shows substantially more optimism about near-term U.S. crude oil production compared to the AEO 2013 assessment completed just eight months ago.

In its April report the EIA was anticipating that U.S. production of crude oil from the tight formations now made accessible with fracking drilling methods would total 2.3 million barrels per day for 2013, and could increase another half-million barrels per day above that before peaking in 2020. But the new assessment is that 2013 tight oil production will amount to 3.5 mb/d– over a million barrels more than the earlier estimate– and will gain another 1.3 mb/d beyond that before peaking in 2021.

EIA’s historical estimates and projected future total U.S. tight oil production in millions of barrels per day as of April 2013 and December 2013

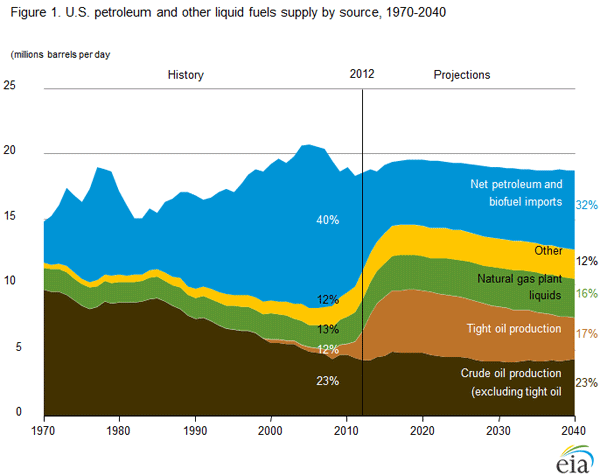

Those numbers along with the EIA’s other projections imply that total U.S. field production of crude oil from all sources would reach 9.6 mb/d in 2019– almost as high as the all-time U.S. peak in 1970– before resuming its decline. If you add in natural gas liquids (which you really shouldn’t) and ethanol produced from corn (which is even less useful [1], [2]), the total would substantially exceed the historical U.S. peak.

Source: AEO 2014.

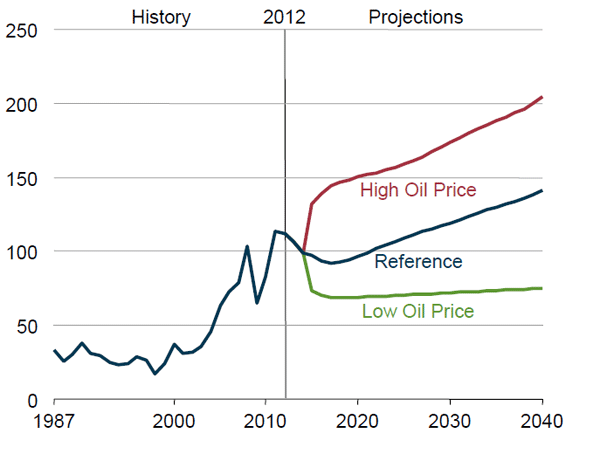

Interestingly, any reductions in crude oil prices associated with this increased production are expected by the EIA to be relatively modest and short lived.

Average annual spot price of Brent in 2012 dollars per barrel. Source: AEO 2014.

Why wouldn’t all this new production have a more dramatic effect on the price of oil? The answer is that, had it not been for the increase in tight oil production in the U.S. and oil sands from Canada, global oil production would actually have declined between 2005 and 2012. And the growth in oil consumption from the emerging economies has eaten up more than all of this new production.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply