The fundamental nature of the recession continues to be debated – a debate with important policy consequences. Is the recession the consequence of a general aggregate demand deficiency, or is it a structural consequence of the housing bubble? If the former, the policy approach should be to support aggregate demand via a combination of fiscal and monetary policy. If the latter, only time will resolve the challenge, and aggressive policy will only lead to inflation.

David Beckworth and Ryan Avent provide nice summaries of the nature of the debate. Paul Krugman argues that the answer is obviously a demand shortfall, and bemoans:

Now, however, we’re seeing a much more widespread attack on demand-side economics. More than that, it’s becoming clear that many people don’t so much disagree with the idea that demand matters as find it abhorrent, incomprehensible, or both.

Nick Rowe offers an alternative explanation:

For decades my job has been to teach students that, despite the evidence of their senses, and contrary to their hearsay of the heretical teachings of the Keynesian Cross, aggregate output is basically supply-determined. Which it is. Basically. Though short-run fluctuations in demand can and will cause short run fluctuations in aggregate output around an average level that is determined by the supply-side.

And, for once, the memories of their parents are actually supporting me in my job. Look what happened in the 1970’s, when demand increased. Printing too much money and increasing demand really did cause inflation. It really didn’t make us all richer. It didn’t reduce unemployment.

Now, just for once, we have to switch gears. These times are not normal. Just for once, the demand side really is the problem. Just for once, the overly obvious truth your senses are telling you really is the truth. Just for once, your parents’ experience of the 1970’s doesn’t apply. Just for once, it really is OK to have a drink, even though you are a recovering alcoholic.

In some sense, economists diluted the reasoning of demand side macroeconomics with a focus on supply side factors. The Great Moderation only served to entrench the supply side view – after all, by the late-90’s I recall articles suggesting that we had conquered the business cycle. Demand side fluctuations had become a thing of the past.

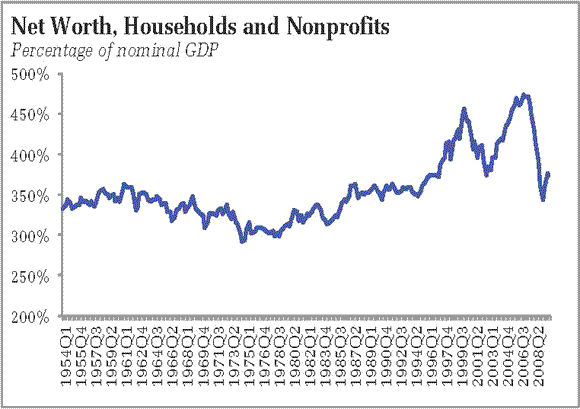

I would offer another observation. I agree that the issue is a shortfall in demand. And not just for this recession, but arguably the entire last decade. That said, I think it is easy to lose sight of this demand shortfall in light of another feature of the past two business cycles. Both appear to have been inexorably connected to asset price bubbles, first in information technology and then in housing:

Supporting sufficient aggregate demand to maintain full employment looks to have required supporting relative levels of net worth well above a decades-long baseline. And pushing net worth to those levels was a consequence of asset price bubbles. Hence, it appears that the demand generated by that wealth was “fake.” Moreover, that “fake” demand arguably induced a supply side effect by pushing capital first into information technology and then into housing. To be sure, ultimately the impacts of such capital misallocations will fade away. Information technology depreciated rapidly, and the excess housing stock will eventually be absorbed by a growing population. It is not quite obvious, however, why this adjustment needs to extend to such a large portion of the workforce. The answer, I think, is not the housing adjustment itself, but the loss of general demand precipitated by the housing decline and subsequent balance sheet malaise.

The wealth-supported demand surely was not “fake,” as real goods and services were indeed purchased. But it was ephemeral, evaporating with the popping of bubbles. So it should be of little surprise the Federal Reserve is viewed by some as doing nothing more than supporting another round of “fake” demand. Fed officials probably compound this problem by citing the stock market increase as evidence that QE2 is working. Via the Wall Street Journal:

In recent weeks, the Federal Reserve has been turning to an unusual metric to prove the potency of its bond-buying program: the stock market.

Comments from Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke and other officials, as well as research by the central bank, cite rising stock prices as a sign that the central bank’s $600 billion bond-buying program is working to bolster the economy.

Of course, it is perfectly reasonable for officials to note that high equity prices signal improving economic prospects, the latter a consequence of their policy stance. Some, however, may interpret this as further evidence that the Fed is simply trying to create another asset price bubble, which will, if history is any guide, will also prove to be fleeting. The resulting aggregate demand will then be viewed as “fake.” In this light, the Federal Reserve is not really fixing anything, just papering over the underlying problem.

In short, I appreciate hesitation to embrace “more money” as a solution when it appears that “more money” was part of the problem. Indeed, I used to be more sympathetic to that notion than I am now.

But what exactly is the underlying problem? Or is there an underlying problem? I don’t know that we have agreement on that. Why was the US economy dependent on asset bubbles to spur demand over the past decade, and will the same be true for the next decade? Is the Fed’s current policy stance destined to fuel another bubble? I don’t think that is a excuse to forego monetary and fiscal support – the alternative of ongoing high unemployment is not particularly enticing – but I think we would all feel a bit more comfortable if the next decade sees robust growth without an asset price bubble.

Leave a Reply