Two features of the current recession – its association with a deep financial crisis and its highly synchronised nature – suggest that it is likely to be unusually severe and followed by a weaker-than-average recovery. Current and near- term policy responses are the key to understand how the recession will evolve this time.

The advanced economies are experiencing a financial crisis and a highly synchronised recession, which is a very rare combination of events. This raises three questions; Are recessions and recoveries associated with financial crises different from others? What are the main features of globally synchronised recessions? Can countercyclical policies help to shorten recessions and strengthen recoveries?

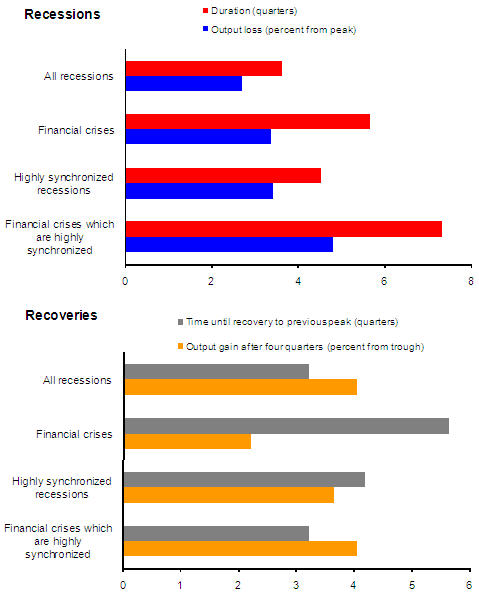

Reinhart and Rogoff (2008) argue that the crises that come with financial crises are different, a point Carmen Reinhart made in months ago in Vox column. But the Reinhart and Rogoff (2008) does not focus specifically on the combination of crisis factors at play today. Recent research we have undertaken redresses this. We examine the dynamics of business cycles in 21 advanced economies over the past half century. Excluding current recessions, a total of 122 recessions were identified in the sample. Recessions in the advanced countries are distinctly shallow and brief (see chart). Recoveries from such recessions to pre-crisis peaks are typically strong and quick, reflecting in part the presence of a bounce-back effect which, in turn, is driven by technological progress, population growth, and macroeconomic policies (IMF 2009).

Recessions and financial crises

Recessions associated with financial crises tend to be severe and recoveries from such recessions are typically slow. It takes almost 3 years to return to the pre-recession output level—which is twice the time it takes to recover from other recessions. Financial crises typically follow periods of rapid expansion in lending and strong increases in asset prices. Recoveries from these recessions are often held back by weak private demand and credit, reflecting, in part, households’ attempts to increase saving rates to restore balance sheets. They are typically led by improvements in net trade, following exchange rate depreciations and falls in unit costs.

Highly synchronised recessions

Similarly, globally synchronised recessions are longer and deeper than others, and their recoveries are sluggish. Excluding the present, there have been three episodes of highly synchronised recessions over the past fifty years; 1975, 1980 and 1992. Recoveries are usually sluggish, owing to weak external demand, especially if the US is also in recession. While historically rare, the combination of financial crisis and a globally synchronised downturn typically results in an unusually severe and long lasting recession, with a weaker-than-average recovery. These recessions last almost 2 years and it takes a total of 3½ years for output to return to its pre-recession level.

Countercyclical policies do work!

Countercyclical macroeconomic policies can be helpful in ending recessions and strengthening recoveries. Monetary policy has typically played an important role in ending recessions. But its impact is not statistically significant during financial crises—this could be a result of the stress experienced by the financial sector, which hampers the effectiveness of the interest-rate and bank-lending channels of the transmission mechanism of monetary policy. Fiscal policy seems to be more helpful in these episodes, consistent with evidence that fiscal policy is more effective when economic agents face tighter liquidity constraints. Fiscal stimulus is also associated with stronger recoveries; however, the impact of fiscal policy on the strength of the recovery is found to be smaller for economies that have higher levels of public debt.

Conclusion

The implications from our analysis for the current situation are, indeed, sobering. The current recessions, which are highly synchronised and associated with a deep financial crisis, are likely to be long and severe and their recoveries sluggish. Indeed, there are clear signs that the current recessions are more severe and longer than usual.

Yet, aggressive monetary and fiscal polices could make a difference. In particular, expansive fiscal policies can make a significant contribution to reducing the duration of the current recessions and strengthening their recovery. Given the highly synchronised nature of the current recessions, there is a need for global fiscal stimulus, provided by a broad range of countries. Such stimulus is being implemented and will reach roughly 2% of GDP in 2009 relative to 2007 in the G20 countries. Countries with room for policy manoeuvre will likely have to maintain or even expand fiscal policy support in 2010, given the difficult outlook for activity. Preparing early is essential so that expansionary measures kick in on time to slow the large rise in unemployment that can be expected over the next couple of years.

References

Claessens, Stijn, M. Ayhan Kose, and Marco E. Terrones (2009). “Global financial crisis: How long? How deep?” 7 October 2008, VoxEU column.

Claessens, Stijn, M. Ayhan Kose, and Marco E. Terrones, 2008, “What Happens During Recessions, Crunches and Bust?” IMF Working Paper 08/274.

International Monetary Fund, 2009, “From Recession to Recovery: How Soon and How Strong?”, World Economic Outlook, Chapter 3.

Reinhart, Carmen (2009). “The economic and fiscal consequences of financial crises”, 26 January 2009, VoxEU column.

Reinhart, Carmen and Kenneth Rogoff, 2008, “Banking Crises: An Equal Opportunity Menace”, NBER Working Paper No. 14587.

![]()

Leave a Reply