Here’s how I’m tempted to summarize today’s release of the August employment report from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics: more of the same. That theme fits nicely with comments this morning from Atlanta Fed President Dennis Lockhart, in a speech at East Tennessee State University. Here he calls for a little perspective:

“Some commentators are reading recent economic data as suggesting the onset of a second recession and deflationary cycle. Quite naturally, business people and consumers aren’t sure what to believe.

“At the last meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) in Washington, the committee made a decision that has been widely interpreted as signaling declining confidence in the strength and sustainability of the recovery….

“In my remarks today, I will provide a less alarmist interpretation of recent economic information and the Fed’s recent policy decision. I will argue that, generally speaking, there was too much optimism in the early months and quarters of the recovery and now there may be excessive pessimism.”

One point is that recoveries are not generally linear affairs:

“Growth at the end of last year and early part of this year was stronger than I anticipated while economic activity in the second and third quarters seems weaker than I expected.

“But such ups and downs are not unusual during a recovery. A little history: following the 2001 recession, gross domestic product (GDP) grew at the annualized rate of 3.5 percent in early 2002. Growth then decelerated to about 2 percent for the next two quarters then fell to almost zero in the fourth quarter. Entering 2003, growth edged up to a little over 1.5 percent and then accelerated from there to a sustained period of relatively strong growth for two years.”

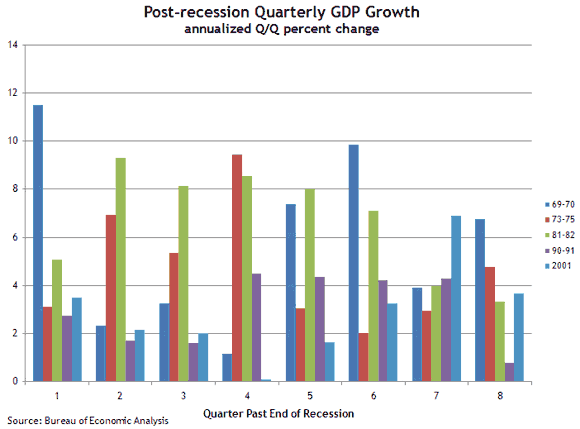

Here’s a look at a little more history:

Even in the rapid-growth, pre-1990 recoveries, there was generally a quarter or two of growth that underperformed. In the first three months of 1971, the first full quarter after the 1969–70 recession, growth came scorching out of the gate at 11.5 percent. But that was followed by growth rates of 2.29, 3.23, and 1.12 percent. Though the early expansion after the inflation-breaking 1981–82 contraction was robust throughout, the 1973–75 recession softened noticeably in the second year of expansion, with quarterly growth falling just below 2 percent at one point.

But the better benchmarks will likely prove to be the slower-growth, low-employment recoveries post-1990. In addition to the 2001 experience noted by President Lockhart, the expansion that followed the 1990–91 recession stumbled along with quarterly growth rates of 2.7, 1.69, and 1.58 percent, before picking up to above-potential growth rates. Despite that, the eighth quarter after that recession’s end clocked in at an anemic 0.75 percent.

What is more important is that there is a reasonably good explanation for why we might have hit a soft patch:

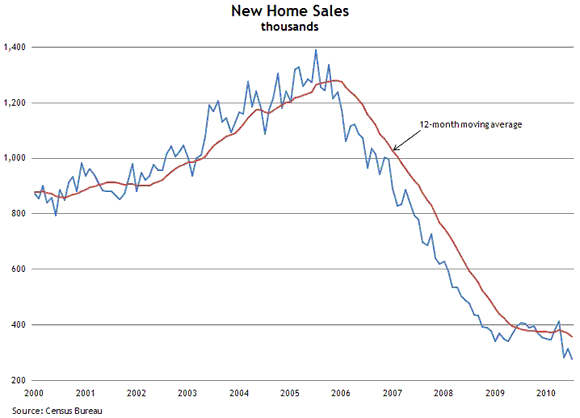

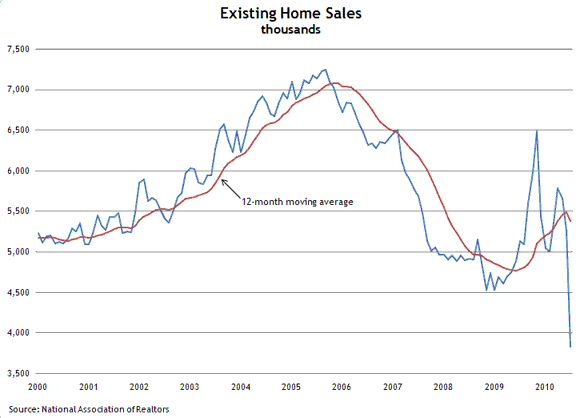

“Looking at the 2009–2010 recovery, it seems clear that some of the early strength was promoted by policies that pulled forward spending from the second and third quarters of this year. The recent sharp decline in housing-related indicators following the expiration of homebuyer tax credits is the most obvious example of this effect.”

Comparing monthly home sales patterns with year-over-year performance really does illustrate the point:

Essentially, President Lockhart’s is a simple message: don’t ignore the short-term data, but be careful with getting too carried away with it as well.

“Simply stated, I was expecting a relatively modest recovery, a pattern typical following the kind of financial crisis we experienced….

“Melding all this mixed information, my basic view of the economy has not changed, but my perception of risks has shifted somewhat to the downside.

“It was this perspective—a perspective I’d characterize as moderate optimism tempered by acknowledgement of weaker conditions and greater downside risk—that I carried into the last FOMC meeting on August 10.”

And with respect to that meeting, here is the main policy point:

“At the last meeting there were two important considerations as I saw it. First, as already discussed, some economic data came in weaker than expected, shifting the balance of risks to slower growth in the near term and further disinflation. Second, the Fed’s holdings of MBS were projected to decline faster than previously thought because lower rates were generating heavy mortgage prepayments and refinancings.

“So, in the context of a softening economy, the FOMC was confronted with the prospect of unintended withdrawal of support for the recovery through a decline in the level of liquidity provided to the economy….

“That is how I interpret the decision announced following the August meeting—a small tactical change designed to preserve the level of liquidity provided to the system. I supported the committee’s decision, but I do not view it as a fundamental change of outlook or strategy. I do not believe this change necessarily heralds the beginning of a period of further expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet. Nor do I think the decision precludes a return to a policy of allowing the balance sheet to shrink on its own.

“I think the decision has been over-interpreted in some quarters.”

I’ll close with that thought by President Lockhart. Have a nice, long holiday weekend.

Leave a Reply