Incoming data continues to confirm an emerging period of relative economic tranquility following the financial storm of 2008. Importantly, the bleeding in consumer spending has been staunched, despite ongoing job losses that look likely to remain a feature of the American economic landscape for months to come. But incoming data also point to America’s sustained and perplexing dependence on foreign capital inflows – a dependence that suggests an underlying economic vulnerability that has yet to be addressed. Whether it needs to be addressed next month, next year, or next decade is still a question that continues to haunt the followers of global macro trends.

The most recent Personal Income and Outlays report, for May 2009, highlights many of the trends currently impacting the evolution of economic activity. The headline jump in incomes, like that of the pervious month, was driven by federal stimulus. Declining private wage and salary disbursements are a more telling indicator of the health of household finances, and are consistent with ongoing labor market weakness. The best bet is the that private wage gains remain subdued, even as conditions stabilize. Although the apparent peak of initial claims is in the rearview mirror, persistent high levels of claims points to a jobless recovery.

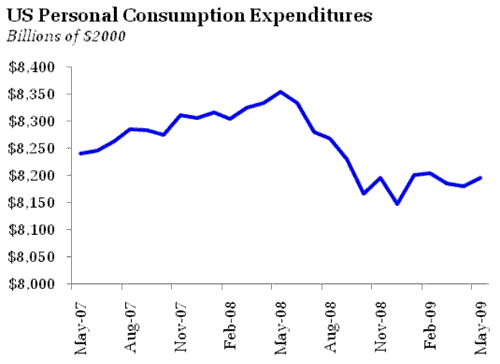

Of course, in the absence of federal stimulus, the underlying weak income growth indicates sustained pressures on consumer spending power. Indeed, the numbers tell a clear story of stabilization, but little to suggest that a V shaped recovery for consumer spending is at hand:

In addition, the report adds further credence to the claims that American’s long affair with spending has ended in a bitter divorce, with the saving rate climbing to its highest level in 15 years. To be sure, some of the increase is likely not sustainable in the short run, as it partly reflects a time lag between federal stimulus and the spending it was meant to encourage. That said, the underlying saving increase is tempering the impact of stimulus spending, as households sock some of it away for the next rainy day and/or pay down crippling debt loads, effectively turning private debt into public debt. And note that large shifts in consumer behavior are not required to have significant macroeconomic implications. Small changes across households – a little less, percentage wise, spending here and there adds up. From Bloomberg:

Saks Fifth Avenue is cutting orders 20 percent after posting losses in the last four quarters. Kia Harris says some customers at the Washington shoe store where she works are buying one pair rather than three.

In the recession following a borrowing binge that sent consumer debt to the highest level ever, Americans are shutting their wallets and building their nest eggs at the fastest pace in 15 years.

While the trend will put the country’s finances in better balance and reduce its dependence on Chinese investment, it may also restrain economic growth in 2010 and beyond, said Lyle Gramley, a senior economic adviser with New York-based Soleil Securities Corp. and a former Federal Reserve governor.

The interesting line here is the implication that increased savings will jointly improve national finances and lessen dependence on foreign capital inflows. To be sure, the increase in household saving or, equivalently, the decrease in household borrowing serves as the offset for increase federal borrowing. Indeed, the data is supportive of those who argue the importance and necessity of deficit spending to support economic activity. Given that low interest rates are insufficient to spur spending and, instead, households rapidly increase the pool of available saving, the federal government is best positioned to step up as the economic engine, and can do so without significantly impacting interest rates and crowding out private investment. Case closed.

Or is it? In closed economy, this story works. In an open economy, the tangled webs of international finance are spun into a more complex tale. Why, if rising households saving justifies deficit spending, are foreign central banks increasingly important again in financing a US capital shortfall? From Brad Setser:

Over the last 13 weeks of data, central banks added $160 billion to their custodial accounts, with Treasuries accounting for all the increase.

$160 billion a quarter is $640 billion annualized — a pace that if sustained would be a record. Of course, $640 billion in central bank purchases of Treasuries would still fall well short of meeting the US Treasuries financing need. The math only works if Americans also buy a lot of Treasuries. That is a change.

The annualized inflow of $640 billion is nothing to sneeze at; at that rate, foreign central banks are supporting US spending to the tune of 4.5% of GDP. Without those inflows, I find it difficult to think that US interest rate would have anywhere to go but up – an increase that would be necessary to resolve what remains a persistent element of the American economic landscape – a smaller but still significant current account deficit. A deficit that could perhaps be dismissed if it was being financed by individual investors in Shanghai looking to be shares in Apple to capture the profit potential of the US economic engine. A deficit that is difficult to dismiss if it requires foreign central banks to continually compensate for the absence of interest from private investors.

The ongoing US dependence on foreign central banks, long chronicled by Brad Setser, has another implication. If foreign CBs only provided temporary financing, we could rightly view their actions as addressing a temporary liquidity crisis in the US. No harm done, good stabilization policy. The persistence of those flows, however, suggests something much darker…the US does not face a liquidity challenge. It faces a solvency challenge. From the Washington Post:

The nation’s long-term budget outlook has darkened considerably over the past six months, and President Obama’s plan to extend an array of tax cuts and other policies adopted during the Bush administration has the potential to “create an explosive fiscal situation,” congressional budget analysts reported yesterday.

In a new report, the Congressional Budget Office found that extending the Bush administration tax cuts, reining in the alternative minimum tax and canceling a scheduled reduction in payments to Medicare doctors would dramatically slash tax collections at a time when federal spending would be “sharply rising.” The resulting budget gap would drive the nation’s debt over 100 percent of gross domestic product by 2023, the report says, and past 200 percent of GDP by the late 2030s.

Quite honestly, I find the implementation of temporary fiscal spending to fill an economic hole something of a no brainer at the current time; the likely persistence of deficit spending long into the future is cause for concern. It is cause for concern because it is a problem that likely just builds so long as there is no market mechanism to signal a need for meaningful change. The obvious signal would be rising interest rates. But so long as foreign central banks are willing to be the buyers of last resort for US Treasuries, interest rates will remain in check; external policymakers will ensure that the US continues to receive the financial support to keep the dynamic in play.

When will this dynamic be brought to an end? Still the multi-billion dollar question. Chinese policymakers see the writing on the wall, as they played no small part in sustaining US spending prolificacy:

The dollar declined the most against the euro in a month and dropped versus the yen after China repeated its call for a new global currency.

The Swiss franc declined against the euro and dollar this week as foreign-exchange analysts said the central bank sold its currency three times to support the economy. The greenback fell against most of its major counterparts after the People’s Bank of China said yesterday the International Monetary Fund should manage more of members’ foreign-exchange reserves.

“The dollar’s status as a reserve currency is being questioned,” said Benedikt Germanier, a foreign-exchange strategist in Stamford, Connecticut at UBS AG, the second- largest currency trader. “There are reasons to sell the dollar.”

This, however, does not appear to be a realistic stab at the bringing about greater balance to the global economy. China wants to sustain large current account surpluses while avoiding any portfolio risk on the offsetting rise in official reserves. Ironically, the US wants the opposite – steady inflow of cheap goods without the risks associated with a large build up of external assets. All players want upside without risk. We are all well versed at this point with the wisdom of pretending that everyone can shed risk. It doesn’t disappear in those situations; it becomes concentrated. Think AIG.

In any event, for now Chinese angst appears to be meaningful saber-rattling, as each threat to change behavior is quickly retreated from. Bloomberg this morning:

People’s Bank of China Governor Zhou Xiaochuan said the nation won’t change its currency reserve policy suddenly, helping the dollar to snap a two-day decline.

“Our foreign-exchange reserve policy is always quite stable,” Zhou told reporters at a central bankers’ meeting yesterday in Basel, Switzerland. “There are not any sudden changes.”

Sudden changes in the Dollar’s status as a reserve currency serve no purpose. Best instead to use a pattern of outright threats and changes in patterns in bond purchases to keep American policymakers aware of the ultimate cost of Dollar hegemony. Given that as of yet, there is no realistic alternative to holding Dollars, policymakers globally slavishly heed to past behaviors that have entrenched global imbalanced, hoping the problem spontaneously disappears. But instead, it only grows, looming like a dark shadow over the global macroeconomy.

What are the policy options? Short of imposing capital controls, open capital markets implies we can’t stop foreign central banks from accumulating US assets. Long needed has been an international agreement that brings sanity to the seemingly insane equilibrium in which poor nations finance the spending of rich nations. Such a voluntary, multilateral withdrawal from the current regime, however, remains little more than a bedtime story.

Domestically, the optimal path is to meaningfully address the long term budget challenge. Does this mean cutting programs and boosting taxes now? No, quite frankly, at this juncture that would be an almost insane policy response, one that would not be appropriate for either the US or our trading partners. In the short run, such as policy response would be needlessly disruptive (indeed, that potential disruption is what keeps foreign central banks in the game of buying US Treasuries). Instead, you need to examine the policy space to find an obvious candidate for controlling the growth of aggregate spending in the US. And that exercise always leads you back to health care, and the realization that we spend an extra $1 trillion more than other industrialized nations, and we don’t get much if anything for it. A trillion dollars is a lot of money; more in fact, than the recent pace of foreign central bank Treasury purchases. If you can meaningfully “bend the curve” on health care spending, you can see a light at the end of the tunnel. If you can’t or are not willing to bend the curve, I fear waning global patience in sustaining US spending will result in a rude awakening that the tunnel of US fiscal policy ends at a hard wall.

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply