In addition to testifying before Congress, Federal Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke today tried to explain the Fed’s plans and options directly to the public through an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal. Here I provide some background on what Bernanke’s talking about in terms of an “exit strategy” for the Fed, and offer some thoughts on his remarks.

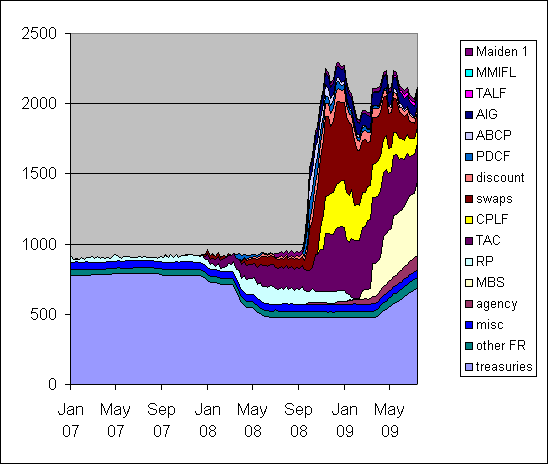

The basic power of the Fed derives from its ability to create money, which it can use to buy assets or extend loans. We can summarize the Fed’s actions in terms of either the asset side of its balance sheet (the assets and loans it holds), or the liabilities side (the money or other obligations it has created). Let’s start with the asset side. Up until January of 2008, by far the most important assets held by the Fed were short-term Treasury bills. As last year wore on, the Fed significantly expanded its loans in the form of currency swaps with foreign central banks, direct lending to U.S. banks through term auction credit, and the Commercial Paper Lending Facility. Altogether such measures more than doubled the various asset holdings of the Fed by the end of the year, despite the fact that the Fed sold off 40% of its original T-bills.

Figure 1. Factors supplying reserve funds, in billions of dollars, seasonally unadjusted, from Jan 1, 2007 to July 15, 2009. Wednesday values, from Federal Reserve H41 release. Agency: federal agency debt securities held outright; swaps: central bank liquidity swaps; Maiden 1: net portfolio holdings of Maiden Lane LLC; MMIFL: net portfolio holdings of LLCs funded through the Money Market Investor Funding Facility; MBS: mortgage-backed securities held outright; CPLF: net portfolio holdings of LLCs funded through the Commercial Paper Funding Facility; TALF: loans extended through Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility; AIG: sum of credit extended to American International Group, Inc. plus net portfolio holdings of Maiden Lane II and III; ABCP: loans extended to Asset-Backed Commercial Paper Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility; PDCF: loans extended to primary dealer and other broker-dealer credit; discount: sum of primary credit, secondary credit, and seasonal credit; TAC: term auction credit; RP: repurchase agreements; misc: sum of float, gold stock, special drawing rights certificate account, and Treasury currency outstanding; other FR: Other Federal Reserve assets; treasuries: U.S. Treasury securities held outright.

In 2009, the Fed has been winding down some of these programs, with significant declines in swaps, CPLF, and TAC, replaced by big increases in items such as mortgage-backed securities and agency debt. The changes over the last few months should not by any stretch be described as a return to “plain vanilla” central banking. The risk on MBS and agencies is greater than that for T-bills, and the asset level today remains 130% above its value at the start of 2007.

Where did the Fed obtain the funds with which it acquired all these new assets? To say that it did so by “printing money” would be inaccurate. The Fed doesn’t lend a half trillion in term auction credit by handing out big bundles of green paper with Ben Franklin’s picture on them. Instead, it creates an entry in an account that the recipient bank has with the Fed known as the bank’s Federal Reserve deposits. The bank could, if it wanted, use those credits to ask the Fed for those Ben Franklin souvenirs. Instead the bank presumably used the new deposits to pay for some obligations or make some loans, either of which it would instruct the Fed to implement by transferring those reserves to some other bank. That bank in turn could use the reserves to ask for C-notes, or pass them on to somebody else through its own loans or any other expenditures.

And the buck stops– where? In normal times, the process of banks putting any excess reserves to use would continue until there’s enough expansion of banking and economic activity that ultimate recipients did want to turn those reserves into green currency. And once that happens, it would not be a misleading summary of the bottom line to say that the Fed eventually paid for its original asset purchase by “printing money”.

But in the fall of 2008, the Fed did not want that to happen. It wanted to extend a trillion in new loans, but it did not want to see currency held by the public go up by a trillion dollars, out of fear the latter would be very inflationary. The Fed’s thinking was that we didn’t need a traditional inflationary expansion of credit, but instead needed to allocate credit to particular functions without having conventional measures of the money supply swell.

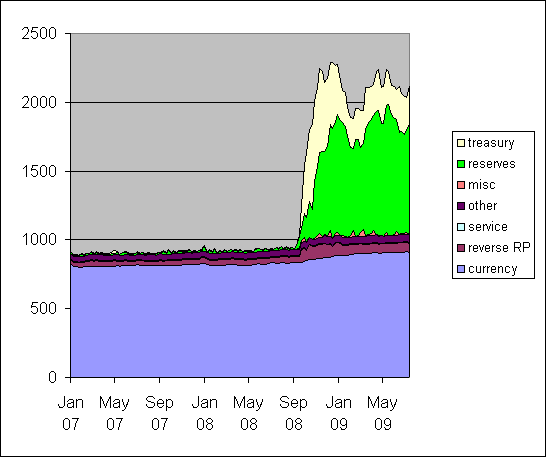

The graph below describes how the Fed did that, looking now at the liabilities side of the Fed’s balance sheet. The height of Figure 2 at any date is identical, by definition, to the height of Figure 1, but whereas Figure 1 was looking at what the Fed did with its funds, Figure 2 summarizes how the Fed obtained those funds. In other words, Figure 2 looks at where the reserve deposits the Fed created ended up, and explains why the dramatic actions of Figure 1 haven’t yet shown up as currency held by the public.

Figure 2. Factors absorbing reserve funds, in billions of dollars, seasonally unadjusted, from Jan 1, 2007 to July 15, 2009. Wednesday values, from Federal Reserve H41 release. Treasury: sum of U.S. Treasury general and supplementary funding accounts; reserves: reserve balances with Federal Reserve Banks; misc: sum of Treasury cash holdings, foreign official accounts, and other deposits; other: other liabilities and capital; service: sum of required clearing balance and adjustments to compensate for float; reverse RP: reverse repurchase agreements; Currency: currency in circulation.

One big factor has been the accounts that the U.S. Treasury holds with the Fed. Essentially, the Fed asked the Treasury to borrow some money through public auctions, which it did. Banks paid for these new T-bills by instructing the Fed to transfer to the Treasury the Federal Reserve deposits that they’d received from the Fed as a result of the programs in Figure 1. The Treasury then just left the funds sitting there in its accounts with the Fed. In effect, the Fed obtained the funds for some of its actions on the asset side not by “printing money” but instead by having the Treasury borrow funds on its behalf on the liabilities side.

However, an even bigger volume of the deposits that the Fed created are still just sitting on the banks’ books. The way the fed funds market functioned in 2007, that would never have happened. Why close your bank’s books for the day with funds just sitting there in an account with the Fed, earning no interest, when you could loan them out overnight instead? A big bank would never do such a thing in 2007. But they’re happy to do so in 2009, in part because the overnight lending opportunities are not particularly attractive at the moment, and in part because the Fed now pays interest on those reserves. From the bank’s point of view, funds left on deposit with the Fed at the end of the day aren’t idle at all, under the new system adopted in the fall of 2008.

One of the points that Bernanke makes in his op-ed is that the Fed could continue to use this device, if need be, to prevent essentially any volume of its asset side activity from showing up as an increase in currency held by the public, simply by raising the interest rate the Fed offers to pay on reserves to whatever level is necessary to persuade banks to continue to hold these funds idle overnight. In effect, the Fed is through this device borrowing directly from the public to fund its asset-side activities rather than by “printing money”.

Should that allay any inflationary concerns people may have about the doubling in the size of the Fed’s balance sheet? In a narrow mechanical sense, perhaps. It is true that the new assets have not yet shown up as an increase in the money supply, and it is true that the Fed has the power to prevent them from doing so in the future. But my concerns about inflation are not that the Fed would lose the ability to target a particular level for the money supply, and certainly are not concerns about the next six months, where I still see deflation as a bigger worry than inflation. Instead, my concern is that the current fiscal trajectory is fundamentally inconsistent with the Federal Reserve choosing to keep inflation under control. Both devices, ballooning of the Treasury’s account with the Fed and enabling the Fed in effect to borrow directly on its own, are indeed as much fiscal measures as they are monetary. But to someone worried about the increasing co-mingling of monetary and fiscal policy, that blurring of the lines is not a reassuring development.

My specific worry is that we will eventually face a crisis of confidence in the Treasury and the dollar itself. It is true, as Bernanke suggests, that raising the interest rate paid on reserves in such a setting would be a policy tool that could be used in response. But it would be an unattractive measure to the point of perhaps being impossible to use in practice, for the same reason other countries have dreaded raising interest rates in the face of collapsing real economic activity and a flight from their currency.

I fear that the United States government is mistakenly assuming that it can borrow essentially unlimited sums without undermining confidence in the dollar itself. The real question of a successful exit strategy, in my opinion, is how do we extricate ourselves from the joint fiscal commitments currently assumed by the Treasury, the Fed, the FDIC, the Medicare and Social Security trust funds, and various and sundry implicit and explicit federal guarantees?

The answer, in my opinion, is not to be found in the Treasury doing even more borrowing on behalf of the Fed or the Fed doing even more borrowing on behalf of itself.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply