China’s GDP growth continued at a blistering pace during the first quarter of 2011, rising 9.7 percent from the previous year, according to economic data released today from the People’s Bank of China. Once again this outpaced many forecasts—even that of the Chinese government—and reignited the discussion of China’s overheating economy. While its robust growth may raise a few eyebrows, the economy isn’t in danger of “red-lining.”

Andy Rothman, from Credit Lyonnais Securities Asia (CLSA) points out that the first quarter growth figures “[aren’t] dangerously high given the GDP growth rate and strong income growth” in the country. After rising nearly 8 percent during 2010, inflation-adjusted urban incomes rose 7.1 percent during the first quarter, according to CLSA. Rural incomes grew at 14.3 percent, up from just under 11 percent in 2010.

Fixed asset investment (FAI) also remains strong. China’s FAI grew 25 percent during the first quarter, a reversion to the long-term pace of FAI growth China saw for six-straight years prior to the government’s stimulus plan in 2009.

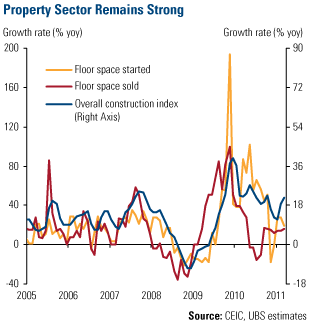

This pace is supported by a property sector that refuses to slow despite Beijing’s multiple efforts to tap the brakes. Property sales grew 15.8 percent on a year-over-year basis and commodity housing starts grew 19.5 percent in March. You can see from this chart that this is a much more manageable pace than the stimulus-induced spike we saw in March 2010. Current levels are much more on par with long-term trends.

This pace is supported by a property sector that refuses to slow despite Beijing’s multiple efforts to tap the brakes. Property sales grew 15.8 percent on a year-over-year basis and commodity housing starts grew 19.5 percent in March. You can see from this chart that this is a much more manageable pace than the stimulus-induced spike we saw in March 2010. Current levels are much more on par with long-term trends.

Much has been said about empty housing prices in cities such as Shanghai and Beijing but UBS says that the sharp drop of sales in tier-1 cities have been more than offset by strong sales in most tier-2 and tier-3 cities. These are cities, such as Taiyuan and Xi’an in northwest China, which generally have urban populations of about 4-to-6 million people and are located away from China’s densely populated coastal areas.

Development in the interior has been a substantial driver in continuing China’s rapid growth. Insatiable construction demand from these inland regions helped push sales of wheel loaders—up 45 percent—and excavators—up 58 percent—during the first quarter. In addition, planned investment of FAI under construction rose 19.1 percent, according to CLSA. In addition, the government’s plans for extensive investment in social housing development—10 million units this year, in addition to carry-forward projects from last year—should provide an extra boost.

Chinese trade data released last week showed a 32.6 percent rise in imports during the first quarter. This figure includes a 12 percent rise in crude oil, 38 percent rise in metal-cutting machinery and a 32 percent rise in auto/auto-chassis from a year ago.

All of these factors are very supportive of demand for commodities such as cement, iron ore and copper.

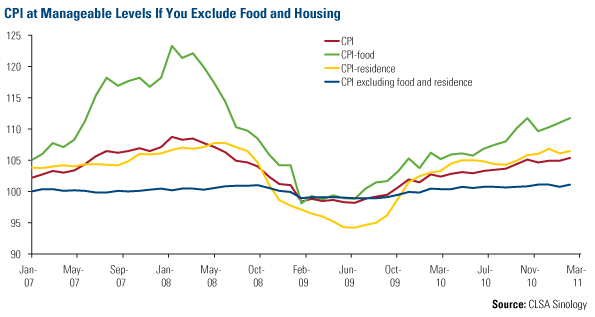

China’s biggest threat continues to be inflation. The country’s Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose 5.4 percent in March, the largest rise in nearly three years. This is certainly something to keep an eye on but not yet at the levels needed to hinder growth or, more importantly, cause social unrest. Chinese government has been pulling all stops to curtail inflation. Recently, 24 commerce associations across the country have made a joint statement to support the government’s effort to defeat inflation. China Premier Wen Jiabao called on local government officials last week to help stabilize consumer product and housing prices.

Food prices rose about 11 percent in March, contributing about two-thirds of the increase in CPI. You can see from this chart that if you exclude food and residential inflation—which was up 23 percent—the inflation levels appear quite manageable.

The rise in food prices is a result of external factors and not symptomatic of an overheating economy. However, the rise in incomes we referenced previously negates a portion of this. In addition, CLSA’s Rothman thinks we are either at or close to the peak in food price inflation.

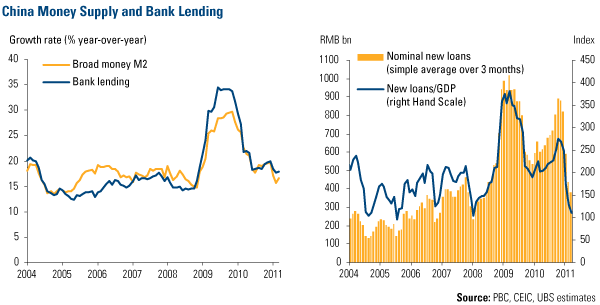

China’s March money supply (M2) growth rate was 16.6 percent. This was higher than February but 3.1 percent lower than the same period last year. This may be close to the government’s target money growth rate since it is in line with those prior to financial crisis. We think there is still room for money supply to further contract without damaging the government’s target GDP growth rate.

To control money supply, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) has raised its reserve requirement ratio (RRR) for the sixth time since October 2010, bringing the ratio to a record high of 20 percent. The chart on the left shows how this has effectively slowed bank lending, and thus, money supply. Given that China’s inflation battle is not over yet, we believe the PBOC will continue to raise RRR to further slow money supply.

The chart on the right shows that bank lending is declining in China. After adding Rmb 679 billion new bank loans in March, China’s total bank lending this year is Rmb 2.24 trillion. Without an official loan target for this year, the market’s opinion is that the unofficial PBOC target is around Rmb 7.5 trillion—roughly the same as in 2010.

However, the current new loan speed is certainly more than the PBOC can allow. We expect the PBOC may allow a little more lending earlier in the year, before tightening more toward the end of the year, after a clearer picture forms of where the economy is headed.

Other tightening policies are likely to be completed by the first half of the year and with inflation apparently under control, money supply back to historical levels and food prices peaking, it appears that the government will be successful in engineering a soft-landing.

China analysts Xian Liang and Michael Ding contributed to this commentary.

Percentages refer to year-over-year (yoy) change unless otherwise specified.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply