It seems that the ECB’s policy prescriptions are being guided more by ideology and moral judgment than by sound economics. A very revealing letter from the ECB to the Italian government from August has just been published in the Italian press. The BBC reports:

ECB told Italy to make budget cuts

The European Central Bank told Italy to make sweeping changes to its labour laws and take tough action to cut the deficit, a leaked letter has shown. In the letter, sent to prime minister Silvio Berlusconi in August, the ECB said the severity of Italy’s economic situation made “bold and immediate” action “essential”.

…In unusually clear language, the signatories told Mr Berlusconi to make deep reforms, including opening up public services and overhauling pay bargaining and hiring and firing rules.

…The letter, published in Corriere della Sera, said Italy should aim to bring the deficit down to 1% of gross domestic product by 2012 and balance the budget by 2013, a year ahead of schedule, “mainly via expenditure cuts”.

This is troubling in several ways. First, as the article points out, the timing of things certainly makes it appear as if there was a quid pro quo: the ECB would help only if the Italian government took certain policy steps that the ECB wanted. The ECB has continuously denied that there was any such condition attached to ECB assistance, however — which is a relief, because otherwise this would look awfully like an instance where a central bank was blackmailing a democratically elected government.

Second, the ECB was apparently expressing a purely ideological preference for Italy to reduce its budget deficit through spending cuts. But shouldn’t the size of a country’s government, and decisions about whether to use tax increases or spending cuts to reduce a deficit, be determined by the country’s democratic process? When Alan Greenspan disguised his opinion that the US budget deficit should be primarily reduced through spending cuts rather than tax increases as the official advice of the Federal Reserve back in 2005, many (including me) where dismayed by this conflation of economic policy advice with ideological preference. (Bernanke has done a much better job of keeping those two separate, by contrast.) So it’s disturbing to find the ECB leadership now directly trying to impose its own apparent small-government inclination on democracies in the eurozone.

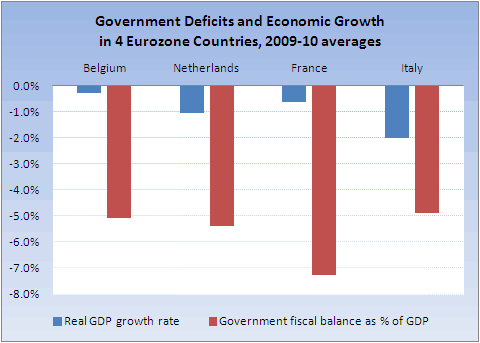

But third and most distressing to me is how a central element of the policy prescription that the ECB made to Italy was completely wrong. Italy’s problem is not annual budget deficits; yes, Italy had chronically large budget deficits during the decades leading up to euro adoption in 1999, but Italy actually ran smaller budget deficits than France, Belgium, or even the Netherlands over the past couple of years (see chart below).

Italy’s problem right now is low growth, and the fact that such low growth makes it more difficult for Italy to service the massive debt is has left over from 20 or 30 years ago. The recession hit Italy very hard, and the country has been slow to recover (which makes Italy’s relatively low budget deficits even more impressive, by the way). The last thing Italy needs at this point is a sharp fiscal contraction.

So why would the ECB have asked Italy’s government to apply contractionary policy when Italy is struggling to emerge from a very deep recession? Why would they point the finger at Italy’s budget deficits as the problem, when Italy has been better than many of the core euro countries at keeping them under control? The economics of this policy advice is all wrong.

I fear that this is yet another sign of how the eurozone crisis has undammed a reservoir of cultural and moral judgment of southern Europe by some in the north. The north-south cultural divide in Europe has always been significant, but it was easy to overlook it during the prosperous years leading up to the recession of 2008. Now, it seems, all of those old prejudices are coming out again, and a surprisingly large number of people are falling back on the simplistic sterotypes that southern Europeans are lazy and irresponsible, have jeapordized the euro through their moral failings, and need to be given a punishingly large dose of austerity – whether it makes economic sense or not. Unfortunately, it’s beginning to seem like some at the ECB agree.

Leave a Reply