The U.S. labor market is bad shape. The great recession and its aftermath are the chief culprits, of course, but the sputtering began earlier. In the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s employment increased so rapidly that our economy was sometimes referred to as the “great American jobs machine.” In the early and mid 2000s that ended.

Richard Freeman and William Rodgers were among the first to draw attention to the shift. In 2005, well into the recovery following the 2001 recession, they noted the anemic job growth relative to prior recoveries and wondered if the labor market had changed fundamentally.

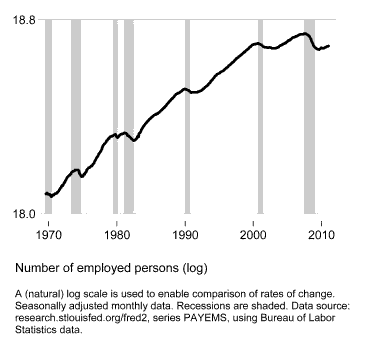

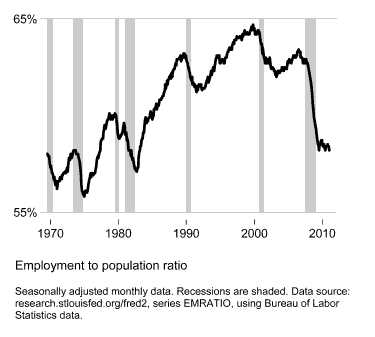

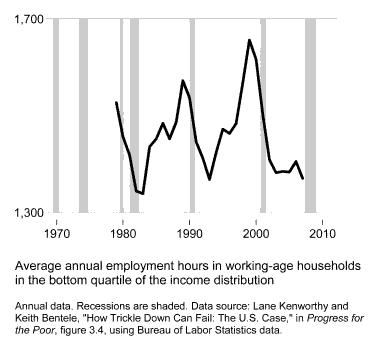

Here are some revealing indicators.

During the growth phase of the business cycle, from 2002 to 2007, the number of people employed increased less rapidly than in previous upturns.

The employment-to-population ratio gained no ground over the 2002-07 upturn. It was 63% when the economy emerged from recession at the beginning of 2002 and 63% just before it plunged back into recession at the end of 2007.

Rising employment is particularly important for those at the low end of the labor market. Here too the 2000s upturn was a disappointment. In working-age households in the bottom quartile of the income distribution, average employment hours failed to rise at all.

What caused this collapse of the American jobs machine? I think the most convincing explanation is a shift in management’s incentives and in its leverage relative to employees. According to Robert Gordon, this has its origins in the 1980s and 1990s but emerged in full force in the early 2000s:

Business firms began to increase their emphasis on maximizing shareholder value, in part because of a shift in executive compensation toward stock options. The overall shift in structural responses in the labor market after 1986 were caused by … the role of the stock market in boosting compensation at the top, … the declining minimum wage, the decline of unionization, the increase of imported goods, and the increased immigration of unskilled labor. Taken together these factors have boosted incomes at the top and have increased managerial power, while undermining the power of the increasingly disposable workers in the bottom 90 percent of the income distribution.

Executives’ compensation is heavily influenced by their firm’s stock price. Financial advisers believe “lean and mean” delivers better long-term corporate gains. Employees have limited capacity to resist employment cutbacks during hard times and to press for more jobs during good times.

During the 2000s upturn this made for sluggish employment growth despite conditions that were, in historical and comparative terms, quite favorable for hiring: buoyant consumer demand, low interest rates, limited labor market regulations, modest wages and payroll taxes.

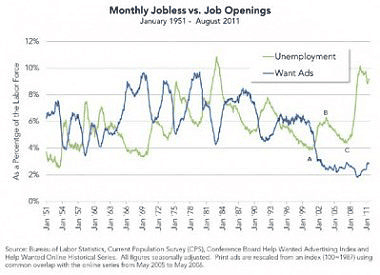

Is there direct evidence that employers were reluctant to hire? The pattern in the following chart, from Scott Winship, is telling. In the 2001 recession, posted job openings as a share of the labor force (the blue line in the graph) fell to their lowest level in more than half a century. Then, as the economy picked up steam, posted openings didn’t budge. The lack of increase was a sharp departure from previous upturns.

Many hope that when the economy finally gets moving again, we’ll return to the glory days of rapid employment growth. But developments in the 2000s, prior to the crisis, paint a discouraging picture.

The importance of this slowdown in employment growth is hard to overstate. In recent decades the American labor market has suffered from twin maladies: it’s been producing fewer middle-paying jobs and wages in the bottom half of the earnings distribution have been stagnant. For much of this period its chief virtue was that it created a large number of jobs. That looks to have gone by the wayside.

Leave a Reply