The US trade deficit rose on the back of an import surge. From Bloomberg:

The trade deficit in the U.S. unexpectedly widened in May to the highest level in 18 months as a gain in imports outpaced an increase in shipments abroad.

The gap expanded 4.8 percent to $42.3 billion as U.S. companies imported more automobiles and consumer goods, Commerce Department figures showed today in Washington. The deficit was projected to narrow to $39 billion, according to the median forecast in a Bloomberg News survey. Imports and exports rose to the highest level since 2008.

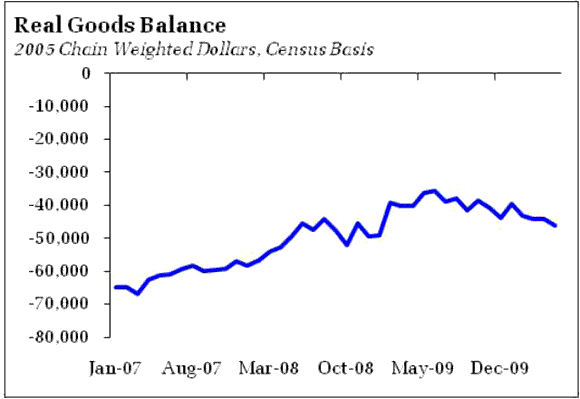

As noted by Calculated Risk, you can’t blame this one on oil – the petroleum deficit actually improved in both real and nominal terms. Overall, the goods deficit widened in real terms as well:

International trade looks likely to detract from overall growth for a fourth consecutive quarter. So much for the rebalancing. The Obama Administration can continue to prattle on about export growth, but trade is a game with two sides – if you lose more jobs to imports than you gain from exports, doubling exports is not a particularly effective stimulus.

It is important to recognize that as the global activity rebounded from the depths of the recession, the improvement in the US external balance came to a screeching halt and then reversal. The reason is simple – we have offshored so much production capacity that it becomes impossible to grow without an expansion of the trade deficit. Policymakers have not allowed for sufficient currency adjustment or relative growth differentials for any other outcome to occur. Indeed, the picture is likely to deteriorate further in the months ahead:

The increase in trade flows shows how the global expansion lifted sales at companies like Alcoa Inc. Export growth may cool in coming months as the fallout from the European debt crisis limits overseas demand and a recent strengthening of the dollar makes American goods less competitive.

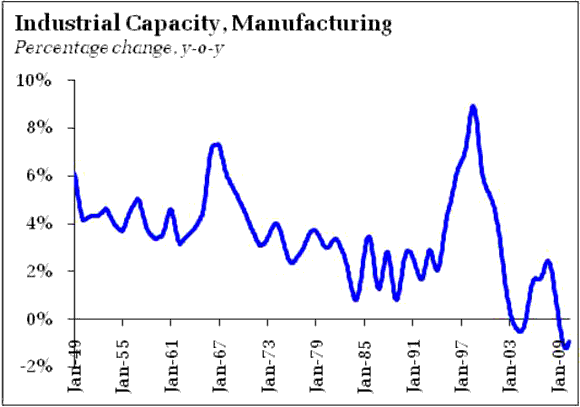

The challenges of addressing what is a structural trade deficit are magnified when one recognizes that manufacturing capacity is now shrinking in the US:

This makes the US more reliant on foreign production in the future, and also raises questions about the ability of the US economy to generate the output necessary to return those goods at some point in the future.

Also, this is relevant to the corporate cash debate. Are firms sitting on cash because of weak demand or distress over the implication of deficit spending? I find myself in the “weak demand” camp, but with a twist: When firms begin to deploy that capital, where will they put it go? To expanding capacity in the US? Or China? And will China ultimately just absorb the capital inflow, swelling currency reserves further?

What I fear is the latter. As production facilities in the US depreciate, firms are looking to replace that capacity with Chinese production. The owner of a chemical manufacturing firm explained it to me quite succinctly: When all of his customers moved to China, he really had little choice but to do the same. The tiny – although officially exalted – renminbi adjustment does nothing to change this trend. Simply put, only very large currency adjustments would be sufficient to deter US firms from continuing to pursue a China strategy.

On can continue to hold the fantasy that an army of well paid massage therapists or clerks at Trader Joe’s can offset the impact of not just absolute declines in manufacturing employment but also absolute declines in manufacturing capacity. Holding onto that fantasy is much easier than recognizing that maybe, just maybe, the economic consequences of trade with China have been much more severe and long lasting than officialdom is willing to acknowledge.

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply