One of my long-time New York friends said: “If you have three people working in a McDonald’s there will be politics and grandstanding. Wall Street isn’t much different.” There’s more fame, and the fortune is much greater, but he’s on to something.

One of the reasons Warren Buffett has cultivated an image of trustworthiness is because his public persona seemed to be above it. Some contrast from my personal experiences may illustrate the point.

A Question of Character

A top hedge fund manager’s emails were made public as the result of discovery in a lawsuit. He derided the CEO of an insurance company using profane imagery and referred to the Canadian CEO, who was born in India, as a “schwarze,” a pejorative term for people of African heritage. In a Reuters article, I was quoted as saying the language speaks to character. The hedge fund manager emailed me to insult mine for speaking up (not to express regret for his choice of words revealed by Reuters). Perhaps he feels the best defense is a lame offense.

When performing due diligence, investors consider capacity, capital, and character. The hedge fund manager may underestimate how offensive his language appears to many people, including me. He may also disregard the multi-national and multi-racial make-up of the families of investors and colleagues.

People are sometimes unfairly judged by their age, race, birthplace, gender, height, deformities, or handicaps. Those are factors that are completely beyond their control.

Yet, I got the impression the hedge fund manager felt it was unfair for anyone to judge him for words that were completely within his control.

“What Motivates You?”

Late last year, another “top” hedge fund manager (with a mixed track record), I’ll call him the Yeti, said he’d like to talk to me about an idea he had that I should start a fund of funds. I found this a bit odd. I’d explained to him that I’ve publicly stated for years that I believe fund of funds managers add zero or negative value. Those that invested clients’ funds with Madoff are a recent example. If I were going that route, I’d start a fund. Nonetheless, he thought it worth discussing, so I met with him in his New York offices.

I was feeling particularly good that morning, and it showed. My mood seemed to annoy him. He asked a smarmy and chilling question: “What motivates you, Janet, is it sex?” I should add that he’s married and cultivates a press image as a family man. He’s also more than ten years my junior. He explained that I could hire only female employees, and then he’d introduce me to some people; I’d make a large fortune. He continued with his supposed motivation: “money makes sex a lot easier to get.”

“It’s dangerous to use one to try to get the other,” I responded. (Depending on the circumstances, it can also be illegal.)

What was the purpose of that meeting? Apparently, the Yeti was hoping to be educated as to why money cannot buy a better personality.

Not long after that, I publicly and separately disagreed with the Yeti on a business issue. He complained via email that our relationship was over. But there was no “relationship,” and nothing wholesome would develop from his “ideas.” Meanwhile the financial press profiles the Yeti as a role model, which is an abominable snow-job.

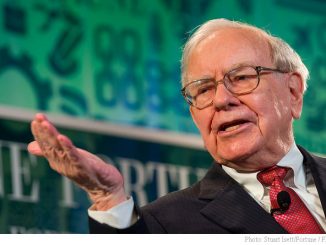

Buffett’s Gentle Treatment by the Financial Press

It’s easy to like Warren Buffett; he’s a relief in comparison. No financier has as long a track record or has garnered so much good press for so long as Warren Buffett, the CEO and largest shareholder of Berkshire Hathaway. His language and business demeanor has been exemplary, and his public statements against malfeasance and hubris have been a welcome oasis in a business riddled with multi-decade frauds and scandals. He’s been the rock star of the financial world.

It’s as if there was a pact among the financial press to overlook foibles as long as no scandal could be directly tied to Warren Buffett’s actions. Suddenly that’s changed.

Bloomberg’s Jonathan Weil reminded the financial community that the press has given Warren Buffett very gentle treatment in past scandals. Buffett stayed mum during the financial crisis as Moody’s (Berkshire owned around 19% of the stock at the end of 2007) handed out “AAA” ratings on junk bonds. He headed Coca-Cola’s audit committee, and the SEC issued a cease and desist order against the company for misleading earnings statements in the 1990’s. Warren Buffett knew about contracts between Berkshire’s GenRe unit and American International Group Inc. for which GenRe paid a $92 million fine and four executives were sentenced to prison. The SEC claimed Berkshire and its audit firm, Deloitte, violated the SEC’s auditor independence rules when one of Deloitte’s advising partners traded in and out of Berkshire’s stock; Berkshire concluded Deloitte was independent anyway, and the SEC didn’t object.

It’s noteworthy that none of the financial journalists with the most access to Buffett raised the issue that Buffett himself appears to have violated Berkshire’s disclosure policies as stated in a recent Berkshire Hathaway audit report on David Sokol’s violation of Berkshire’s insider trading policies. The “duty of candor” the non-independent audit committee applied to Sokol, a former executive, should also apply to Warren Buffett.

If It Isn’t “Unlawful,” Why Did Buffett Give the SEC “Very Damning Evidence?”

In a March 30 press release, Buffett announced David Sokol’s resignation and praised his track record. At Berkshire Hathaway’s April 29 Annual Meeting, he told of how Sokol turned down $12.5 million in incentive pay several years ago. Buffett didn’t mention that Sokol was Chairman of MidAmerican when plaintiffs in a lawsuit questioned Sokol’s calculations. A judge ruled there was a “breach of obligation” and awarded $32 million plus stock in a project company in damages.

In his March 30 release, Buffett wrote that Sokol’s purchases of shares of Lubrizol, a company targeted as a Berkshire Hathaway acquisition candidate, were not a factor in his decision to resign. Jonathan Weil retorted that the line “wasn’t remotely credible.” Buffett himself admitted at his Annual Meeting the trades were a firing offense.

Buffett tried to dodge the key issues at the Annual Meeting by saying that people were bothered by his March 30 release because they missed “some big sense of outrage.” Actually, the public has had enough phony outrage. Missing were candor and material facts.

The most important fact was that while Buffett wrote on March 30 that neither he nor Sokol felt the trades were “in any way unlawful,” after a month of press uproar, Buffett admitted at his Annual Meeting that on the day he wrote his release he turned over evidence to the SEC’s enforcement division that was “some very damning evidence, in my view.”

Now the rating agencies are reviewing weak corporate governance at Berkshire Hathaway and may downgrade the company’s credit rating. That would lead to relatively higher funding costs which would create a drag on returns.

Buffett didn’t think this incident wouldn’t damage his reputation, but perhaps as Jonathan Weil points out, the press has gone easy on him in the past. Buffett isn’t being judged on appearances. He’s being judged by words and actions completely under his control.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply