In an earlier part of my career, I spent a fair amount of time thinking about fiscal policy issues. The evolution of my responsibilities eventually moved my attentions in a somewhat different direction, but you never really forget your first research love. With questions of debt, government spending, and taxes at the top of the news, it isn’t hard for my old fondness for the topic to reemerge.

So, in that context, I had a somewhat nostalgic response to an item at Angry Bear, written by contributor Dan Crawford. In essence, the Crawford post formally (through statistical analysis) asks the question “How is GDP growth related to marginal tax rates (that is, the tax rate applied to your last dollar of income)?” More specifically, Crawford analyzes how gross domestic product (GDP) growth next year is related to the marginal tax rate faced by the average individual and the marginal tax rate faced by the highest-income taxpayers.

I don’t intend to quibble with the specifics of that experiment per se but rather highlight an aspect of taxation and tax reform that I think should not be forgotten. That is, the short run is no place for a decent discussion of tax policy to be hanging out. To say that more formally, the largest effects of tax policy accrue over time, and it is probably not a good idea to be too focused on the immediate—say, next year’s—effects of any given policy or change in policy.

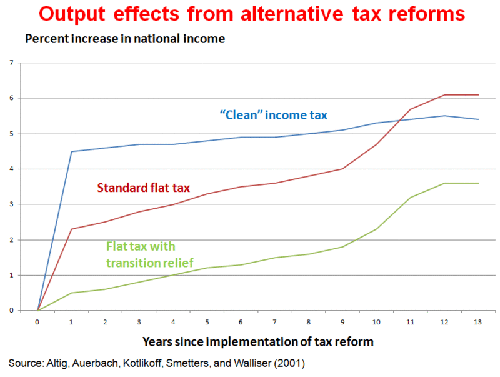

The following chart is based on tax reform experiments in a paper I co-authored over a decade ago with Alan Auerbach, Larry Kotlikoff, Kent Smetters, and Jan Walliser. (Note that the chart does not appear in the paper, but I created it using data from the paper—a publicly available version of the paper can be found here.) The chart depicts the cumulative percentage increases in national income that would be realized (in our model) in the years following three different tax reforms.

The three experiments depicted in this chart were as follows:

“[The clean income tax] replaces the progressive taxation of wage income with a single rate that is also applied to capital income. In addition, the clean income tax eliminates the major federal tax-base reductions including the standard deduction, personal and dependent exemptions, itemized deductions, the deductibility of state income taxes at the federal level, and preferential tax treatment of fringe benefits…

“Our flat tax experiment modifies the clean consumption tax by including a standard deduction of $9500. In addition, housing wealth, which equals about half of the capital stock, is entirely exempt from taxation.”

Parenthetically, the “clean consumption tax”

“…differs from the clean income tax by including full expensing of investment expenditures. This produces a consumption-tax structure. Formally, we specify the system as a combination of a labor-income tax and a business cash-flow tax.”

Finally,

“Our [flat tax with transition relief] experiment adds transition relief to the flat tax by extending pre-reform depreciation rules for capital in place at the time of the tax reform.”

Here’s what I want to emphasize in all of this. If the change in policy you might be considering involves a reduction in effective marginal tax rates (implemented via a combination of changes in statutory rates and adjustments in deductions and exemptions), the approach taken by Crawford in his Angry Bear piece is probably acceptable. The clean income tax reform is in the spirit of Crawford’s calculations, and in our results the long-run impact on output is realized almost immediately. If, however, the tax reform involves changing the tax base in a fundamental way (in both versions of our flat tax experiments the base shifts from income to consumption), then the ultimate effects are felt only gradually. In our flat tax experiments, the longer-run effects on income are in the neighborhood of three times as large as the near-term effects.

All of the experiments described were done under the assumption of revenue neutrality, so questions of the right policy for budget balancing exercises weren’t explicitly addressed. (Nor is it the nature of the experiment contemplated in the Angry Bear post.) Nonetheless, they do suggest that deficit reduction exercises that involve changes in tax rates and the tax base will have differential effects over time, and realizing the full benefits of tax reform may require a modicum of patience.

Note: A user-friendly description of the paper that the chart above is based on appeared in an Economic Commentary article published by the Cleveland Fed.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply