Financial stress reached unprecedented levels in 2008. This column presents a new IMF financial stress index and puts the current crisis into historical perspective. It also shows that bank-lending linkages appear to be the main driver of the transmission of stress. International financial integration brings both opportunities for growth and risks of contagion.

Financial stress in advanced and emerging economies reached unprecedented levels in 2008. After an initial period of resilience, the turmoil hit emerging economies hard. With the scale of the crisis growing, a rich debate about its similarities with past global crises and its implications for emerging economies has ensued (e.g. Eichengreen and O’Rourke 2009, Calvo and Loo-Kung 2008). However, measuring the intensity and the transmission of stress poses an empirical challenge.

Measuring financial stress

Academic studies have largely relied on historical narratives of well-known systemic banking crises, when bank capital was eroded, lending disrupted, and public intervention required (e.g., Eichengreen, Rose, and Wyplosz, 1996; Laeven and Valencia 2008; Reinhart and Rogoff 2008). In contrast, episodes of financial stress in securities markets have largely been passed over, especially those episodes that involved multiple emerging economies. Previous studies also mostly viewed variables as binary – either no crisis or crisis – and hence were not able to compare the intensity of stress and the degree of transmission between countries.

To complement the indicators used in the literature, we have devised a new financial stress index for emerging economies, which we presented in the recent IMF World Economic Outlook study (R. Balakrishnan et. al. 2009). This index builds on a similar index for advanced economies (Cardarelli, Elekdag, and Lall, 2009) and captures the intensity of financial stress in a broad cross-section of the financial sector.

The financial stress index is composed of four market-based price indicators and an exchange market pressure index. Each component is de-meaned, scaled by the inverse of its standard deviation, and then added together to form the index. This equal-variance-weighted combination has the advantage that large fluctuations in one component do not dominate the overall index. The additive feature also allows for a straightforward decomposition into contributions by sub-index. Dates of peaks and troughs of the index are robust to other weighting schemes, including, for example, those based on principal components analysis.

The index is available for 18 emerging economies from 1997 to 2009 on a monthly basis and captures the most important episodes of financial stress experienced by emerging economies as identified in academic studies.

Putting the crisis in perspective

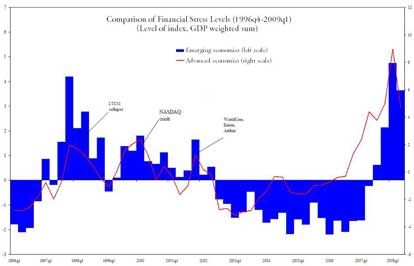

Figure 1. Comparing financial stress levels

According to the advanced and emerging economy indices, global financial stress was at record highs at year-end 2008 (Figure 1). Virtually all advanced economies experienced financial stress at unprecedented levels (the data for this index go back to 1980) and the crisis has already lasted longer than any crisis since 1980. In emerging economies, the intensity of stress in 2008 surpassed levels seen during the Asian crisis. High stress was recorded in all major emerging regions and affected all parts of the financial sector (securities, exchange markets and banks). There was some tapering off in early 2009, but overall stress is still very high.

Transmission of stress: How strong and how fast?

Our study finds that stress in emerging economies typically increases almost one-for-one with stress in advanced economies. This result is based on a two-stage estimation process (Forbes and Chinn 2004) using monthly data and a panel data analysis using annual data. Transmission is rapid and occurs within one or two months after advanced economies are in financial stress.

That said, there has clearly been regional variation during the current crisis. Emerging Europe was hit especially hard, while economies in Latin America weathered the first wave of stress fairly well. This variation is mainly accounted for by the strength of financial linkages with advanced economies. Countries with higher foreign liabilities – measured by bank lending, portfolio investments, and FDI as a percentage of destination country GDP – experienced stronger transmission.

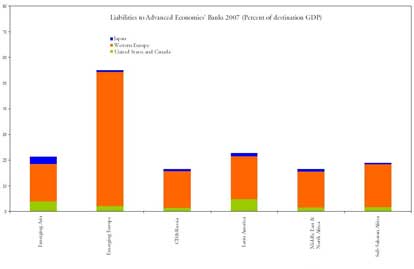

The twist in the current crisis is that bank-lending linkages appear to be the main driver, rather than the more mobile portfolio investment links that drove the Asian crisis. Since the mid-1990s, Western European banks have dominated bank-lending flows. Emerging Europe stands out as the largest recipient (Figure 2). Using an econometric model for stress transmission, we find that an increase in bank liabilities to Western Europe from 15% to 50% of GDP (roughly the difference between Emerging Europe and other emerging regions) doubles the strength of stress transmission. It is no surprise therefore that Emerging Europe was the first emerging market region to be hit hard by the crisis.

Figure 2. Liabilities to advanced economies’ banks, 2007

Implications for capital flows

The likely trajectory for capital flows – based on historical evidence – is a slow and protracted recovery. The reason is the key role of banking-sector stress in the current crisis. Evidence from past systemic banking crises in advanced economies (the US in the 1980s and Japan in the 1990s) shows that the decline in capital flows to emerging economies tends to be sizeable. Since then, banking-sector globalisation has continued, and the risks of large-scale deleveraging associated with common lender effects have risen. Given their large share of external financing through banks, a number of Emerging European economies might be severely affected by a drought of private capital inflows.

What can be done?

An important question is whether countries can protect themselves against the transmission of a large financial shock in advanced economies. The answer is mixed. Reducing individual country vulnerabilities (current account and fiscal balances) does not insulate countries from the transmission of financial stress. However, a solid track record allows them to implement a stronger domestic policy response and potentially experience a more rapid recovery once the crisis in investor countries abates.

The bottom line is that while international financial integration brings opportunities for future growth, it also comes with risks for emerging economies and a possibility of contagion from advanced economies. This underlines the need not only for strong policy frameworks in emerging economies but also the need for access to multilateral insurance systems during global crises.

References

R. Balakrishnan, S. Danninger, S. Elekdag and I. Tytell (2009) “How Linkages Fuel the Fire: The Transmission of Financial Stress from Advanced to Emerging Economies” World Economic Outlook, Chapter 4, April (IMF Research Department).

Calvo Guillermo and Rudy Loo-Kung (2008) “Rapid and large liquidity funding for emerging markets”, 10 December 2008, VoxEU.org

Cardarelli, Roberto, Selim Elekdag, and Subir Lall, (2009) , “Financial Stress, Downturns, and Recoveries”,IMF Working Paper (Washington: International Monetary Fund), forthcoming.

Eichengreen, B. and K.H. O’Rourke. (2009) “A Tale of Two Depressions”, VoxEU.org

Eichengreen, Barry, Andrew Rose, and Charles Wyplosz, (1996), “Contagious Currency Crises”, NBER Working Paper 5681, July, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: National Bureau of Economic Research).

Forbes, Kristin, and Menzie D. Chinn, (2004), “A Decomposition of Global Linkages in Financial Markets Over Time”, The Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 86, Issue 3, pp. 703–22, August.

Laeven, Luc, and Fabian Valencia, (2008), “Systemic Banking Crises: A New Database”, IMF Working Paper 08/224.

![]()

Leave a Reply