A wide range of economists have said that employment is low right now because of a lack of demand. As you might guess from the title of this blog, I think supply is more important.

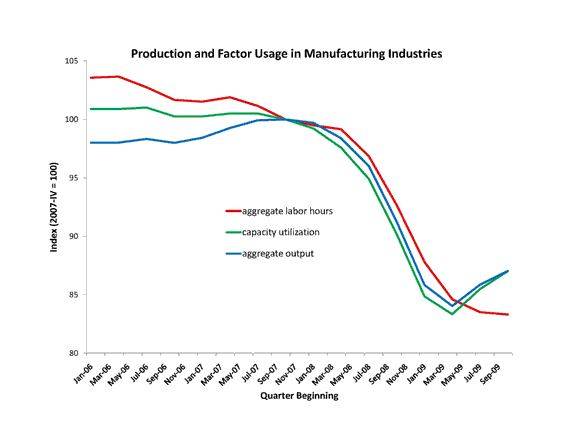

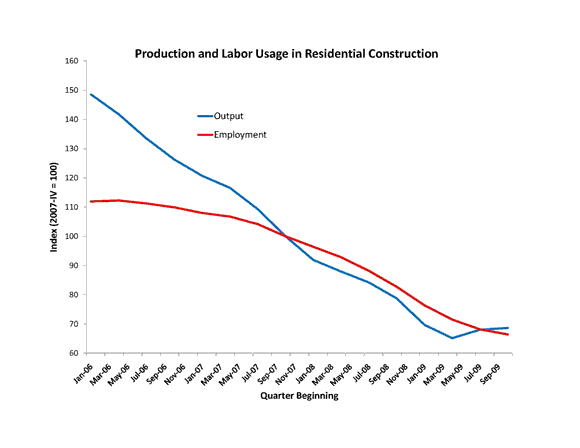

Let’s look at two industries where I agree that lack of demand is dominant: manufacturing and residential building.

In my view, people spend less as a CONSEQUENCE of problems of supply — they recognize that their incomes will be low so that spend less especially on durable goods like cars. While the entire economy suffers from a lack of supply, specific industries like manufacturing are disproportionately affected, so to them the recession is in fact largely a lack of demand.

I also agree with the consensus that, in hindsight, there was too much housing in 2006, so demand for residential building has crashed since then.

A lack of demand will reduce relative prices in the affected industries. A lack of demand will reduce output and factor usage in about the same proportion. In fact, that’s what we see in manufacturing and construction. If anything, labor usage in those industries fell less relative to trend than output did.

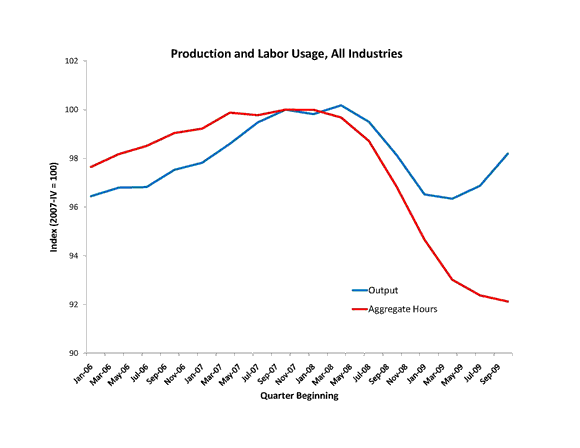

If all industries suffered from a lack of demand, we would see economy-wide labor usage and output falling in about the same proportion.

But you cannot draw the same charts for the economy as a whole, because output and aggregate spending fell much less than labor usage did. Yes, construction, manufacturing, and some other industries suffer from a lack of demand. But problems with the labor market are the primary reason why employment has fallen economy-wide.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply