This post is mostly going to be thinking out loud–I don’t come to a definite conclusion yet. The U.S. faces both a short-term and a long-term fiscal crisis. The short-term problem is the current gap between government spending and government revenues. Arguably that could go away if the economy recovers.The long-term fiscal crisis is the gap between anticipated spending on Medicare and Social Security, and anticipated revenues from payroll taxes.

The question on the table: Could an acceleration of U.S. productivity growth (for whatever reason) enable us to grow our way out of the short-term and long-term fiscal problems? Or, more generally, could an acceleration of U.S. productivity growth boost the U.S. national savings rate, enabling us to save our way out of the fiscal problem?

In the past, I’ve answered this question with an resounding yes. I still think it’s yes, but the answer is more complicated than I thought.

The main reason why it should be possible to grow our way out of debt: An increase in productivity growth–especially one that is not expected–makes the U.S. wealthier and gives Americans higher incomes. One might expect that could increase savings, especially since higher-income, richer households are more likely to save (see, for example, the Fed’s Survey of Consumer Finances). Or to put it a different way, income grows faster than consumption can adjust.

The reasons why it might not be possible to grow our way out of debt:

1) Empirical: During the 1990s and early 2000s, productivity growth accelerated, but consumption accelerated more, so that the savings rate dropped and the trade deficit increased.

2) Empirical: The per-capita cost of health care has grown faster than per-capita GDP in the past (see, for example, the CBOs long-term budget outlook). Assuming that relationship continues in the future, that implies an acceleration of per-capita GDP growth will actually increase the fiscal gap.

3) Legal: Social Security benefits are keyed to average real wages–so if growth accelerates, and wages rise in response, so do Social Security benefits. That means it is very difficult to grow our way out of Social Security issues.

Let’s take these in reverse order.

3) Definitely true. As I’ve written in the past, the Social Security formula probably needs to be adjusted so that benefits don’t quite track real wages.

2) The long-term excess growth of healthcare costs is very interesting. It’s been variously blamed on institutions that make it hard to control costs; the excess cost of new medical technologies; and environmental and social factors (such as increased weight). I personally believe that it represents economic consequences of the innovation shortfall in life sciences that I’ve discussed before–commercially important innovations in areas such as biotech have been few and far between. I would expect that if the pace of successful innovation in the life sciences picks up, that would bring down the rate of growth of health care costs, but there’s no way to test that until it happens.

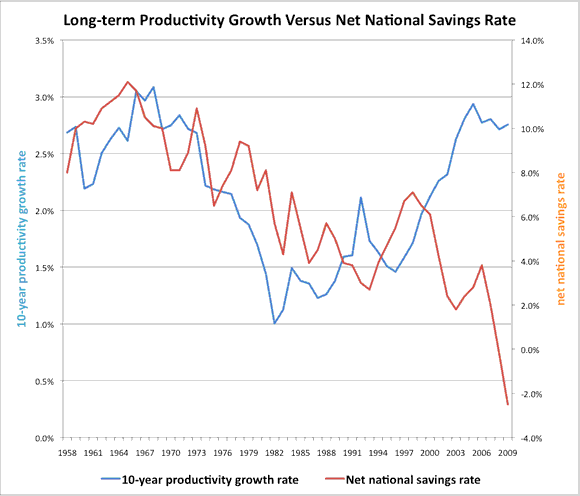

1) This is the hard one, as far as I am concerned. Take a look at this chart:

I’ve chart ten-year nonfarm business productivity growth against the net national savings rate (productivity growth on the left scale in blue, net national savings rate on the right hand scale in brown). What we see is that the two lines roughly parallel each other, as we would expect, up until the late 1990s. Net savings starts to rise as the productivity acceleration begins. Then, poof, productivity growth and net savings go in opposite directions. Despite the unanticipated acceleration of productivity–which boosts output per worker–the savings rate collapses.

Taking this chart at face value is bad news for the “grow our way out of debt” thesis. For one, we had a big acceleration of productivity growth, and the debt problem got worse. To put it another way, we produced more output than expected, and savings went down. Second, it’s hard to imagine that we can get productivity growth up much faster than 3% a year.

But let’s think a bit more about what might explain this surprising divergence. Really, there are four possible explanations:

A) Americans might just be profligate, and quickly ramp up their spending when their income increases (this includes healthcare spending, so it takes in #2 above).

B)The derangement of the financial system and the housing market led people to think that they were richer than they really were (the syndrome of the lottery winner who goes broke).

C) Net savings is mismeasured, and we are really saving more than it seems (spending on education, for example, is counted as consumption).

D) Productivity growth is mismeasured, and the productivity acceleration was really less than it seemed.

If American profligacy is the primary problem, then we are probably out of luck…hard to change. If financial excess is the main problem, then financial reform could be a key factor for helping us grow our way out of debt. If underestimates of savings is the main problem, then we have no problem (because the U.S. is really better off than it seems). If overestimate of productivity growth is the problem, then what happened was that we thought we were richer than we really were, and this led to overspending. (I suspect, for example, that the models for subprime defaults implicitly depended on real wage growth, which is linked to productivity growth).

I personally lean towards D, as I’ve written before. But like I said, I’m not as sure as I once was that we can grow our way out of debt…and that’s just sad.

Leave a Reply