I haven’t written much about healthcare reform over the past year, mainly because the public debate has been all about money: How do we pay for extending coverage, how do we reduce the costs, how do we change reimbursements, how do we save the country from going broke, yada yada yada….

But here’s where Obama and company have made their big mistake. They thought that the big problem with the healthcare system was money.

And it’s true, people whine about the cost of healthcare. But in the end, it’s not about the money.The big problem with the healthcare system is that it doesn’t produce enough results for most Americans.

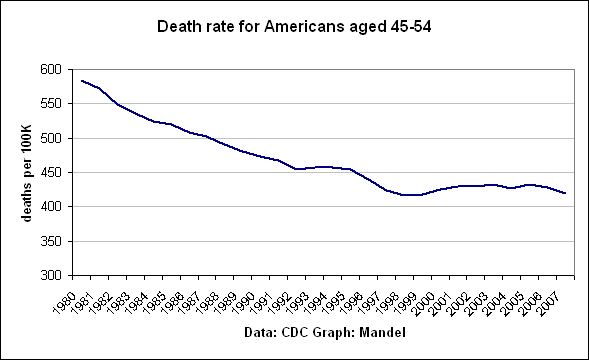

Let’s take a look at a few charts, shall we? Here’s the first one, the death rate per 100,000 for Americans aged 45-54. These are the prime years when people are working, raising kids, and generally at their peak in terms of contributing to society. But they are also the years when we all start feeling the first whiff of mortality–cancer, heart disease, and all sorts of other ills. Speaking for this age group (after all, I’m 52), we want a health care system that addresses these potentially fatal ills.

Uh oh. What do we see? The death rate for us 45-54 year olds hasn’t budged much since the late 1990s. In 2007, the latest year published, the death rate for 45-54 year olds was 419.9, actually up from 418.2 in 1999. That’s a big change from the previous two decades, when the death rate has plunged.

We see no sign in this chart that all of the hundreds of billions of dollars in health care research, and the trillions of dollars in health care spending, are actually paying off. Yes, it’s possible that the health care system is simply struggling to keep up with external factors such as Americans are getting heavier and a possibly deteriorating environment. But now take a look at this chart.

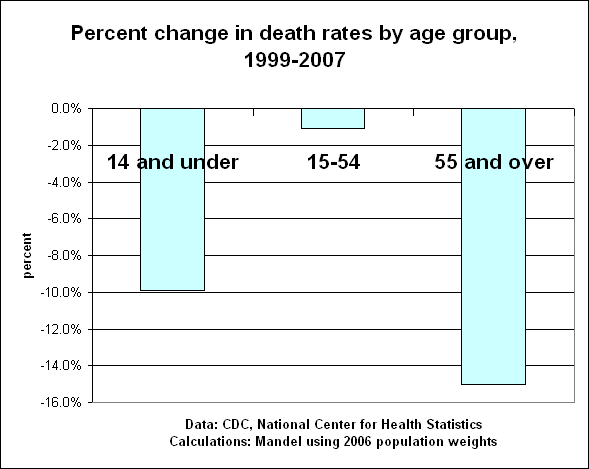

This chart reports the percentage change in the death rate for three broad age groups–14 and under, 15-54, and 55 and over. What we see is that older Americans have seen a very rapid improvement in their odds of dying since the late 1990s. Younger Americans are also less likely to die.

But what about us in the middle? We 15-54ers saw only a 1% decline in our death rates over this period. Not good. Not good at all. Where’s the bang for the buck?

(Technical note: I started with 1999 because I was sure I could get a consistent series over that stretch…the numbers don’t change much with a 1998 start date. I used 2006 population weights to combine groups).

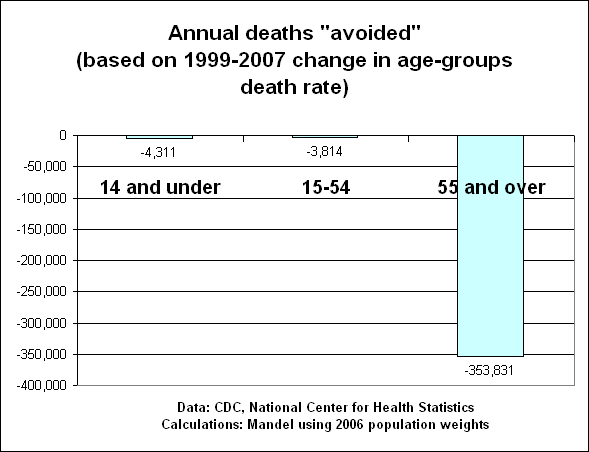

Finally, here’s one more chart. Given the change in the death rate between 1999 and 2007, how many deaths per year were “avoided” in each age group? That is, how many fewer people died in one year because death rates were at 2007 levels rather than 1999 levels?

There’s quite a few ways to do this calculation, but I used the 2006 population as my reference point. Here’s what I got.

In the 14 and under category, the 1999-2007 change in death rates would translate into about 4000 fewer people dying per year. Similarly, in the 15-54 age group, the 1999-2007 change in death rates would translate into about 4000 fewer people dying per year in that age range. The big impact comes from older Americans, with roughly a 350,000 estimated drop in deaths (please treat these as rough estimates..like I said, there are multiple ways to do these calculations).

So let’s summarize. For the people aged 15-54, who make up more than half the population, the health gains have been meager since the late 1990s. Why? I’ll get to that in a future post, but let’s just note for now that many of the health research initiatives which seemed so promising a decade ago have gotten bogged down. For example, cancer death rates have fallen, but the war on cancer has turned into a long-term battle, with some progress but not nearly enough (I’ll get to this more in the next post).

Let’s also note that this stagnation in healthcare outcomes for a big chunk of the population has occurred over the same period that national health care spending roughly doubled (in nominal dollars) . So did the NIH budget. And healthcare employment rose by roughly one-third.

The Obama legislation assumed that healthcare outcomes were fine, and all we had to do was broaden coverage and (perhaps) reduce costs. But if you want to do something that benefits the great majority of Americans who already have health insurance coverage, you have to do something to improve healthcare outcomes.

The first goal of any healthcare reform legislation should be to improve health, for everyone. At the lowest marginal cost, for sure, but it’s never going to be acceptable, politically or morally, to go backwards.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply