Liquidity is one of the key selling points for exchange-traded funds (ETFs), but the Dow Jones “flash crash” of May 6 shows how that supposed advantage can turn into a huge liability for investors.

A report this week from the SEC and the Commodities Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) found that ETFs accounted for the overwhelming majority of securities that fell at least 60 percent that day. Many of those ETFs fell all the way to $0.01 per share during trading.

The SEC-CFTC report blames a lack of liquidity for the crash. Many registered investment advisors, brokers and institutional investors use ETFs in their hedging strategies, but this backfired when a spike in volatility caused a stampede of sellers that crushed prices.

I don’t believe ETFs caused the “flash crash” but the events of May 6 give investors a good reason to look closely under the hood of ETFs. When they do, they might be surprised by what they find.

Research shows that the tradability of ETFs can actually be a costly curse in terms of real returns.

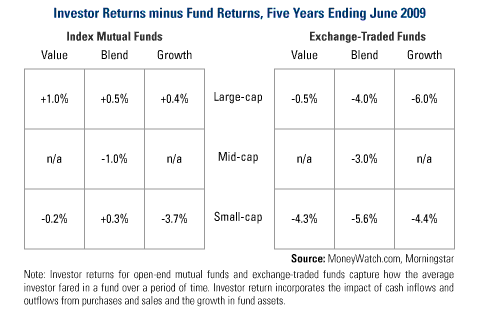

The chart above from MoneyWatch.com shows investor returns minus fund returns for both index mutual funds and ETFs in each available Morningstar “style box” for the five years ending June 2009. Negative figures mean investors lagged the mutual fund or ETF’s return by buying at the wrong time and vice-versa for a positive return.

For example, the average small-cap value ETF investor achieved a return 4.3 percent below what the ETF returned over the same time period. This happens by buying high and selling low. In contrast, the average small-cap value mutual fund investor return was only 0.2 percent below the fund’s performance.

The returns for index mutual fund investors were higher than the returns for the ETF investors for each of the nine style boxes.

And an examination of the five-year returns of more than six dozen ETFs across a range of asset classes by the founder of Vanguard Group concluded that the ETF investors made 18 percent less than the returns of the ETF itself because of the investors’ trading activity.

Unlike mutual funds, ETFs can trade at a premium or discount to their net asset value (NAV). When an ETF investor buys at a premium, he overpays for the asset. Likewise, if he sells at a discount, he receives less than the asset is worth. These premiums and discounts can be wide, especially on days with big NAV changes, and the premiums/discounts can swing very quickly from one extreme to another.

The chart above shows the NAV trading premiums and discounts for the new Market Vectors Junior Gold Miners ETF (GDXJ). Going back to inception, investors have paid premiums to purchase as high as 3.23 percent and sold at discounts as much as 1.28 percent. For the SPDR Gold Shares Trust (GLD), investors paid a 2.15 percent premium to buy in on May 6 (the day of the “flash crash”), but that swung to a 1.3 percent discount just seven trading days later on May 17.

This can work both for and against the investor. Bid-ask premiums or discounts to NAVs can both positively or negatively affect investor return depending on the timing of the transaction. An investor who purchases an ETF at a discount and sells at a premium will receive a higher return than the ETF over the same period of time.

There’s no such thing as a free lunch when it comes to investing. ETFs have relatively low expense ratios compared with actively managed funds in the same sectors, but that doesn’t mean that in the end an ETF costs less to own or that an ETF generates better returns. They can be expensive to trade on volatile days and the events of May 6 uncovered some new weaknesses.

ETFs can have a place in many investment strategies, but before buying, investors need to know what they are getting into so they can make the best decisions consistent with their investment goals.

The full SEC-CFTC Report at SEC.gov and the research from Vanguard is available at IndexUniverse.

Leave a Reply