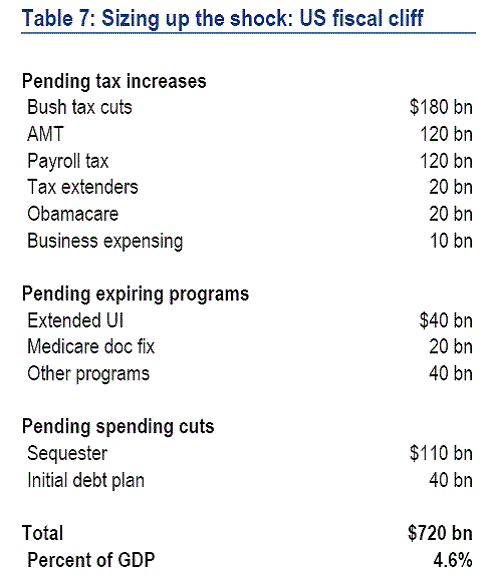

The “fiscal cliff” refers to a broad set of tax increases and spending cuts that under current U.S. law will take effect in January. A recent assessment by Bank of America Merrill Lynch estimates the tax increases in 2012 could come to $470 B and spending cuts another $250 B, for a combined fiscal shock of $720 B, or 4.6% of GDP.

Source: Bank of America Merrill Lynch

A fiscal contraction of this size in an economy as weak as the United States would likely be enough to send the country back into a recession. Since that’s not an outcome either party wants to see, my assumption has been that somehow Congress and the President will find a way to avoid it.

Some respected analysts have suggested to me that there is one political reason that our leaders might prefer to go over the cliff and then try to back our way up. The advantage is one of framing– once we’ve gone over the cliff, their position can be described relative to the new status quo, namely, every politician can claim to be in favor of tax cuts, but with the Democrats opposing “new tax cuts for the wealthy.”

If we were to drive over the cliff before trying to back up, one of the logistically cumbersome changes to undo involves the alternative minimum tax, since the changes here concern taxes owed on income earned in calendar year 2012. Business Week explains:

the number of households facing the alternative tax would increase to 32.9 million from 4.4 million, according to the Internal Revenue Service. That’s an average unanticipated tax increase of about $2,800.

The effect from the AMT, as the parallel tax is known, would be immediate in early 2013 because Congress hasn’t addressed the change for tax year 2012, and taxpayers start filing returns in January. A retroactive AMT change is much more cumbersome than retroactive changes in the 2013 income tax rates, which can be handled through paycheck-withholding adjustments, said Kenneth Kies, a Republican tax lobbyist in Washington.

Although discussions treat the “fiscal cliff” as a monolithic event, surely the outcome will be to break it up in pieces, with a likely consensus reached for another one-year extension of what Reuters describes as the “perennial patch” that exempts most Americans from the AMT. Indeed, Reuters reports:

the folks at Intuit Inc’s TurboTax unit are so sure the feds will eventually do that AMT patch, they are already programming their software as if it’s a done deal.

It should also be straightforward politically to reach a consensus on a one-year extension of the payroll tax cut. More complicated are the Bush tax cuts. Here’s a summary of what’s involved given by the Tax Foundation:

- The two “marriage penalty elimination” provisions will expire, so that:

- The standard deduction for married couples will fall, no longer double what it is for single filers; and

- The ceiling of the 15% bracket for married couples will fall, no longer double what it is for single filers

- The 10% tax bracket will expire, reverting to 15%

- The child tax credit will fall from $1,000 to $500

- The tax rate on long-term capital gains earned by middle- and upper-income people would rise from 15% to 20%

- The tax rate on qualified dividends earned by middle- and upper-income people would rise from 15% to ordinary wage tax rates

- The 25% tax rate would rise to 28%

- The 28% rate would rise to 31%

- The 33% rate would rise to 36%

- The 35% rate would rise to 39.6%

- The PEP and Pease provisions would be restored, rescinding from high-income people the value of some exemptions and deductions

The plan outlined in the Obama administration’s budget is to allow only one of those 12 provisions to revert exactly to what it was in early 2001:

- The top tax rate will revert from 35% to 39.6%

Then there are the automatic spending cuts set to take effect in January as a result of the Budget Control Act of 2012, which calls for a 9.4% cut in defense spending, 8.2% cuts in spending outside of defense and entitlements, and a 2% reduction in the amount health-care providers receive from Medicare– see the Center on Budget Policies and Priorities for details. In the third presidential debate, President Obama made the mysterious statement that

the sequester is not something that I’ve proposed. It is something that Congress has proposed. It will not happen.

What the President meant by that statement is unclear to many of us. But I would note that the “political framing” argument given above is a reason not to go over the cliff as far as the automatic spending cuts are concerned. Politicians on both sides will want to be on the record as voting for spending cuts, not increases, so finding a way to avoid the sequester, and later implement more modest versions of the cuts, might have some political advantages.

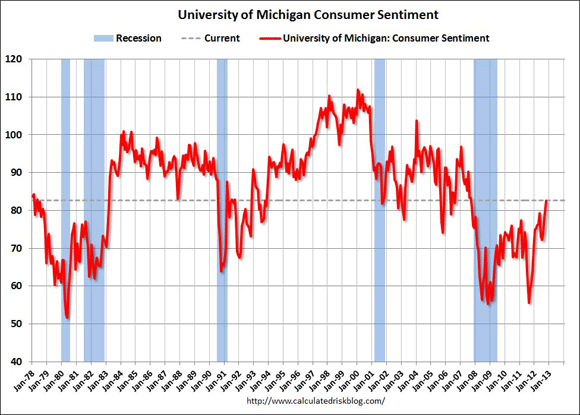

The most likely eventual outcome seems to me to be much more modest tax increases and spending cuts than implied by the full “fiscal cliff” scenario. A key question is then whether political brinksmanship, particularly the strategy of first going off the cliff before trying to find a way back up, could in and of itself exert significant costs. In my view the debt ceiling debacle last year did have a measurable effect on consumer sentiment and spending, though I don’t see any evidence of a replay of that so far in the most recent sentiment readings.

Source: Calculated Risk

On the other hand, businesses, particularly those with a tie to defense spending, may be more anxious, and it is possible that recent weakness in business fixed investment is related to concerns about what’s going to happen to federal spending and taxes. Moreover, the anticipated wrangling may have already locked in a decline in defense spending between 2012:Q3 and 2013:Q1.

It also is worth commenting on the dividend cliff. At the moment, the maximum tax rate on income from dividends is 15%. But under current law, in January we will see: (1) dividend earnings of high-income tax payers would come to be taxed at the regular income rate instead of the favored capital-gains rate, (2) the regular tax rate for upper-income households will rise from the current 35% to a new 39.6%; and (3) a 3.8% surtax will be added to dividend income of high-income investors. The combined effect of all three is that the maximum tax rate on dividends rises from a current value of 15% to a new value of 43.4%. That’s a sufficiently big change that I would not want to rule out the possibility of a significant effect on equity valuations or corporate governance.

Leave a Reply