Thanks to Scott Grannis for his excellent post today on China’s alleged “manipulation” of its currency, and claims that China’s currency policy harms the U.S. economy. Scott makes the following key points (and provides the charts above):

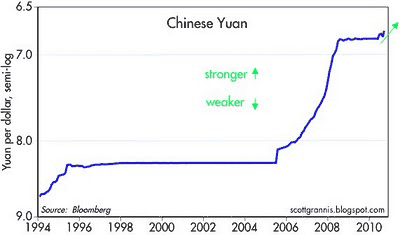

1. China’s current has in fact appreciated, by 23%, since it began pegging the yuan in 1994 (see top chart above).

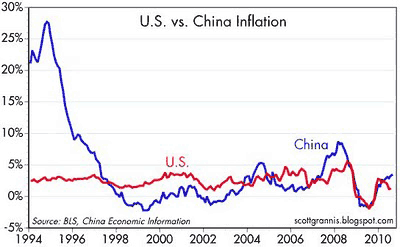

2. Scott writes, “China’s monetary policy has been successful at delivering relatively low and stable inflation: since 1996, in fact, Chinese inflation has been substantially similar to that of the U.S. (see bottom chart above). This fact alone is almost proof that they haven’t been keeping the currency artificially weak. In other words, our price level has risen about the same as the Chinese price level for the past 15 years. If the yuan had been chronically undervalued during that time, then Chinese inflation would most likely have been higher.”

3. And here’s Scott’s main point: “Even if the yuan were chronically “too weak,” what’s the problem anyway? If the Chinese want to sell us cheap goods, that’s to our advantage. True, some manufacturers here might go out of business as a result, but all consumers would benefit. Why should we pursue a policy—forcing the Chinese to appreciate their currency even more than they already have—that would disadvantage every single one of us—because a stronger yuan/weaker dollar would make Chinese imports more expensive—in order to protect a small number of businesses that are forced to compete with Chinese imports?”

MP: Scott’s final point is a key one because it illustrates the special-interest influence on trade policy. If China’s currency policy keeps the U.S. dollar “artificially high” due to “manipulation,” it potentially bestows widespread benefits on millions of American consumers and thousands of American businesses that benefit when they purchase low-priced Chinese imports. Some U.S. companies that compete against Chinese producers might be worse off, but the harm they suffer is far less than the gain to the entire U.S. economy.

Likewise, if China is forced by the U.S. government to appreciate the yuan and depreciate the dollar, only a small group of American producers will benefit from this form of protectionism, but it will be at the expense of harming all consumers and many businesses. And the total gain to the now-protected U.S. producers will be far less than the loss to millions of American consumers and companies who will pay higher prices and be worse off.

Unfortunately, the small, concentrated group of domestic producers (sellers) seeking protectionism through tariffs, quotas or currency re-valuation are usually much better organized, have better lobbyists and more political influence than the millions of disorganized consumers (buyers), so it’s not hard to predict who usually prevails in the political process. But that doesn’t change the economic reality that we’re worse off as a country when a small group of sellers prevails politically and imposes the significant costs of protectionism on millions of consumers. Thanks to Scott Grannis for another great post.

Leave a Reply