The European unemployment numbers are out. The story from the Financial Times:

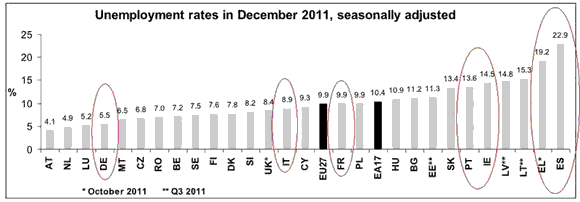

Unemployment in the 17 euro countries climbed to 10.4 per cent in December, with the November rate revised upwards to the same rate, setting a fresh record since the introduction of the single currency in 1999. So-called “peripheral” members such as Spain and Greece recorded the highest rates, of 22.9 per cent and 19.2 per cent respectively.

By contrast, national data from Germany, the eurozone’s bulwark, showed joblessness declined in January to 6.7 per cent, the lowest level since reunification in 1991.

And a picture is worth a thousand words:

Perhaps France and Italy can hang on while relative wage deflation increases competitiveness with Germany, but conditions in the periphery look downright dire. And note that years of austerity have done little to help Greece and Ireland. I don’t see the same medicine working in Spain or Portugal either. It is no wonder that Greece is looking for very substantial reductions in its debt, and it seems inevitable that Portugal will come to the same conclusion sooner or later. The great disparity in unemployment rates is another factor that leaves me pessimistic on the ultimate outcome of the Euro experiment. We need real fiscal transfers, and soon. More carrot with stick.

For now, however, market participants are focused on the salutary effects of the ECB’s LRTO (not to mention expectations for another round of QE from the Fed). Have these efforts eased conditions enough to allow for a Portuguese restructuring or even Greece’s exit from the Euro? Or have market participants and European policymakers been drawn into a dangerous path of complacency? Thinking aloud, do current market conditions embolden German politicians to think they can finally cut Greece loose with little or no consequences to the rest of Europe? Would this indeed be the case? I have trouble believing in the “orderly exit” story, but perhaps the can has been kicked far enough down the road that it can happen.

Leave a Reply