Senator Shelby, Ranking Republican of the Banking Committee, has sponsored The Financial Regulatory Responsibility Act, which seeks to restrict implementation of Dodd-Frank, and require benefit-cost analysis for financial regulation. To quote Sen. Shelby: “”American job creators are under siege from the Dodd-Frank Act. “In their rush to expand the reach of government into our private markets, Congressional Democrats refused to consider the impact of the Dodd-Frank Act on economic growth or job creation.” [1] Now, it’s clear that British authorities have primary responsibility for regulating Libor (after all, the “L” in Libor stands for “London”). But I think it’s useful to consider this question because clearly similar concerns will arise in markets in the US sometime in the future.

Let’s move on, then. On Monday, July 16, in the wake of the Libor scandal, Senator Shelby responded to a question about Libor:

BARTIROMO: SENATOR, LET’S FACE IT. YOU ARE THE RANKING REPUBLICAN ON THIS SENATE BANKING COMMITTEE. I MEAN, ARE YOU MISSING ALL OF THIS? DAY IN AND DAY OUT? WHY MORE SCANDALS? EVERY TIME WE TURN AROUND HOW WILL WE GET CONFIDENCE BACK IF PEOPLE DON’T TRUST THE POLICEMAN AT THE — YOU KNOW, IN CHARGE.

SHELBY: WELL, THE POLICEMAN HAS TO BE DILIGENT. IF YOU REFER TO THE REGULATORS AS POLICEMEN WHICH THEY ARE, OF THE BANKING SYSTEM, FINANCIAL THING, THEY HAVE GOT TO BE INVOLVED. THEY CAN’T JUST HAVE SOME INFORMATION SOMETHING IS GOING WRONG AND QUIT AND KICK IT DOWN THE ROAD AND HOPE IT NEVER COMES UP AGAIN. THAT’S BASICALLY WHAT HAPPENED AS FAR AS WE KNOW IT THIS TIME. THEY HAVE GOT TO BE DILIGENT. THEY’VE GOT TO SAY GOSH WE HAVE TO INTEGRITY ABOVE EVERYRTHING IN OUR BANKING SYSTEM. WE USED TO HAVE IT. WE NEED TO GET THERE AGAIN.

An observation: If the regulators are constantly criticized for implementing regulations (see Senator Shelby’s comments on CFPB [2]), they are unlikely to vigorously pursue violations. However, the question at hand is whether the proposed legislation would have allowed intervention/regulation. To answer that, we need assess the costs of the Libor manipulation. Morgan Stanley has provided some back of the envelope calculations. From FT Alphaville (h/t Naked Capitalism/Yves Smith):

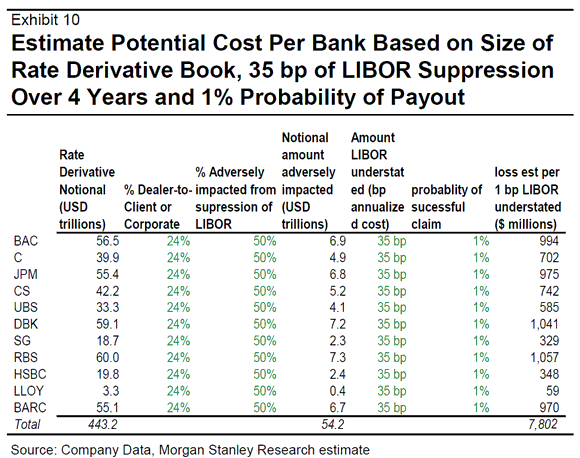

Exhibit 10 from Morgan Stanley via FT Alphaville.

So, as Yves Smith summarizes:

$350 trillion net notional x 25% customer trades x 33% net loss incidence from manipulation x 1 basis point revenue capture

That gives you $2.9 billion across all 16 banks, or $180 million per bank. Times four years, you have $720 million. Compensation as a percent of investment bank revenues is typically 40% to 50%. So we have, on pretty conservative assumptions, roughly $290 to $360 million in extra comp on average per bank for Libor manipulation. This would presumably have gone to comparatively few people (recall Bob Diamond trying to say only 14 traders were involved, although the FSA said “at least 14″). Assume 20 per desk. plus everyone in the reporting line above would have benefitted, as well as the C level execs. So how many people is that? Maybe 50 tops? OK, let’s be really charitable and assume only 50% directly benefitted those people, the rest helped improve bank-wide comp (all those back office types, etc). Even assuming that, you have an average of $2.9 to $3.6 million in extra bonuses per person over the four year period.

The point here is pretty simple. Even if you go to some lengths to cut the numbers way down, you come to the conclusion that if this manipulation had any meaningful impact on the profits of the swaps and derivatives desks, a comparatively small number of people who’d be very cognizant of the manipulation by virtue of seeing the contrast between posted Libor versus actual market prices, likely profited very handsomely. And the people up the line would have benefitted as well.

So we have a guess, after the fact, about the costs. And yet I am confident that regulation of Libor will be resisted, even as outrage is voiced about manipulation, because that will cut into rents.

Since the violations occurred in London, it might not be the same groups that call for regulation but I’m guessing the same arguments will arise, as were levied in 2010. As Jeffry Frieden and I wrote in Lost Decades (p. 165) about the modest attempts to regulate finance, such as in Dodd-Frank:

Not everyone agreed with the regulatory changes adopted in 2010. Some felt they went too far in imposing restrictions on the private sector. One group of conservative leaders argued against the Dodd-Frank legislation on the grounds that it “would increase the size and scope of the federal government, regulating every phase of economic activity.” For them the proposal was another misguided attempt to overregulate businesses. “Due to the bill’s excessive taxes and government red tape,” they argued, “families and small business owners would no longer have access to low cost credit, and a bureaucrat would stand between them and living the American dream.”38 Conservative activist Grover Norquist charged that the reform put in place “costly and colossal new regulations . . . burdens banks with billions of dollars in new fees and restrictions . . . creates a massive new government agency with the power to monitor virtually any American citizen’s or business’s bank accounts.”39

In other words, as long as finance captures legislators and regulators, “light touch regulation” (which I gather approximates Senator Shelby’s view of optimal regulation) will be favored, and excess returns will flow to the financial sector, because the costs are easy to see, but the benefits hard to discern, ex ante.

One final point: It might have been the case that during the height of the financial crisis, there was an incentive for regulators to look away, as lower Libor kept interest rates low elsewhere in the system. [3] (In fact, it was pretty well known that Libor was not representative of borrowing costs at the peak of the TED spread.) But for the rest of the time, it is unclear to me that allowing a financial price to be distorted enhances the efficiency of the system. In other words, I believe that government intervention is sometimes necessary in the midst of a full-blown crisis. But the under-quoting of offer rates for the entire past five years clearly does not fall under that category.

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply