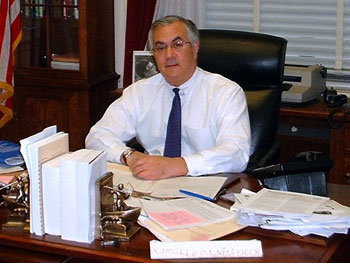

Barney Frank starts off by trying to blame the Bush administrations for the financial crisis:

Barney Frank starts off by trying to blame the Bush administrations for the financial crisis:

And the Clinton Administration was better than the Bush Administration. When the Bush Administration came in, they appointed people who didn’t believe in regulation. So it was not that the banks captured them, it’s that they volunteered to become parts of that operation.

I agree, but it is not at all black and white, as this New York Times story from 2003 shows:

WASHINGTON, Sept. 10— The Bush administration today recommended the most significant regulatory overhaul in the housing finance industry since the savings and loan crisis a decade ago.

Under the plan, disclosed at a Congressional hearing today, a new agency would be created within the Treasury Department to assume supervision of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the government-sponsored companies that are the two largest players in the mortgage lending industry.

The new agency would have the authority, which now rests with Congress, to set one of the two capital-reserve requirements for the companies. It would exercise authority over any new lines of business. And it would determine whether the two are adequately managing the risks of their ballooning portfolios.

The plan is an acknowledgment by the administration that oversight of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac — which together have issued more than $1.5 trillion in outstanding debt — is broken. A report by outside investigators in July concluded that Freddie Mac manipulated its accounting to mislead investors, and critics have said Fannie Mae does not adequately hedge against rising interest rates.

”There is a general recognition that the supervisory system for housing-related government-sponsored enterprises neither has the tools, nor the stature, to deal effectively with the current size, complexity and importance of these enterprises,” Treasury Secretary John W. Snow told the House Financial Services Committee in an appearance with Housing Secretary Mel Martinez, who also backed the plan.

. . .

Significant details must still be worked out before Congress can approve a bill. Among the groups denouncing the proposal today were the National Association of Home Builders and Congressional Democrats who fear that tighter regulation of the companies could sharply reduce their commitment to financing low-income and affordable housing.

”These two entities — Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac — are not facing any kind of financial crisis,” said Representative Barney Frank of Massachusetts, the ranking Democrat on the Financial Services Committee. ”The more people exaggerate these problems, the more pressure there is on these companies, the less we will see in terms of affordable housing.”

Barney Frank defended his actions by arguing that he favored low income rental support, but opposed sub-prime lending. Even so, I can’t help thinking that tighter oversight of the capital reserve ratios would have been helpful. Frank also argues that the Obama administration is doing a much better job regulating:

One of the things that happened under the Bush Administration was the FHA, was allowed to deteriorate. We’re building that back up again with safeguards.

Maybe so, but given that these new ”safeguards” allow people with credit scores of 590 to get FHA mortgages with 3.5% down-payments, I am not reassured. I am also not convinced by the following, although Cochrane and Taylor will agree:

Bernanke and Paulson, came to us in September of 2008 and said, “If you don’t act, there’ll be a total meltdown. There’ll be the worst depression ever.” By the way, even if you didn’t think that was going to be the case, and I think it probably was, when the Secretary of the Treasury and the Federal Reserve say, “If you don’t do this, there’ll be a meltdown,” there’s going to be a meltdown. It’s a little bit self-fulfilling.

If there is one thing we have learned from this crisis, it is that we need to separate politics and banking. There was far too much political pressure (from both Democrats and Republicans) for banks to make loans to people who simply could not afford to pay them back. That wasn’t the only problem, but it was certainly part of the problem. Thus I was not reassured by this statement from Congressman Frank:

They tell us, “Oh, but if you make us pay this tax, we won’t have any money to lend.” First of all, they’re doing a lousy job of lending now and we’ll be having a hearing a couple weeks after this interview to force them to do more if we can.

Have we learned nothing from the crisis?

There are good things in the interview, such as a promise by Frank to end the too big to fail policy. But how can that sort of promise have credibility as long as Congress keeps following the Augustinian maxim:

O Lord, help me to be pure, but not yet.

There is only one comment that really annoyed me:

Unfortunately, the economy was deteriorating, I think as a consequence of their refusal to regulate the financial industry, and President Obama inherited one of the worst recessions in history, the worst since the Great Depression, and it is much harder to do things in a very depressed economy with revenues tied up and people hurting than it was in a good economy. So by the policies that led to this terrible recession that Obama inherited, things became more difficult.

Obama did not inherit the worst recession since the 1930s. Here are some unemployment rates: Nov. 1949 – 7.9%, May 1975 – 9.0%, July 1980 – 7.8%, Dec. 1982 – 10.8%, Jan. 2009 – 7.7%.

Yes, Obama inherited a bad economy. It’s a shame he didn’t ask Cristina Romer how FDR was able to turn things around immediately. How FDR took office in March 1933, a period of rapidly rising unemployment, and within a little over a month had industrial production rising at the fastest rate in history, despite a banking crisis far worse than the one Obama inherited.

By the way, in December 1983 the unemployment rate was 8.3%. Yes, that means that a mere 12 months after unemployment peaked at 10.8% in December 1982, it had already fallen by 2.5%. This time around unemployment peaked at 10.1% in October 2009. I hope it falls by 2.5% by October 2010, but most forecasts I’ve seen suggest it will still be around 10% at that time.

Obama should consider himself lucky that the economy was mismanaged so badly under Bush. This gives him some breathing room, as many people have bought into the false assumption that there is nothing that can be done about the recession in the short run.

By the way, NGDP rose 6.36% in the 4th quarter. This is the best we have seen in quite a while. Nevertheless, I keep emphasizing that the focus needs to be on the expected growth rate of NGDP. We don’t have a futures market, but my reading of various indicators is that NGDP is likely to grow at about 5% going forward, perhaps even less. And that is not enough to recover quickly, although unemployment may fall gradually as wages adjust.

I would also note that nominal final sales only grew by about 3%, and this is the indicator that Bill Woolsey looks at. I think this also explains why most forecasters expect NGDP growth to slow—as the fourth quarter saw a sharp slowdown in the rate of inventory liquidation. But the final sales aren’t there yet to support robust NGDP growth going forward.

I hope this doesn’t sound too negative. The 6.36% figure is much better than what we have recently seen. Further good news comes from the 5.7% rise in RGDP, confirming my supposition that the SRAS is very flat right now, and that any boost to NGDP will mostly show up in the form of higher real output, not higher inflation, until unemployment falls somewhat. Just to be clear, I oppose real targets like unemployment; consider this a prediction of the likely real implications of the nominal target I do favor.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply