The global economy appears to be headed over cliff this year. The emerging world is experiencing a significant economic slow down, the Eurozone will probably break apart in the next few months, and the United States faces sharp austerity measures at the end of the year. There are enough bearish developments here to make the original Mayan calendar look prescient after all. So should we despair? Is the global economy fated to collapse in 2012?

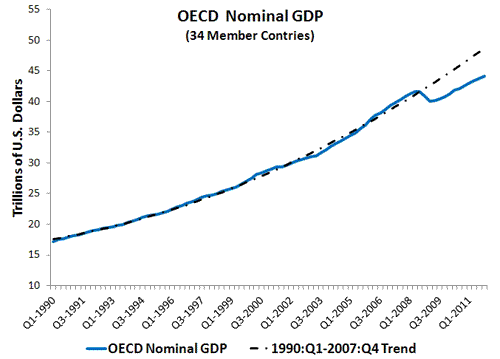

No, says Willem Buiter and Ebrahim Rahbari of Citigroup. Though the outlook is dire, they argue there is much more the Fed, the ECB, the Bank of Japan, and the Bank of England could do not only to prevent another global economic collapse this year, but also to spur global aggregate demand above its anemic levels as seen below:

Source: OECD Statistics

So what does Buiter and Rahbari recommend? Via FT Alphaville, here are their recommendations:

(i) reducing rates, first by lowering them all the way to zero (UK and euro area), then by eliminating the effective lower bound on nominal interest rates (all four currency areas)

(ii) carrying out more imaginative forms of quantitative easing (QE) & credit easing (CE), in all four currency areas, by focusing on outright purchases of and/or loans secured against less liquid and higher credit risk securities, subject to a sovereign guarantee (joint and several in the euro area) for all such risky central bank exposures

(iii) engaging in helicopter money drops (all four currency areas): a combined fiscal monetary stimulus

The authors say the best of these options is (ii) and (iii). These are radical proposals that would require both monetary and fiscal collaboration, but right now radical solutions are exactly what the world needs. The global economy needs a jarring slap to the face to awaken it from its heightened risk-averse stupor. These proposals would most likely do it, but they lack an endgame. How much imaginative QE and helicopter drop money should be done? This is an important question, because without an endgame to drive market expectations, these measures will be less effective and have the potential to unmoor long-run inflation expectations. And, as Kelly Evan notes, monetary authorities are loathe to simply try something without some guiding objective.

Enter a nominal GDP (NGDP) level target. It would provide an explicit endgame for the policymakers as they implemented these imaginative QE and helicopter drops. This would not only keep inflation expectations anchored, but would create the incentives for investors across the globe to do much of the heavy lifting required to restore robust global aggregate demand growth. For example, imagine that monetary authorities in the United States, Europe, United Kingdom, and Japan simultaneously announced they were going to engage in as much imaginative QE and helicopter drops necessary to restore NGDP to some pre-crisis trend. How do you think markets would respond to these announcements? It is highly likely that the mother-of-all portfolio adjustments would take place, with investors across the glove moving into riskier, higher-yielding assets in anticipation of higher aggregate nominal spending. This would raise asset prices, lower risk premiums, and create a self-sustaining recovery. It really is not that hard.

So no, the global economy is noted fated to a Mayan calendar-type collapse. Policymakers can make a huge difference this year and do so in a systematic, stabilizing manner. The question is whether policy makers will act in time. Ambrose Evans-Pritchard is not sure they will:

[S]overeign central banks have the means to defeat any depression thrown at them by launching mass purchases of assets outside the banking system, working through the classic Hawtrey-Cassel quantity of money mechanism until nominal GDP is restored to its trend line.The problem is not scientific. A world slump is preventable if leaders act with enough panache. The hindrance is that the Euro Tower still haunted by Hayekians, and most G10 citizens – and Telegraph readers from my painful experience – view such notions as Weimar debauchery, or plain Devil worship. Economists cannot command a democratic consent for monetary stimulus any more easily today than in 1932.

I hope policymakers prove him wrong.

Leave a Reply