Information technology has dramatically advanced over the years, and it is unreasonable to assume that today it will suddenly cease. But what types of production will be most transformed by future advances, when will the gains will be realized, and in what magnitude? This paper suggests that housing is one sector to be significantly impacted by technical progress, and that some part of the housing boom and bust 2000-2006 was a rational and efficient anticipation of such events.

The prospects for technical progress are exciting, but they are inherently uncertain. We do not yet know how to cure cancer, or how to make a cheap personal computer run at 100 Ghz. Nevertheless, we would be ill-advised to make investment decisions today under the assumption that lifetimes will remain constant, or that personal computers will always run at the same speed. Some of the inputs that are complementary with future technologies – those that are inelastically supplied in the short run – should begin to be accumulated today, even though the progress on which they rely has not yet occurred.

If the new technologies are realized earlier – or in greater magnitude – than originally anticipated, then the complementary inputs will enjoy a favorable and abnormal return. If the new technologies are realized later, or in lesser magnitude, then the complementary inputs will be under-utilized for a while and thereby earn an unfavorable return. This paper modifies the existing economic theory of housing investment to include these ideas. I conclude that at least part of the housing boom occurred because technology was expected to advance in ways that would make existing housing structures more productive.

When a bust occurs as a consequence of bringing the future into better (and less exuberant) focus, the boom time construction was, in hindsight, too much and too soon, but nonetheless the housing stock might not return to its pre-boom trend. As long as there was at least partial truth in the original anticipations – i.e., at least some productivity advance really did occur – then part of the construction boom was necessary and efficient, even with the benefit of hindsight. Housing prices must crash during the bust, but net housing investment may continue to be positive during the bust period. A “bubble” – that is, an increase in housing prices that occurred for no fundamental reason – would not have these properties. Thus, a bust period that keeps the housing stock and housing prices above their pre-boom trends means that housing fundamentals are in fact better, and thereby rejects the pure bubble theory.

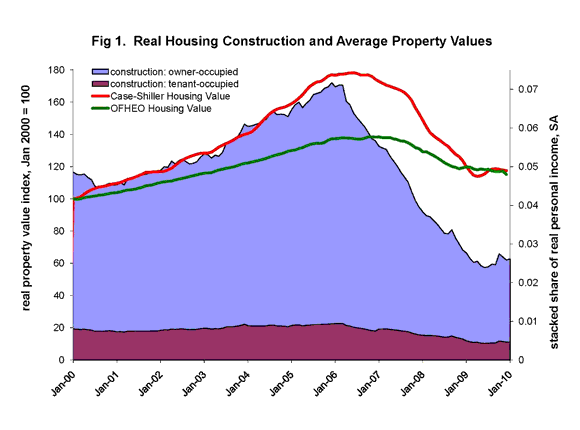

Figure 1 shows the basic price and investment patterns of housing boom and bust to be explained. The left scale shows two monthly measures of the average value of housing properties, known as the “Case-Shiller Home Price Index” and the “OFHEO Home Price Index” divided by the PCE deflator and normalized to 100 in the first month shown (January 2000 [note seasonal adjustment]). The right scale shows residential construction spending, expressed as a percentage of personal income. The bottom series measures tenant-occupied housing construction and the top series adds owner-occupied construction. The Figure shows that real residential construction grew as housing values did through 2005. Sometime between late 2005 and early 2006, both values and construction spending peaked and then declined through early or mid 2009. Since then, construction spending increased a bit, as did one of the measures of real home values (both value measures agree that the 2009 change was significantly less than the changes during 2007 and 2008). The Figure also shows that the large majority of the amount and changes in residential construction spending are for owner-occupied structures.

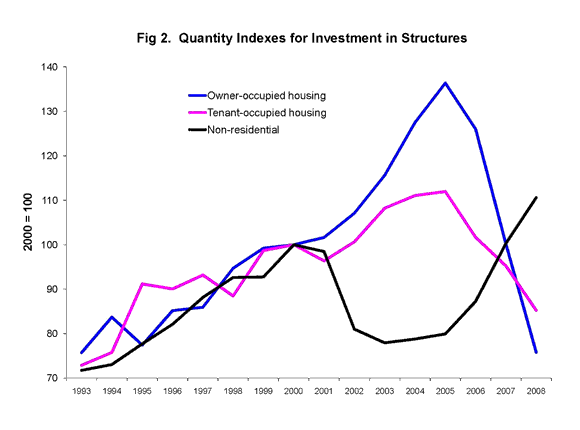

Figure 2 displays quantity indices (2000 = 100) for investment in three types of structures: owner-occupied residential, tenant-occupied residential, and non-residential. The three types of structures investment stayed in about the same proportions 1993-2000. Both types of residential investment increased significantly 2001-2005, and thereafter fell back to pre-boom amounts. In contrast, investment in non-residential structures fell after 2000, and increased significantly 2005-2008. Because the boom increased both types of residential investment and reduced non-residential structures investment, the question addressed in this paper is why housing prices and construction increased 2000-2005, without particular attention to the distinction between owner-occupied and tenant-occupied housing.

The time patterns for housing prices, investment (both residential and non-residential), and income flows qualitatively match my stochastic technology model, and are unlike market responses to a short run shift in housing demand. Thus, the bulk of the housing boom appears to be a response to expectations about the future, and the housing bust a revision of those expectations. Some of those expectations are related to technical change, although it is also possible that additional expectations related to the anticipation of government bailouts, and even irrational exuberance, added to – or even multiplied – the effects of prospects for technical progress.

Section I explains how much of housing output goes for banking services, real estate brokerage, and management, as opposed to the owner of the structure. Structures have a leveraged claim on housing output because they are less elastically supplied than are the housing sector’s other inputs. Moreover, prospects for technical progress in the provision of the elastically supplied inputs should increase both housing prices and housing construction, especially for types of houses that are relatively intensive in the elastically supplied inputs. Section II amends the familiar “q-theory” model of housing investment with an elastically supplied intermediate goods sector. I measure time series for the net operating surplus and vacancy rates emphasized by the theory, and show how they suggest that optimism about the future fueled the housing boom, rather than tastes, technologies, or subsidies during the boom. Section III therefore looks at the market dynamics that would be an efficient response to good news about the future. It shows the expected size of the housing service demand shift – that is, the amount that the housing stock is expected to increase in the long run – that is implied by a given amount of short run housing price elevation. It shows the quantitative expectations about tastes and technology that are required to generate large housing price increases in the short run and housing stock increases in the long run, and how to distinguish the theory from alternative theories of the housing cycle, leaving future research to answer the question of whether such expectations were reasonable. Section IV points out that real housing prices are still higher than they were before the housing boom, despite the boom’s apparent legacy of overbuilding, which suggests that some of the boom’s optimism still remains three years later.

The housing boom that lasted through 2006 featured high and rising real housing prices, high rates of real investment in both owner-occupied and tenant-occupied housing, and low rates of real investment in non-residential structures. Housing sector net operating surplus – that minority part of housing service rents that accrues to homeowners and their creditors – was low relative to the housing stock during the boom, as were occupancy rates. More recently, real housing prices are much lower, although probably still above their pre-boom levels. Housing investment is now below, and non-residential structures investment above, pre-boom levels.

It is sometimes suggested that the housing boom derived largely from low interest rates, and public policies promoting homeownership, in the mid 2000s. But low interest rates by themselves should push up all kinds of structures investment, not just residential structures. And policies to encourage homeownership should have depressed construction of rental housing units, when in fact that construction boomed too. Something else must have changed, and perhaps in a way that interacted with public policies regarding interest rates and home ownership.

That “something else” can be broadly characterized as “optimism” (perhaps rational, perhaps not) about the future because the housing boom featured rising housing prices and low net operating surplus. The facts that the housing boom ended with a large stock of housing yet real housing prices did not fall to pre-boom levels suggests that some of that optimism still remains in the marketplace.

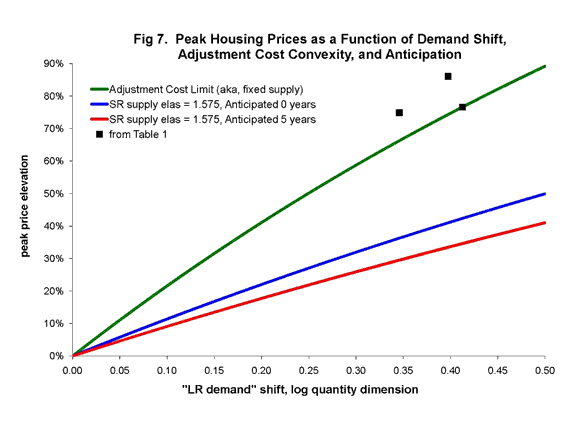

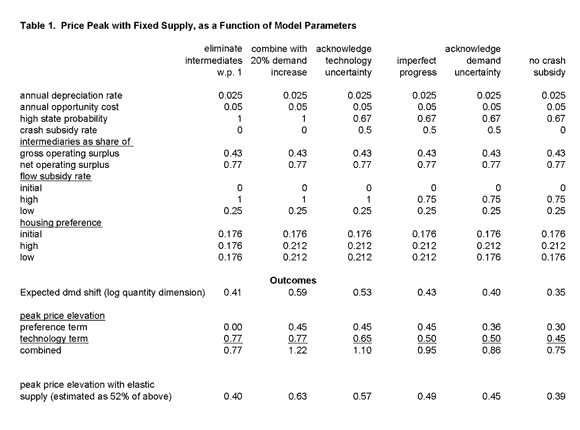

One achievement of this paper is to quantify the expected size of the shift in the long run demand for housing structures that would be consistent with any given peak housing price elevation. For example, Figure 7 reports that real housing prices can be elevated more than 40 percent if the derived demand for housing structures were soon expected to shift by 0.40 log points in the quantity dimension, or 0.46 log points if that shift were anticipated 5 years in advance. To some readers, the stock of housing cannot be reasonably expected to increase that much, even in the long run, so that this result by itself confirms their suspicion that the housing cycle was indeed a “bubble”: a housing boom that was divorced from reasonable expectations about the economic fundamentals.

If the housing cycle is to be linked to fundamentals, then it must be explained why housing structures’ demand would shift so much. Another contribution of this paper is to show how, even in the absence of financial leverage, housing structures are a naturally and significantly leveraged claim on the value of housing services because some of the payments for those services must be used for depreciation, spending on intermediate goods, and property taxes, with only the residual remaining for the owners of structures. Thus, an expected 40 percent increase in real housing service expenditure could elevate housing prices by more than 40 percent in the short run.

Perhaps housing demand was expected to increase as a growing fraction of the population chose to work from home, entertain at home, and otherwise demand more housing. But this paper also points out that reduced production costs in the mortgage and real estate sectors – “housing intermediates” – could ultimately make existing housing more productive. Table 1’s first and second columns show that the derived demand for structures is significantly reduced by the necessity of spending resources on housing intermediates, and thereby that the long run housing stock would be significantly increased if some of those costs could be eliminated. I showed, for example, that a 2/3 probability of a modest housing service demand increase combined with a 75 percent reduction in the costs of housing intermediates would elevate prices by 40 percent or more. An important step for future research is to determine whether such expectations were quantitatively reasonable, and to monitor actual technical progress in the housing intermediates sectors.

The prospects for technical progress are inherently uncertain, so that their effects might be magnified by “irrational exuberance,” subsidies, or both. For example, market participants may focus too much on the rosy technology scenario in which technical progress is realized rather quickly, or in an especially large magnitude. Implicit government guarantees and reasonable prospects for government bailouts may also cause market participants to rationally downweight the less favorable states of nature.

Flood and Hodrick (1990, p. 99) found that “when agents expect the future to be somewhat different than history” price movements induced by fundamentals may look like bubbles to a researcher who is not fully aware of those fundamentals. In this regard, it is difficult to distinguish bubbles from rational expectations, and thus difficult to know whether the housing cycle of the 2000s is something that should have been “fixed.” However, I have strengthened this application of rational expectations theory to assume that agents’ expectations for progress are at least partly correct ex poste – that is, that some progress actually does occur (even if it were smaller or later than originally anticipated) – in which case the two theories are different in terms of the housing stock path after the bust. Perhaps the recession and transitory credit market interruptions are obstacles to immediate execution of this test, but one day we will know whether the housing stock (relative to trend) will ultimately remain above what it was before the housing boom, or instead that the construction boom of the 2000s was completely unnecessary.

Leave a Reply