Total Industrial Production was unchanged in September, which was well below the expected 0.3% increase. In September, total production fell by 0.2%, reversing a 0.2% increase in August. Relative to a year ago, total Industrial Production is up 5.3%, down from a year-over-year increase of 5.4% in September.

On the surface, these numbers are disappointing, as September was the first decline in overall industrial production since June 2009 (the month the recession “officially” ended) and there was no rebound this month. However, if one digs just a little bit deeper, the report was not all that bad.

Total Industrial Production includes not only the output of the nation’s factories, but of its mines and utility power plants as well. The production and consumption of electricity generally has as much to do with the weather as it does with overall economic activity.

October was much milder than most Octobers, and thus had a lower-than-normal demand for electricity. Thus it is important to look at just how the manufacturing sector is doing alone. It rose 0.5%, and the September decrease was revised to down to 0.1% from 0.2%. Year-over-year factory output is up 6.1%, up from last month’s year over year increase of 5.4%.

Utility output fell by 3.4% in October following a 2.2% decline in September, and that came after a 1.0% fall in August. Year-over-year Utility output is down 2.6%.

The third sector tracked by the report is Mining (including oil and natural gas). The output of the nation’s mines fell by 0.1% after a 0.1% rise in September. Year-over-year mine output is up 7.5%.

Stages of Production

By stage of production, output of finished goods rose by 0.4% after falling 0.2% in September but that was after a 2.3% jump in August. Year over year, finished goods production is up 4.9%.

Finished goods are separated into consumer goods and business equipment, and there is a real dichotomy between the two. Consumers are trying hard to rebuild their balance sheets. That means spending less on current consumption while paying down debt and building up savings. That is a tough thing to do when you are unemployed, but the 90.4% of people who are working are doing their best to get their personal fiscal houses in order.

In addition, a large part of consumer finished goods are imports, not made here in the U.S. Output of finished consumer goods was unchanged in October after having fallen by 0.5% in each of the two preceding months. Year over year, output of consumer goods is up 2.6%.

Business equipment output, on the other hand, has been surging, rising 1.1% in October on top of increases of 0.3% in September and 0.2% in August, and up 10.4% year over year. Business investment in Equipment and Software has been one of the strongest parts of the economy, contributing 0.80 points of the 2.00% total growth in the economy in the third quarter, even though it makes up just 7.1% of GDP. It looks like it will be another strong contributor in the fourth quarter as well.

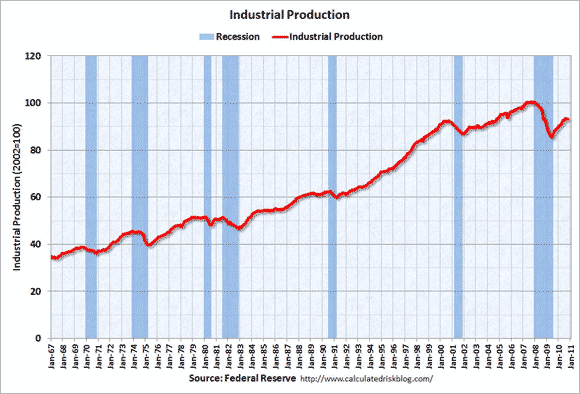

Output of materials fell 0.1% in October after increases of 0.2% and 0.7% in September and August, respectively. Materials output is up 6.7% year over year. The first graph (from http://www.calculatedriskblog.com) below shows the long-term path of total industrial production. While we are in much better shape than we were a year ago, total production is still well below pre-recession levels. That is not particularly unusual a year or so after the end of a recession; it usually takes at lest two years after production bottoms to reach a new high. And in the Great Recession, it fell much more than it had in any previous downturn.

Capacity Utilization

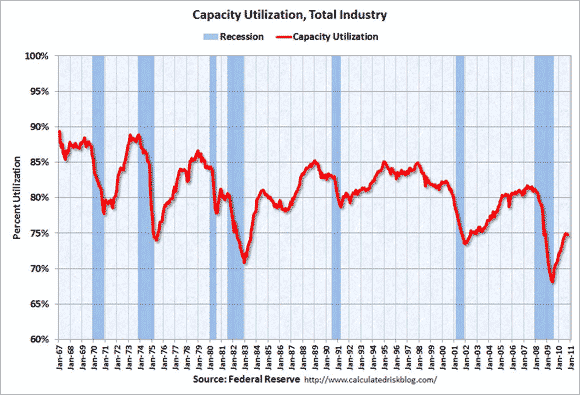

The other side of the report is Capacity Utilization. This is one of the most underappreciated economic indicators out there, and one that deserves a lot more attention and ink than it usually gets.

Total capacity utilization suffers from the same weather-related drawback as does Industrial Production. However, it was unchanged at 74.8%. although September was revised up from 74.7% and August was revised up from 74.8 to 74.9%.

The revival of capacity utilization has been going on for more than a year now. A year ago, just 70.7% of our overall capacity was being used, and that was up from a record low of 68.2% in June 2009.

The basic rule of thumb on total capacity utilization is that if it gets up above 85%, the economy is booming and in severe danger of overheating. This is effectively raises a red flag at the Fed and tells them that they need to raise short-term interest rates to cool the economy. It is also a signal to Congress that it is time to either cut spending or raise taxes, also to cool down the economy (Congress seldom listens to what capacity utilization is saying, but the Fed does).

Capacity utilization of around 80 signals a nice healthy economy, sort of the “Goldilocks” level, not too hot, not too cold. The long-term average level is 80.6%. A level of 75% is usually associated with a recession.

The Great Recession was the only one on record where it fell below 70%. Thus a 6.6% improvement in overall capacity utilization from the lows is highly significant and very good news. On the other hand, we still have a very long way to go for the economy to be considered healthy. The second graph (also from http://www.calculatedriskblog.com) shows the path of total capacity utilization since 1967.

Factories

Factory utilization rose to 72.7% from 72.3% in September (revised up from 72.2%) and 72.2% in August. That is up from 68.2% a year ago, and the cycle (and record) low of 65.4%. That is still well below the long-term average level of 79.2%, so as with total capacity, we still have a long way to go on the factory utilization level.

The increase in utilization over the last year, both total and factory, has been aided by a decline in capacity, with the total falling 0.4% and factory capacity dropping 0.3%. If some factories are closed and dismantled, it is easier to run the remaining ones closer to full time.

Mines

Mines were working at 87.9% of capacity in October, down from 88.0% in September and August. A year ago they were only operating at 81.8% and the cycle low was 79.6%. We are actually now above the long term average of 87.4% of capacity.

Since there is a lot of operating leverage in most mining companies, this probably means very good things for the profitability of mining firms with big U.S. operations like Freeport McMoRan (FCX) and Peabody Energy (BTU). Mine capacity was unchanged year over year.

Utilities

Utility utilization dropped to 76.6% from 79.4% in September and 81.3% in August. This is lower than it ever got during the official portion of the Great Recession, when the cycle low was 77.6%. We are far below the long-term average utilization of 86.7%.

The decline was probably more a function of the weather than a change in economic activity, while the year-over-year increase is probably more reflective of a better economy. Increasing utility utilization faces a headwind because, unlike factories, our power plant capacity has actually been increasing significantly, up 1.6% year over year.

The drop in utility utilization is a significant distorting factor in the overall figures for both utilization and production figures. In assessing the state of the overall economy, it is better to just look at the manufacturing numbers.

Stages of Processing

By stage of processing, utilization of facilities producing crude goods (including the output of mines) rose to 87.3% from 87.2% in September and 86.6% in August. A year ago, crude good facilities were operating at just 81.2% of capacity, and the cycle low was 78.3%. We are now above the long-term average of 86.5%. On the other hand, capacity has declined by 0.8% over the last year.

The same cannot be said for utilization for primary, or semi-finished, goods. It fell to 71.0% from 71.5% in September and from 72.1% in August. While that is much better than the 67.9% level of a year ago, and the cycle low of 65.7%, it is a very long way from the long-term average of 81.6%.

Utilization of facilities producing finished goods rose to 74.5% from 74.0% in September and 73.9% in August and is up from 70.7% a year ago, and a cycle low of 67.5%. It also remains below its long term average of 77.5%. Interestingly, our capacity to produce finished goods has actually increased by 0.7% over the last year.

Disappointing; Blame the Weather

Overall, this report was slightly disappointing, but most of the disappointment can be traced to more mild than normal seasonal weather. Once that is accounted for, it seems clear that we are headed in the right direction, but still have a long way to go.

The low levels of capacity utilization are one of the key reasons that inflation has remained low, and is not much of a threat in the intermediate future. This gives the Fed free reign to not only keep short-term interest rates at extraordinarily low levels for an extended period of time (probably until at least the end of 2011) but to take even more aggressive steps to ease monetary conditions, such as QE2. While under ordinary circumstances, doing so would raise a big threat of inflation accelerating; we do not live in ordinary times.

Right now the bigger threat is deflation, not runaway inflation. Or, at least it is in the absence of QE2. The bond market clearly seems to agree. Before QE2 was announced, the yieled on the 10-year note had fallen to under 2.4%. There is no other rational explanation for 10-year T-note yields to be that low unless people think that prices will actually be falling.

Since the announcement of QE2, T-note yields have actually risen sharply (but still at historically low levels), despite the large incremental buying pressure of the Fed. The bond market is seeing the threat of deflation recede.

Recovering – But a Long Way to Go

While the economy is recovering, it is still running at levels far below its potential. The capacity utilization numbers can be thought of as sort of like the employment rate from physical capital, much like the employment to population rate is the employment rate for human capital. Both are running well below where we want them to be.

While additional monetary stimulus would be useful at the margin, the cost of capital is not the major issue right now, it is lack of aggregate demand. As such, additional fiscal stimulus would be much more effective in getting the economy going again.

With long-term rates on T-bonds near historic lows, financing the higher deficits is not a problem. Getting the economy back into high gear would also start to raise tax revenues, and so the net cost of additional stimulus would be far less than the advertised amount. Of course, the two are not mutually exclusive and the economy would benefit from both being used.

Unfortunately, fiscal policy is likely to be headed in the wrong direction, towards austerity and the cutting of spending at the Federal level. We have been seeing anti-stimulus from the State and Local level throughout the Great Recession, and it is the total amount of fiscal stimulus that counts for the economy, not just what happens at the Federal level.

De-stimulus from the lower levels of government has offset about half of the Federal Stimulus we got from the ARRA. Those voices that are calling on the Fed to cease and desist from QE2 really seem interested in making sure that the economy does not get back on track. Monetary stimulus is not the best tool for getting the job done, but it is the only one left on the table in the current political climate.

Leave a Reply