Roughly half of U.S. workers are employed at firms with fewer than 500 employees, and about 90 percent of U.S. firms have fewer than 20 employees. While estimates vary, small businesses are also credited with creating the lion’s share of net new jobs. Small businesses are, in total, a big deal. Thus, it is no surprise that there is congressional debate going on about how to best aid small businesses and promote job growth. Many people have noted the decline in small business lending during the recession, and some have suggested proposals to give incentives to banks to increase their small business portfolios. But is a lack of willingness to lend to small businesses really what’s behind the decline in small business lending? Or is it the lack of creditworthy demand resulting from the effects of the recession and housing market distress?

Economists often face such identification dilemmas, situations in which we would like to know whether supply or demand is the driving factor behind changes within a market. Additional data can often help solve the problem. In this case we might want to know about all of the loans applied for by small businesses, whether the loans were granted and at what rates, and specific information on loan quality and collateral. Alas, such data are not available. In fact, the Congressional Oversight Panel in a recent report recommends that the U.S. Treasury and other regulators “establish a rigorous data collection system or survey that examines small business finance” and notes that “the lack of timely and consistent data has significantly hampered efforts to approach and address the crisis.”

We at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta have also noted the paucity of data in this area and have begun a series of small business credit surveys. Leveraging the contacts in our Regional Economic Information Network (REIN), we polled 311 small businesses in the states of the Sixth District (Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi and Tennessee) on their credit experiences and future plans. While the survey is not a stratified random sample and so should not be viewed as a statistical representation of small business firms in the Sixth District, we believe the results are informative.

Indeed, the results of our April 2010 survey suggest that demand-side factors may be the driving force behind lower levels of small business credit. To be sure, when asked about the recent obstacles to accessing credit, some firms (34 firms, or 11 percent of our sample) cited banks’ unwillingness to lend, but many more firms cited factors that may reflect low credit quality on the part of prospective borrowers. For example, 32 percent of firms cited a decline in sales over the past two years as an obstacle, 19 percent cited a high level of outstanding business or personal debt, 10 percent cited a less than stellar credit score, and 112 firms (32 percent) report no recent obstacles to credit. Perhaps not surprisingly, outside of the troubled construction and real estate industries, close to half the firms polled (46 percent) do not believe there are any obstacles while only 9 percent report unwillingness on the part of banks.

These opinions are reinforced by responses detailing the firms’ decisions to seek or not seek credit and the outcomes of submitted credit applications.

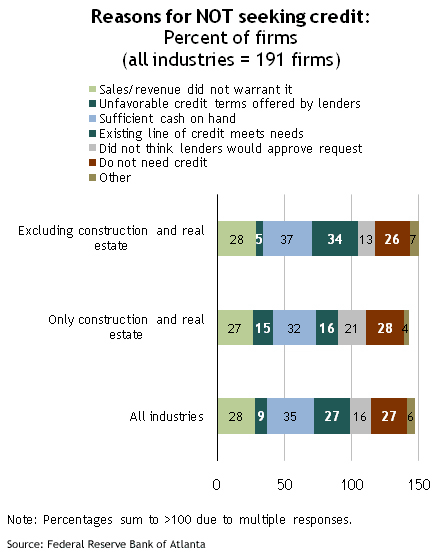

Of the 191 firms that did not seek credit in the past three months, 131 (69 percent) report that they either had sufficient cash on hand, did not have the sales/revenues to warrant additional debt, or did not need credit. (Note the percentages in the chart above reflect multiple responses by firms.) These responses likely reflect both the impact of the recession on the revenues of small firms as well as precautionary/prudent cash management.

The administration has recently sent draft legislation to Congress for a supply-side program—the Small Business Lending Fund (SBLF)—to address the funding needs of small businesses. The congressional oversight report raises a good question about the potential effectiveness of supply-side programs:

“A small business loan is, at its heart, a contract between two parties: a bank that is willing and able to lend, and a business that is creditworthy and in need of a loan. Due to the recession, relatively few small businesses now fit that description. To the extent that contraction in small business lending reflects a shortfall of demand rather than of supply, any supply-side solution will fail to gain traction.”

That said, one way that a supply-side program like SBLF would make sense, even if low demand is the force driving lower lending rates, is if there are high-quality borrowers that are not applying for credit merely because they anticipate that they will be denied. We could term these firms “discouraged borrowers,” to co-opt a term from labor markets (i.e., discouraged workers).

If a program increased the perceived probability of approval, either by increasing approval rates via a subsidization of small business lending or merely by changing borrower beliefs, more high-quality, productive loans would be made.

Just how many discouraged borrowers are out there? The chart above illustrates that, indeed, 16 percent of all of our responding firms and 21 percent of construction and real estate firms might fall into this category. I add “might” because the anticipation of a denial may well be accurate but based on a lack of creditworthiness and not the irrational or inefficient behavior of banks. Digging into our results, we find that 35 percent of the firms who did not seek credit because of the anticipation of a denial also cited “not enough sales,” indicating that a denial would likely have reflected underlying loan quality.

In the labor market, so-called “discouraged workers” flow back into the labor force when they perceive that the probability of finding an acceptable job has increased enough to make searching for work, and working, attractive again. We should expect so-called “discouraged borrowers” to do the same. That’s because if they don’t, the likely alternatives for them, at some point, would be to sell the business or go out of business. It seems unlikely that, facing such alternatives, a “discouraged” firm would not attempt to access credit. The responses of firms in our sample are consistent with this logic; 55 percent of those who did not seek credit in the past three months because of the anticipation of a denial indicated that they plan to seek credit in the next six months.

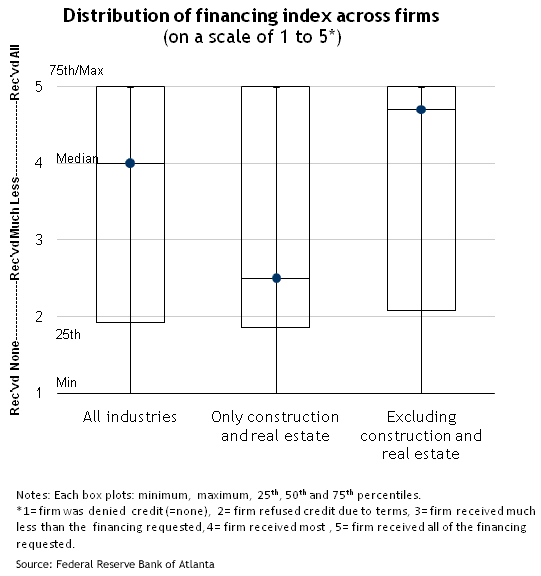

Our results also provide some interesting data on an assumption underlying the policy debate: that those small businesses are credit constrained. Of the 117 firms in the survey that that sought credit during the previous three months, the following chart illustrates the extent to which these firms met their financing needs.

Based on firm reports of the credit channel applications submitted in the previous three months, we created a financing index value for each firm. Firms that were denied on all of their credit applications have a financing index equal to 1, while firms that received all of the funding requested have an index level of 5. Index levels between 1 and 5 indicate, from lesser to greater, the extent to which their applications were successful. In the chart we plot data on the financing index levels of all firms in our sample and then split according to whether the firm is in construction and real estate. Among construction and real estate firms, 50 percent of firms had an index below 2.5, suggesting most did not get their financing requests meet. In contrast, the median index value of 4.7 for all other firms suggests that most of these firm were able to obtain all or most of the credit they requested. This difference between real estate–related firms and others is really not surprising given that the housing sector was at the heart of the financial crisis and recession. But it does suggest that more work needs to be done to analyze the industry-specific funding constraints among small businesses.

Leave a Reply