In 1960 Hayek wrote an essay titled “Why I Am Not a Conservative.” In it, Hayek pondered the conundrum that many Americans like me have struggled with since: What should we call ourselves? This is not a problem in Europe: I would be a liberal. Adam Smith is the quintessential liberal, in the European sense. But as Schumpeter noted, in the US, those who supported big government and wanted to limit and control the free market started calling themselves liberal: ”[a]s a supreme, if unintended, compliment, the enemies of private enterprise have thought it wise to appropriate its label.” So unhyphenated liberal means “progressive” or the like in the US, and that is definitely not an accurate label for a believer in a minimal state. Say “classical liberal” in the US and people just hear “liberal” and think “progressive”: confusion still reigns. ”Conservatives” in the European sense, as Hayek argued, are primarily traditionalists, and hostile to many economic, personal, and civil liberties.

So what is the alternative? By default, “libertarian”–a word that Hayek said “[f]or my taste . . . carries too much the flavor of a manufactured term and of a substitute”–is pretty much all that is left. Again quoting Hayek: “But I have racked my brain unsuccessfully to find a descriptive term which commends itself.” So libertarian has pretty much become the default term to describe someone in the US who is not a liberal/progressive, traditional conservative, socialist, communist, or what have you.

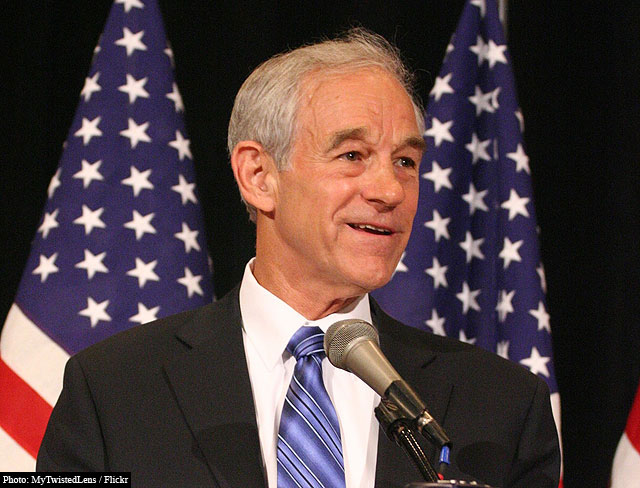

But the “libertarian” label has been claimed by myriad people whom Hayek, and Friedman, and Richard Epstein–and Adam Smith–would find repulsive and decidedly unliberal, in the classical sense. The most prominent of these today is presidential candidate Ron Paul. Another is Paul’s former chief of staff Lew Rockwell. Yet another is radio ranter Alex Jones. (Sort of working my way down the food chain here.)

As Paul has made a serious challenge in Iowa, he and these others, and his supporters, have attracted much more scrutiny. And what is revealed is not pretty. Actually, ugly would be the proper word.

Many have documented the ugliness–most notably the racism that pervades Ron Paul’s newsletters from the 90s. A good compendium can be found at Ace of Spades. Given all that’s out there, I’ll let you find it for yourself. Just be prepared for what you find. Don’t say you weren’t warned.

I just want to make a few points.

First, much of the most trenchant criticism of Paul and his cultish followers (more on them later) comes from people who are sympathetic with many of the position he takes. These critics think that government is far too large, and that our liberties have been progressively (pun intended) eroded. And I agree.

But the dislike of Paul and the Paulians for the government has curdled into a hatred of America. There is no ugly anti-American conspiracy theory that they do not embrace. 9-11 Trutherism, for instance. They routinely recycle theories first floated by the KGB. No wonder RT loves Paul and gives Rockwell plenty of air time. And it is this profound anti-Americanism that repels people like me, and other Paul critics–people who believe that America is flawed but the last, best hope of mankind that has on balance been a profound force for good at home and in the world at large.

Second, Paul and the Paulians are utterly unrealistic in their prescriptions. Politics is the art of the possible, but Paul advances impossible plans built on fantastical foundations. Maybe a dictator could implement them. Maybe. But even ignoring the irony of dictatorial libertarianism, these grandiose plans are fundamentally at odds with Hayek’s warnings about the pretense of knowledge: the unintended consequences of libertarian social engineering would likely be as traumatic, at least in the short run, as socialist social engineering. The world is not an Etch-a-Sketch that you can shake clear and start all over again. But Paul evidently thinks so and prescribes root-and-branch transformations of every aspect of government policy from money to the military.

And the shrieking vituperation that Paulians direct at those who point out these realities makes plain that if, heaven forfend, they did take power they would be as extreme and uncompromising as any True Believing Bolshevik or Khmer Rouge. Disagree with any of their extremely unrealistic prescriptions–abolish the Fed, adopt the gold standard, eliminate every American overseas military facility–and you will be immediately bombarded with the Paulian insult trilogy: “neocon, statist, warmonger.” Yeah, that’s the way to win friends and influence people.

Paul’s historical disquisitions present a revealing perspective on his belief in his unique ability to find magical solutions to immense problems in the face of political obstacles that stymied generations of able statesmen in the past. The Civil War is an excellent example. He has called Lincoln a warmonger, and claims that the Civil War could have been avoided at lower cost by buying slaves.

Yeah. Nobody thought of that. Gee, I wonder what the problems would have been? Like: who would pay? Would the South have agreed to a paid emancipation plan given that the primary source of government revenue was tariffs that were paid largely out of Southern agricultural exports, notably cotton (an import tax is equivalent to an export tax)? Would Northerners, who were not, truth be told, abolitionists, been willing to pay taxes to compensate rich Southerners to free blacks whom most Northerners didn’t care a whit about? And another issue: as Reconstruction demonstrated, the issue of slavery was more complicated than dollars and cents. It involved the entire social structure of the South. One could go on.

Lincoln was in fact sympathetic to the idea of paid emancipation: he advanced the futile plan of buying slaves and relocating them to Africa. It was a political and practical folly.

But pay no mind to these practical realities. Ron Paul would have solved the political problem that bedeviled America from its founding. It is an American tragedy that Ron Paul was not around at the beginning of the 19th century. (Well, maybe he was. He is pretty old.)

Paul’s and the Paulian’s treatment of political issues past and present reveals them to be political gnostics of the radical dualist stripe. They believe they have special esoteric knowledge that gives them the ability to devise schemes of social salvation. They believe that the political world is divided between powers of darkness and powers of light.

These positions are utterly fantastical and have no hope of prevailing. Moreover, the stridency, weirdness and frequent ugliness of the advocates of these positions actually undermine the prospects for progress towards a smaller, Smithian state that focuses on protecting people against force and fraud. In 2012, Paul empowers Obama. Paul has no chance of winning, but he can so damage the already tenuous Republican presidential prospects that Obama could coast to victory despite fundamentals that would doom him to a landslide loss in most years.

But even beyond 2012, Paul and Paulians have so tarnished the libertarian label, that many like me are revisiting Hayek’s question: what’s my name again? And further: what is the practical political program that will lead to a smaller, less intrusive, less controlling, less destructive state? That is what Hayek pondered. That is what Friedman wrote about. That is what serious Smithian liberals think about today. That is not what Ron Paul and the Paulians do. And what they do gives libertarianism a bad name.

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply