Interest rates have three major parts. The first is what is known as the real interest rate, or how much the market is willing to pay you to defer your consumption of goods and services into the future. The second part is an expected rate of inflation. After all, if you want to defer buying a car today so you can buy a better car in the future, it will not help you much if you earn 5% per year on your money if the price of cars goes up at 10% per year. The final part is to compensate you for the risk that you will not get paid back.

If we only look at T-notes and bonds, we can ignore the final part. The government owns the printing press and can always pay you back. Of course if they do too much printing, then we can have an inflation problem, but that is dealt with in the second component, inflation expectations.

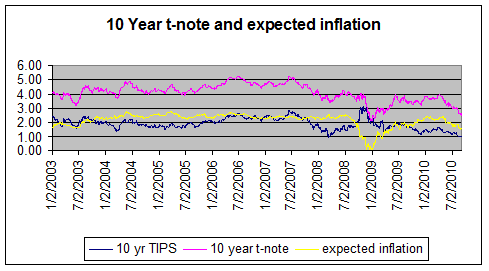

Starting in 2003, the government started to issue TIPS, or inflation-protected T-notes. In addition to being extremely safe investments, they are a great tool for economists. From that point on, we have a direct way of disentangle the real interest rate from the inflation expectations part of the nominal interest rate. Since millions of people are betting their own hard earned cash, this is a much better gauge of what the market thinks inflation will be over until the bond matures than any survey of investors could ever produce.

Why Are Rates So Low?

It is no secret that interest rates right now are very low, but why are they so low? Actually, it is because both real interest rates are low, and because expectations are for inflation to be very tame over the next decade. On Thursday 9/2 (the last day in the St. Louis FRED database) the rate on the nominal 10-year T-note was 2.63%. Since the start of 2003 when the first TIPS were issued, the average rate on the nominal (regular) 10-year note has been 4.07%. The yield on the 10-year TIPS was 1.05%, while its average since introduction is 1.91%.

Subtracting the 1.05% from the 2.63% nominal yield leaves an expected rate of inflation of 1.58% over the next decade. On average, since TIPS were introduced, the average expected rate of inflation has been 2.16%. Clearly the bond market disagrees with those pundits that say that all the deficits we are running today will inevitably lead to higher inflation.

OK, so perhaps having the expected rate of inflation over the coming 10 years 58 basis points lower than average does not sound like a big deal, but the implied inflation rate has only been lower in 181 of the 2000 days since TIPS were first introduced, or 9.05% of the time. It is also more than 1.2 standard deviations below the average.

On the other hand, the implied inflation levels are much higher than they were during the financial meltdown when they were often well below 0.5%, and at one point got down to just 0.04%. Aside from the last few weeks, the only time that 10-year inflation expectations were lower was during the meltdown. Between the October 1, 2008, and May 15, 2009, the expected rate of inflation was below current levels 164 times.

Part of those ultra low levels was probably due to a liquidity premium. The market for TIPS is less liquid than for regular T-notes, but under normal circumstances it remains a very liquid market. Still, the message is that inflation expectations have never been lower, with the exception of a time when there were reasonable fears that we were close to the end of the financial and economic world as we know it.

In its latest communications, including the policy statement that came at the end of their last meeting, the Fed has been indicating that longer-term inflation expectations have been stable. That clearly is not the case, as recently as June the 10-year implied level of inflation was over 2.00%. While “stable” might be a relative term, I don’t think that a 22% decline in expectations in less than three months really meets the every day usage of the term.

However, an even bigger cause of nominal interest rates being so low now — relative to the average of the last almost seven years — is that the real interest rate is extraordinarily low. On Thursday, it stood at just 1.05%, more than 2.1 standard deviations below the average. Put another way, the real interest rate has been below current levels on only 21 days since TIPS were first introduced, or just over 1% of the time. Of those 21 times, 15 have come since August 6th.

This means that there is very little demand for money. Those who claim that high Federal deficits would “crowd out” private demand and send real interest rates soaring have, so far, been proven to be spectacularly wrong. The bond market seems to me to be demanding that the economy grow faster, and it does not mind if the Federal Government borrows more to accomplish that.

If the expectations implied by the spread between TIPS and regular T-note are correct, then if you lock up your money for 10 years, you will be rewarded with only 1.05% per year, or 11.0% more goods and services a decade from now than you would get today. That does not strike me as a particularly good deal. Ten years is a pretty long time to wait for your money.

If Expectations Are Wrong…

If the implied expectations are wrong and inflation is higher than expected, the real return on nominal T-notes could be substantially worse than on TIPS. The inflation expectations could be wrong in the other direction as well, and inflation could come in lower than expected. While that would be good news to holders of long-term T-notes and bonds, it would be very bad news for just about everyone else.

At an expected rate of just 1.58%, there is not a lot of room for inflation to fall further without tipping into outright deflation. Deflation raises the real interest rate for every part of the yield curve. The Fed cannot offset it with lower short-term interest rates, since the rates cannot fall below zero. Money becomes scarce. Not only do prices fall, but so do wages.

If people expect lower prices for goods in the future, why buy today? If you know there is going to be a big sale at Macy’s (M) next weekend on sweaters, do you race out to the mall to buy up sweaters from Macy’s today? That slowdown in spending, especially on durable goods, will further slow down the economy and lead to higher interest rates. Existing debts will become very onerous, and people will work even harder to deleverage their personal balance sheets. It will not work, since the value of their assets will fall faster than they can pay off their debts or build up their savings.

Thus the only really good scenario for investors in regular T-notes is a disaster for everyone else. Even what we normally think of as a bad outcome — rising inflation — would be very bad news for bond investors.

Deflation is the only scenario where the buyer of a regular 10-year T-note will do well over the life of the note. For that to happen, it would require that the Fed just totally abandon its dual mandate to provide stable prices and low unemployment. That would not just be totally incompetent, it would have to entail actual malice on the part of the Federal Reserve towards the U.S. economy. Somehow I just don’t see that happening. The Fed has tools at its disposal to prevent deflation.

For starters, it could simply buy up long-term T-notes. As it does so, it is the equivalent of turning on the printing presses and increasing the money supply. Instead of paying interest on excess reserves, it could encourage (force?) banks to lend by charging a small fee on excess reserves. It should not be hard for a central banker to create inflation if they want to.

What Can Be Done

The most direct way to play the likely rise in T-note rates is through the use of ETF’s like the ProShares UltraShort 20+ Year (TBT). Another alternative is simply to buy solid dividend-paying stocks with solid balance sheets. There are lots of firms out there that have current dividend yields higher than the 10-year note is paying (see “Paying Dividends” for some ideas).

One thing is certain: if you invest $1000 in a 10-year T-note at 2.70%, you will get $27 a year, no more and no less, as well as your $1000 back a decade from now. If you invest the same $1000 in a stock yielding 2.70%, you also get $27 this year, but there is a very good chance that you will get more than $27 next year, and still more the year after that. While there is a risk that the dividend gets cut in any given company, the risk of a diversified portfolio of stocks with dividends averaging 2.70% will see the total amount of dividends decline over the next decade is pretty remote.

It has been more than 50 years (except for the immediate meltdown period) since you could easily find a diversified portfolio of stocks that yielded more than the 10-year note. That appears to me to be the makings of a historic opportunity to either buy stocks or short bonds (or both). However, with the economy on the weak side, stick to strong well-capitalized firms, with good balance sheets (deflation is a big negative to firms with a lot of debt) and preferably firms that pay a nice dividend.

Leave a Reply