Any post about value investing always evokes strong responses, but I thought I would start this one by turning the focus inwards. So, here are a few questions for you :

1. Would you classify yourself as a “value investor”?

a. Yes

b. No

2. If yes, what makes you a value investor?

a. I try to estimate the value of a stock before I invest in it

b. I only buy stocks that trade at attractive multiples (low PE, low PBV etc.)

c. I do my homework, looking at the fundamentals, before I invest

d. I don’t know. I just am.

3. Finally, do you think that value investors collectively do better than other investors in the market?

a. Yes

b. No

c. Not Sure

If yes, what is the source of their advantage? If not, why do you think they fail?

- On the first question, I would not be surprised if the preponderance of visitor to this site classify themselves as value investors. After all, value investing has become so broadly defined that everyone seems to be in this camp, and when everyone is a value investor, no one is a value investor. For value investing to work as an investment philosophy, it needs foils, preferably in the form of investors who know little about fundamentals and care about them even less. Paraphrasing Warren Buffett, if investing is a game of poker and value investors are the card counters, you need suckers at the table who will supply the winnings.

- On the second question, as value investing has expanded well beyond the Ben Graham school of strict (and passive) value investing to include different and seemingly contradictory strands of investing, there is less consensus about what comprises a good “value” stock. In a recent paper on value investing (which, in turn, is closely modeled on a chapter in my book on investment philosophies), I presented my take on these issues.

- On the third question, it does seem to be taken for granted, at least in the value investing community, that value investors are not only more virtuous than other, more fickle investors (growth investors, momentum investors) but that their “hard work” pays off in the form of higher returns, at least over long periods. It would be vindication of the “ant and the grasshopper” fable, if it were true, but is it?

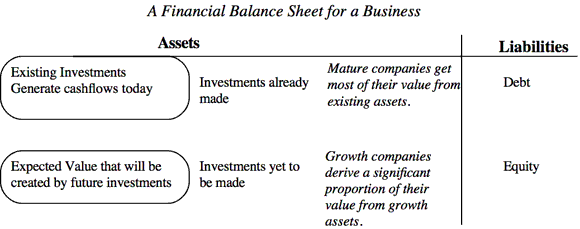

What is the key characteristic that separates value investors from the rest of the world? In my view of the world, and I understand that yours might be different, the key to understanding value investing comes from breaking down a business into assets in place and growth assets.

It is this mechanism that I used to my posts on estimating how much you are paying for growth and how much that growth is worth. If you are a value investor, you make your investment judgments, based upon the value of assets in place and consider growth assets to be speculative and inherently an unreliable basis for investing. Put bluntly, if you are a value investor, you want to buy a business only if it trades at less than the value of the assets in place and view growth, if it happens, as icing on the cake.

It is how you find investments that sell for less than the value of assets in place that provides a framework to understanding the different strands of value investing, and there are three ways you can go about this mission:

a. Passive value investing: The oldest strand of value investing traces its lineage back to Ben Graham and his use of screens to find cheap stocks. Reviewing those screens, which combine market and accounting data, from Graham’s book on security analysis, you are looking at stocks that trade at low multiples of earnings, pay a high proportion of these earnings as dividends and have a high proportion of assets that can be liquidated for close to their book value. In the years since, investors have added other screens (good management, stable earnings, strong competitive advantages etc.) that are all designed to reduce the potential for downside on the investment.

b. Contrarian value investing: In contrarian value investing, you adopt a different tack. You look for companies whose stock prices have collapsed for one reason on another. In its least sophisticated variant, you just buy the biggest losers (at least in terms of stock price), on the assumption that markets generally over react and that the portfolio of these losers will bounce back over time. In its more refined forms, you add other criteria to the mix. Thus, you may buy stocks that have gone down but only if they have a strong brand name and/or little debt.

c. Activist value investing: In activist value investing, you focus on poorly performing companies and look at the value of its assets in place, with better management in place. You then try to change the way the company is run by either acquiring control of the firm or putting pressure on existing management. Activist investing requires far more resources than either passive or contrarian value investing.

The skills and strengths you need to succeed in each of these value investing approaches is different and it is not clear than an investor who succeeds using one strand of value investing will be comfortable with the others. In the next three posts, I will focus on each of these strands of value investing. In the last post, I will examine the most contentious issue of all, which is whether value investors collectively generate value from their efforts or whether this too is “fool’s gold”.

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply