You are a (small) open economy. If you borrow, you are a net importer of goods and services–you run a trade deficit. You may want to run a trade deficit for a long time, but ultimately, creditors will expect you to pay back what you owe. To make good on your promises, you will have to run a trade surplus at some point in the future. (Alternatively, you may wish to default, but let me ignore this possibility for now).

You are a (small) open economy. If you borrow, you are a net importer of goods and services–you run a trade deficit. You may want to run a trade deficit for a long time, but ultimately, creditors will expect you to pay back what you owe. To make good on your promises, you will have to run a trade surplus at some point in the future. (Alternatively, you may wish to default, but let me ignore this possibility for now).

Setting the problem of default aside, the example above highlights a key property of what economists call an intertemporal budget constraint. Fancy words, but all it really means is that if you borrow today, you will have to pay back tomorrow. Applying the same principle to nations, it means that a trade deficit today will have to be matched by a trade surplus tomorrow. This principle suggests that “imbalances” in a country’s international trade account are expected to be “temporary” (kind of like the “temporary” income tax measure of 1913?).

Sounds like good ol’ common sense. And it probably applies to most countries. Except, maybe, for big and powerful economies, like the USA?

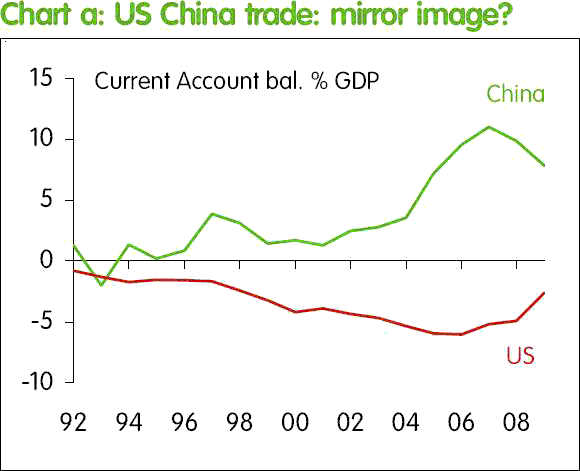

The US has had a growing trade deficit for the better part of the last 20 years; see Chart a (source). (The trend appears to have reversed a bit during the recent recession, but the most recent data show a move back to pre-recession levels.) For the most part, the flip side of the US trade deficit corresponds to a Chinese trade surplus. In short, the Chinese are working their pants off producing stuff and then exporting it to the US. In return, the US sends small denomination paper notes called USD (or US treasuries, representing promises to deliver future USD).

There is, as far as I can tell, no consensus on what is driving these interesting trade flows. Almost everyone seems to think that this imbalance is bad. Bad, bad, bad. (I mean, how can imbalance ever be good?). Someone must be getting screwed. Some believe that the American worker is the victim (see how clever those Chinese are…they have attained a full employment sweatshop equilibrium!). Others question the wisdom of Chinese trade policy (let’s see, they ship us goods, we ship them paper, they ship us goods, we ship them more paper…hmm).

Well, maybe they’re right. But before we capitulate to consensus opinion, I want to explore another possibility. Could it be that this exchange of goods for assets is mutually beneficial for the countries involved? (I abstract, of course, from the inevitable mix of winners and losers that are produced with any trade liberalization). And if so, how might this be?

In my previous post, I pointed to Ricardo Caballero’s “Asset-Shortage Hypothesis” as one way to understand the “global imbalance” phenomenon. The basic idea is that there is a world “shortage” of assets that are perceived to be good collateral objects and/or good stores of value. The source of these shortages may ultimately be related to cross-country differences in property rights regimes (relatedly, the degree of financial development). If so, then local governments should address the problem directly. But if they do not, or if it takes time, then local agents may exhibit a demand for foreign-produced assets, like US dollars and US treasuries. Of course, to acquire such assets they will have to purchase them with exports of goods and services. This is not crazy; after all, there is also a huge domestic appetite for US treasuries in local repo and credit derivatives markets.

And so, perhaps countries like China simply find the USD useful and are therefore willing to pay for it (with exports). The US values foreign produce and so imports it (by exporting USD). Both countries experience gains from this trade.

A Simple Model

Let me describe one way to formalize the argument above. Consider a world consisting of two economies; a “domestic” economy and a “foreign” economy. Each country is populated by 2-period-lived overlapping generations (and an initial old generation, that lives for one period only). I use an OLG model for its analytical tractability–nothing I have to say here depends on the OLG structure, so don’t get hung up on interpreting the model structure too literally.

The young in each country have a nonstorable endowment of output, y. The young derive a “little bit” of utility from consuming their endowment; but they would really rather consume output when they are old (i.e., they really value the output produced by the next generation of young people). This OLG structure is useful because it models a complete lack of double coincidence of wants among agents (and so, bilateral quid pro quo barter in goods is ruled out).

For the purpose of exposition, I take the asset shortage friction to an extreme. In particular, assume that there is only one asset, a fiat object called the USD, which is produced only in the domestic economy. For simplicity, I assume that the aggregate nominal stock of USD M remains fixed forever (it is easy to relax this assumption). Let pt denote the price of output at date t measured in USD (i.e., the price-level).

I assume that the domestic population remains constant over time (normalize the population of domestic young agents to unity). I assume that the foreign population grows over time. Let Nt denote the population of foreign young agents at date t and assume that Nt+1 = nNt where n > 1 denotes the (gross) foreign population growth rate.

Note: we need not interpret N literally as population. It is simply a parameter that will index the foreign demand for USD. Likewise, n represents the rate of growth in that demand. A financial liberalization in the foreign sector, or some other innovation, can be modeled as a change in these parameters.

Autarky

Things are grim in the foreign sector; there is no trade at all. The young simply consume their endowment (they derive little pleasure from this) and the old go wanting. This is also an equilibrium outcome in the domestic economy. But there is also another equilibrium–one in which the fiat object is valued. In this equilibrium, the young sell their output to the old for USD (we endow the initial old with M). Hence, pt y = M for all t > 1. The young use the money accumulated in this manner to purchase the good they really desire (next period output). In this manner, money circulates as it facilitates welfare-improving trades. The (stationary) equilibrium price-level is constant over time,

p = M / y. (Note: this is an example of a welfare-improving asset price bubble — a result that commonly emerges in environments with asset-shortages).

Free trade

Well, if an asset price bubble (defined as an asset that trades above its fundamental value) is good for the domestic economy, might it also be good for the foreign economy (hence good for the world economy)? The answer is yes.

Imagine that trade is suddenly allowed to occur between these two economies at date 1. I like to think of the foreign sector at this point as being small relative to the domestic sector, so that 0 < N1 << 1. Of course, since n >1, the foreign sector is growing faster than the domestic economy. Left unchecked, this implies that the foreign sector will eventually swamp the domestic economy in size.

The date t foreign young agents will want to acquire USD. So they export their output y to the domestic economy for USD. The aggregate foreign demand for USD, measured in units of output, is Nt y. The domestic demand for USD is simply y. Hence, the relevant market-clearing condition at date t is now given by:

[1] M = (1 + Nt )pt y for all t = 1, 2, 3, …

At date 1, following the trade liberalization, the price-level jumps down (reflecting the sudden appearance of a foreign demand for USD). That is, equation [1] implies p1 = M / [ (1 + N1 )y ] < M / y (the domestic price-level in autarky).

Since condition [1] must hold at all dates, it must also hold in period t + 1. Hence, M = (1 + Nt+1 )pt+1 y . This latter equation, together with [1], allows us to derive an expression for the equilibrium inflation rate:

[2] pt+1 / pt = [ 1 + Nt ] / [ 1 + nNt ] < 1 (since n > 1 )

Condition [2] implies that the trade liberalization induces a deflation (a falling price level). In the limit, the deflation rate (the inverse of the inflation rate) approaches n from below. (Keep in mind that I am keeping the nominal supply of debt fixed in this experiment). Deflation in this model is neither good nor bad; it simply reflects the growing demand for USD and implies that the purchasing power of money rises over time.

Let me now examine trade flows. At date 1, the foreign young demand F1 = p1 N1 y dollars. Since p1 = M / [ (1 + N1 ) y ], this implies that the initial foreign dollar demand is given by:

[3] F1 = [ N1 / (1 + N1) ] M

That is, they will demand a fraction of the outstanding money supply (which is initially in the hands of the date 1 domestic old agents). To acquire these F1 dollars, they must export N1 y units of output to the domestic economy (to be consumed by the domestic old). The result is a trade balance surplus for the foreign economy and an offsetting trade balance deficit for the domestic economy.

As an aside, it is of some interest to note what happens next in the case of n = 1. What happens is that all international trade ceases. The USD acquired by foreigners in the initial period simply continue to circulate in the foreign economy as currency. Absent any changes, the domestic economy will forever be a debtor nation; and the foreign economy will forever be a creditor nation. On the other hand, it’s not like the domestic economy “owes” the foreign economy anything. They did, after all, export USD, an asset that foreigners evidently find useful.

Let us now return to the case of n > 1. This case is even more interesting, because it implies that trade will continue into the indefinite future.

At date 2, the foreign demand for USD grows (in real terms) by (n – 1)N1 y. At date 3, this foreign demand will grow by (n -1)n N1 y. At date 4, it will grow by (n -1) n2 N1 y, and so on. For any arbitrary date t > 1, the additional real foreign demand for USD will grow by:

[4] xt = (n – 1) nt-2 N1 y

Assuming that the foreign sector keeps its borders open to international trade, equation [4] describes the flow of exports to the domestic economy in each period t. What is remarkable here, I think, is the theoretical possibility that these exports continue in perpetuity — there the possibility of persistent and growing global imbalances in this world economy. Of course, going the other way are exports of USD. In the equilibrium under consideration, domestic residents peel away ever thinner slices of their remaining USD holdings and ship them to the foreign economy for imported goods. These thinner slices are able to buy the available imports because of the deflation, which increases the purchasing power of USD over time.

It would be of some interest, of course, to extend the model in a variety of ways. We might let the domestic government alter the supply of its assets (collecting seigniorage from the rest of the world). We might imagine a date at which the foreign demand for USD reverses, or even collapses. Etc., etc.

Conclusions

It’s important that we not get carried away with a simple model, or ascribe too much importance to the Asset Shortage Hypothesis. There are almost certainly many other factors contributing to the phenomena we see developing around us.

Nevertheless, the hypothesis — and the way in which I formalized it here — may be an important contributing factor to the “global imbalances” phenomenon. If it is, then perhaps this is one way to interpret low US inflation rates (as opposed to a competing hypothesis, which explains inflation as the product of “output gaps”). Moreover, as the analysis above makes clear, global imbalances and asset price bubbles are not necessarily a “bad” thing. This does not, of course, mean that we can safely ignore these phenomena as they develop over time. Things might change and bubbles can burst. These are contingencies that policymakers need to plan for.

Leave a Reply