Economists have expressed fears over the macroeconomic consequences of falling home prices dragging down consumption in the US and other nations. This column says that housing values and consumption are indeed correlated, but once one takes into account the fact that housing price changes may be acting as a proxy for future expected income, the measured housing wealth effect, if it exists at all, is much smaller than popularly believed. That finding suggests that changes in housing wealth have little effect on consumption.

Much commentary in the financial press over the last several months has been concerned with the impact of falling house prices on consumer spending. While some see evidence of “green shoots” and hope for economic growth over the horizon, many still fear that lower home values will depress consumer spending. This “wealth effect” – a drop in home values that causes consumers to cut back on purchases – is thought to dampen economic growth and hamper any recovery.

At first glance, it seems reasonable to expect such a wealth effect. If consumers are less wealthy because of declines in the value of the assets they own – whether they be stocks or their homes – it seems logical that they would cut back on their spending. Indeed, many prominent economists have conducted research purporting to find large housing wealth effects, and they often argue that the wealth effect from homes exceeds that from equities. Moreover, the Federal Reserve employs a model, which presumably guides its policies, that assumes the housing wealth effect is large.

A more careful look at the data, guided by economic theory, however, suggests that much of this evidence has been misinterpreted and that the reaction of consumption to housing wealth changes is probably very small. First, several recent studies have shown that the logic of the housing wealth effect is faulty. Houses, unlike stocks, are not just assets but are also consumption goods themselves.

Theoretical papers by Todd Sinai and Nicholas Souleles (2005) and Willem Buiter (2008) cast doubt on the notion of a large spending effect from housing. Putting aside for the moment the question of how housing wealth may affect spending indirectly (via its effect on consumers’ access to credit), when considering the direct effect of housing wealth on consumption, it is clear that any decrease in house prices hurts only those who are net “long” in housing – that is, those who own more housing than they plan to consume. This might include, for instance, “empty-nesters” who are planning on selling their current houses and downsizing. On the other hand, the decline in home values helps those who are not yet homeowners but plan to buy.

Most homeowners, however, are neither net long nor net short to any significant degree; they own roughly what they intend to consume in housing services. For these households, there should be no net wealth effect from house price change. And when one thinks about the economy as a whole (which is a combination of all three types of households) the aggregate change in net housing wealth in response to house price change should be nearly zero; changes in house prices should affect the distribution of net housing wealth, but have little effect on aggregate net housing wealth. Thus any effect from net housing wealth change on aggregate consumption spending should be similarly small.

Put differently, increases in house prices raise the value of the typical homeowner’s asset, but such price increases are also an equivalent increase in the cost of providing oneself housing consumption. In the aggregate, changes in house prices will have offsetting effects on value gain and costs of housing services and leave nothing left over to spend on non-housing consumption.

Up to this point, we have neglected the question of whether housing wealth change affects consumption through another, indirect channel – a financing channel – by affecting consumers’ access to credit. For example, if houses serve as better collateral than other assets, then it is possible that “constrained consumers” (those who wish to borrow today and repay loans from anticipated increases in income in the future) may face better lending terms as the result of an increase in the value of their homes, which in turn may increase their non-housing consumption. Some observers point to the latest housing boom and the increased use of home equity lines of credit and other mortgages during the boom as evidence that housing prices spurred consumption through this financing channel. While this indirect financing channel is a theoretical possibility, it is an empirical question whether it is significant in its effect, and even if the indirect financial effect is present it should not produce a “first-order” effect of housing wealth on consumption – housing wealth should still matter much less for consumption than other forms of wealth.

It works in theory, why not in the data?

If theory suggests that housing wealth effects should be so small, then why have previous empirical studies found them to be so large? The most widely known empirical paper on the housing wealth effect is likely by Karl Case, John Quigley and Robert Shiller, published in 2005. The authors constructed a data set for housing wealth based on price indices and the number of housing units for all of the fifty US states over 1982-1999. The construction of this dataset was a major contribution, as other studies had relied on less precise and more aggregated time series measures of housing wealth. Case, Quigley and Shiller found a large consumption effect from changes in housing wealth and furthermore found that this housing wealth effect was larger than the effect on consumption from changes in equity wealth. (The authors also reported a puzzling finding that this housing wealth effect was asymmetric – an increase in housing prices raised consumption, but a decrease in home values did not lower consumer spending.)

But the estimation method used by Case, Quigley and Shiller was problematic. They failed to take account of a simultaneity problem – the possibility that both consumption and housing prices were driven by changes in expected future income. In our study (Calomiris, Longhofer, and Miles 2009), we investigate whether changes in economic optimism or pessimism about the future (a change in expected permanent income) might be driving the correlation between house prices and consumer spending.

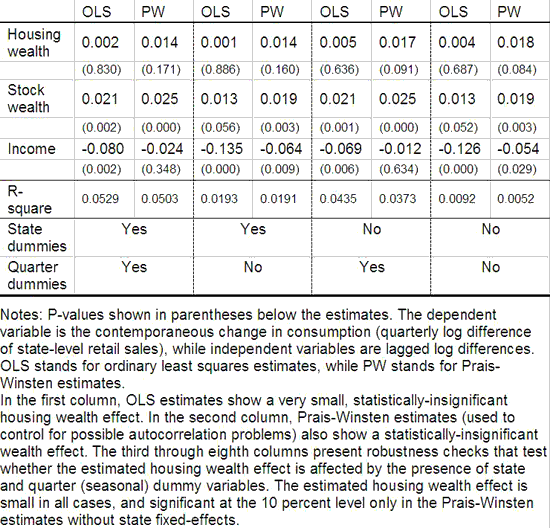

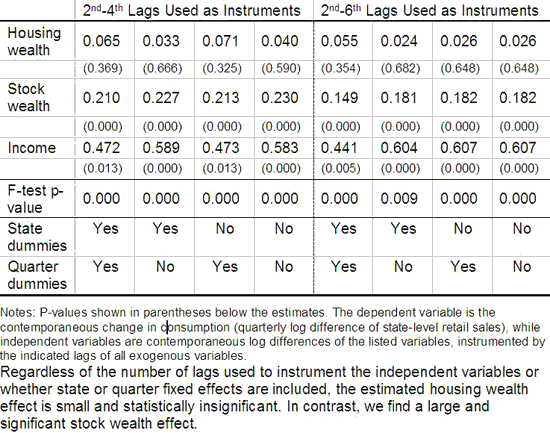

New estimates that control for long-run income effects

We apply instrumental variable estimation and two-stage least squares to the data to correct for this simultaneity problem. As noted in the tables at the end of this column, when we do so, the specifications closest to those of Case, Quigley and Shiller indicate no housing wealth effect. We put the data through numerous robustness checks and found in most model specifications that housing wealth had zero effect on consumption (see our working paper). In those few cases where housing wealth did have an impact on consumer spending, the impact was always smaller in magnitude than that from stock wealth, contrary to Case, Quigley and Shiller’s findings. We conclude that the impact of housing wealth on consumption, if it exists at all, is much smaller than popularly feared. (See the end tables for details.)

Other researchers have analysed data from Great Britain and have similarly found that, once one takes simultaneity problems into account, there is also little, if any, housing wealth effect in that country. Orazio Attanasio, Laura Blow, Robert Hamilton, and Robert Leicester (2009) express scepticism that a large housing wealth effect exists, and find, for instance, that (without correcting for simultaneity bias) the “wealth effect” appears to be the same for renters and homeowners. This would make no sense if household spending were really driven by housing wealth, because renters are actually hurt by rising home prices. They conclude, as we do, that housing wealth is acting mainly as an indicator of changes in perceived economic prospects, which apply to homeowners and non-homeowners alike.

What it means for policy

These results have important implications for public policy. In particular, they suggest little gains in macroeconomic growth from policies targeted specifically at boosting housing prices in order to spur consumption. Of course, the absence of a housing wealth effect should not be interpreted as suggesting that housing is unimportant for the US business cycle. To the contrary, recent research by Edward Leamer (2007) of UCLA, published under the self-explanatory title “Housing IS the Business Cycle,” provides very strong evidence that housing has a larger impact on output than any other sector, and that housing is by far the best leading indicator of economic activity. And there are a number of channels through which housing can cause cyclical fluctuations other than the wealth effect. Indeed, Professor Leamer himself is sceptical that the housing wealth effect is an important channel through which housing affects the business cycle.

The current downturn in the housing market, with its attendant impact on our recession, has been accompanied by many policy proposals. To craft truly constructive policy, it is vital that the channels through which housing affects our economy be properly understood. While consumer spending may be sluggish in the near future for other reasons, it is doubtful that recent declines in home values will be a major contributor to this problem.

References

•Attanasio, O., L. Blow, R. Hamilton and A. Leicester (2009) “Booms and Busts: Consumption, House Prices and Expectations,” Economica, 76, 20-50.

•Buiter, W. (2008) “Housing Wealth isn’t Wealth,” NBER Working Paper 14204.

•Calomiris, C.W., S.D. Longhofer and W. Miles (2009) “The (Mythical?) Housing Wealth Effect,” NBER Working Paper 15075.

•Case, K., J. Quigley and R. Shiller (2005) “Comparing Wealth Effects: The Stock Market versus the Housing Market,” Advances in Macroeconomics, 5, pp. 1-34.

•Leamer, E. (2007) “Housing IS the Business Cycle,” NBER Working Paper 13438.

•Sinai, T. and N. Souleles (2005) “Owner-Occupied Housing as a Hedge Against Risk,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120, 763-789.

End Tables

Table A1. Panel data wealth effect estimates

Table A2. Panel data 2SLS wealth effect estimates

![]()

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply