The August unemployment rate was 9.1 percent. Not much joy in Mudville.

About one in five Americans in the prime age for working range remain under-employed.

We have the short-run problem related to economic growth and the fact that families, businesses, and governments need to get their balance sheets in order before they will really begin to spend again.

We have the long-run structural problems in the labor market related to the fact that the skills of many individuals of working age do not mesh with the jobs the economy is creating or is going to create. For a dismal picture of this situation see the recent article in Bloomberg Businessweek (August 29—September 4, 2011) titled “The Slow Disappearance of the American Working Man.”

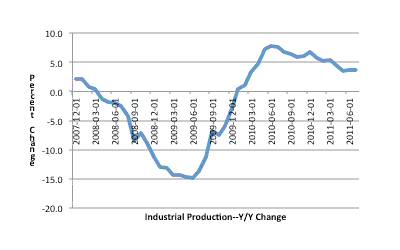

And short-run growth seems to be going nowhere. Just look at the year-over-year rate of change in industrial production. Note that this series peaked in the second quarter of 2010. The modest decline in this growth rate has now been going down-hill for more than 12 months.

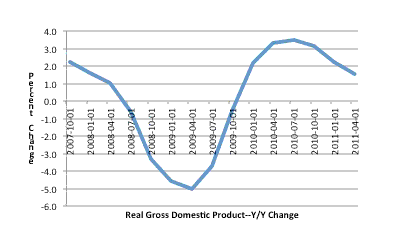

Of course, the performance of industrial production is also captured in the year-over-year growth rate of real Gross Domestic Product. Here the peak growth rate was achieved in the third quarter of 2010. The growth rate has declined since.

If the economy fails to grow by 3.0 percent or more, jobs will not be added at a rate that will lower the unemployment rate. And, growth at this rate will certainly not resolve the long run problem related to those that are holding part-time positions that would like to have full-time jobs and those people that have left the work force.

Furthermore, this scenario is not one that is favorable to people making much headway in reducing the burden of their debts. Thus, the “debt overhang” seems to be a part of the continuing saga of our economic malaise. The environment for getting out of debt does not exist.

Given this picture, the questions that arise pertain to the concern that America may face a decade like Japan has faced or a decade like that in America in the 1930s. Maybe this is the “payback” for the period of credit inflation we have experienced over the past fifty years. Maybe the only way out of this situation, which is not a short-run solution, is to focus on the fundamentals, focus on the structural problems created over the past fifty years.

The Federal Reserve, so far, has acted so as to prevent another “shock” to the economy like the one they introduced in the 1937-38 period. In this earlier period the Fed caused banks to become even more restrictive in their lending operations than they had been and this precipitated a second depression for the 1930s. This time the Fed has flooded the banking system with liquidity and seems to be in no hurry to remove anything that appears excessive in terms of bank reserves even though bank lending remains modest, at best.

The short-run conflict that is going on right now is between the efforts of the Federal Reserve to stimulate bank lending and the financial system, and the efforts of families, businesses, and governments to reduce their debt loads. At the present time, the latter interests seem to be winning.

The longer run question relates to whether or not the government stops focusing just on short-run solutions to the problems of the economy and begins to focus on the longer-term structural problems that exist. The difficulty here is that it took a long time to get where we are now and it can be expected that it will take us a long time to get things back in order.

The real dilemma is that we don’t create more problems for the future by implementing short-run solutions to our problems that will just exacerbate our longer-run problems. In the long run we may all be dead, but we now seem to be dealing with the long-run problems left to us by earlier generations of policy makers that just focused on short-run solutions without any regard for the long run!

Leave a Reply