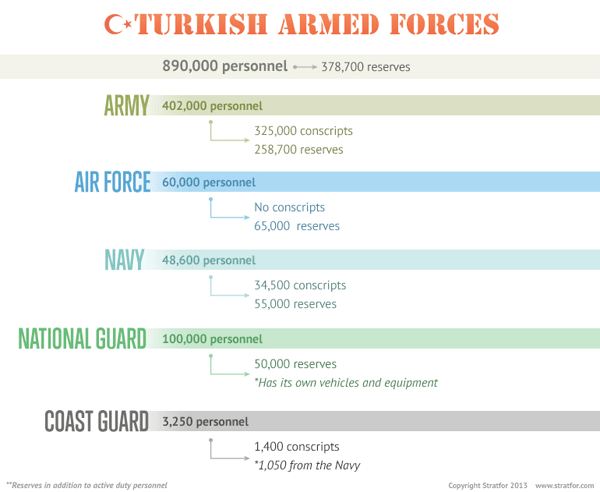

A large, conscripted military may no longer be the most appropriate way for Turkey to protect its interests and defend against external threats. Ankara appears to have acknowledged as much Oct. 21, when it voted to reduce the length of time conscripted soldiers are required to serve. The measure, which will take effect Jan. 1, 2014, will effectively shrink the military by 70,000 members. This is no small diminution, considering that Turkey, with its 750,000 soldiers, has the second-largest military among NATO members. Political and economic considerations may have informed Ankara’s decision, but ultimately the move was made to reflect the changing geopolitical conditions under which Turkey now finds itself.

Analysis

Historically, Turkey’s location and geography has necessitated a robust military. Located at the crossroads between Asia and Europe, the country was critical terrain during the Cold War. In 1952, Turkey became a member of NATO, serving as the southwestern bulwark against the Warsaw Pact. It mustered a large standing military by establishing compulsory service for all Turkish men. Though the Cold War ended two decades ago, Turkey has maintained this practice.

Conscription is mandated by the Turkish Constitution, but the legislature determines how it will be enacted. Currently, a healthy Turkish man with no college education serves for 15 months. Prior to 2003, the minimum requirement was 18 months. The upcoming change will reduce this term to 12 months. Of course, there are some exceptions to the mandate. Men with college education have a shorter commitment of six to 12 months, and men over the age of 30 can buy their way out of service for a fee.

Exemptions notwithstanding, conscripts constitute the majority of Turkish service members, comprising some 500,000 soldiers. With such a short service time, many conscripts fail to gain experience after their basic training. As a result, the Turkish military has a small professional core that is augmented by lightly trained forces.

Old Structures, New Threats

This structure made sense during the Cold War, when Turkey was facing similarly structured Soviet and Soviet-backed militaries. Mobilizing an entire population of even lightly trained service members, should the need arise, certainly has its advantages. But times have changed, as have Turkey’s primary strategic threats. Whereas once the country was confronted with the prospect of a Soviet ground invasion, it now contends with domestic terrorism, Kurdish insurgents and, more recently, border issues with neighboring Syria, still in the throes of civil war. Smaller, more agile professional forces, along with Turkey’s paramilitary forces, are better suited to address these security concerns.

However, force structures are not determined by threats alone. For decades, the Turkish military acted as the guardian of the Kemalist principles upon which the country was founded. Maintaining a large standing army helped the military extend its influence into the political affairs of the state. But the rise and political consolidation of the ruling Justice and Development Party over the past decade has severely undermined the Turkish military’s political influence. The mere sight of once-invulnerable Turkish generals in jail confirms that Turkey’s civilian political leadership has supplanted the military establishment.

Clearly, there is a political element to the conscription reform, as evidenced by the Justice and Development Party’s political consolidation and its imperative to curb the military’s influence. Equally important, a presidential election will take place in 2014 and general elections in 2015. A circumscribed military service requirement will likely buy the ruling party considerable political capital among voters, many of whom would rather study, work and earn a living than perform an increasingly archaic social service.

Aside from political considerations, military modernization and increasingly capable military technology demand that force structures maintain highly trained, professional personnel. New technologies and the requisite personnel operating them require more time and more money. The current conscription model does not address these requirements sufficiently. Therefore, the military is being reconfigured as a smaller, better-trained and more expensive per capita professional force supported by higher-end technological platforms.

This transformation likely will continue for the foreseeable future. Conscription will be modified to the point that it faces elimination, which would probably require a constitutional amendment. Other countries that have undergone similar reconfigurations, including former Warsaw Pact members that later joined NATO, have learned that this process can take decades to complete and that a smaller military is not necessarily a cheaper military.

“Turkey: How Conscription Reform Will Change the Military is republished with permission of Stratfor.”

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply