Income inequality in America has soared over the past generation. But some see little cause for concern. One reason is that our inequality statistics — Gini coefficient, share of income going to the top 1%, and so on — are calculated based on households’ income in a single year. This misses the fact that people move up and down over time. Our incomes in any given year may be more dispersed now than several decades ago, but if many of us are switching places from year to year, why the fuss?

Two claims need to be distinguished here. One says there’s enough movement up and down in the income distribution over time (in technical lingo, relative intragenerational income mobility) that we needn’t worry about single-year inequality at all. It doesn’t matter whether inequality is high or low; it doesn’t matter whether it’s rising or falling. Single-year income inequality is simply irrelevant, on this view, because there is a lot of mobility. Since “a lot” and “enough” are in the eye of the beholder, evidence can’t confirm or refute this claim.

A second claim says that the rise in income inequality has been offset by a rise in mobility. Here we can look to the data for a verdict. Has income mobility increased?

For the bulk of the population — everyone but the richest — we have multiple sources of mobility data. One is the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID); another is earnings records from the Social Security Administration. Both indicate that there has been no increase in income mobility in recent decades (see also here).

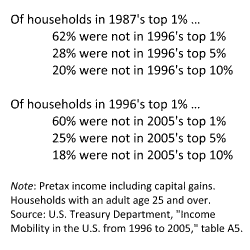

What about at the top? A good bit of the past generation’s rise in inequality consists of growing separation between the rich, especially the top 1%, and the rest of America. But has this been accompanied by increased churn among those at the top? In 2007 the Treasury Department released a study based on analysis of tax records. It included data on movement out of the top 1% over two nine-year periods: 1987-1996 and 1996-2005.

Single-year income inequality rose sharply during these two periods. The share of income going to the top 1% of households jumped from 11% in 1987 to 14% in 1996 to 18% in 2005. The Treasury study found that mobility, by contrast, was essentially unchanged.

The large increase in income inequality has not been offset by a rise in mobility at the top.

Leave a Reply