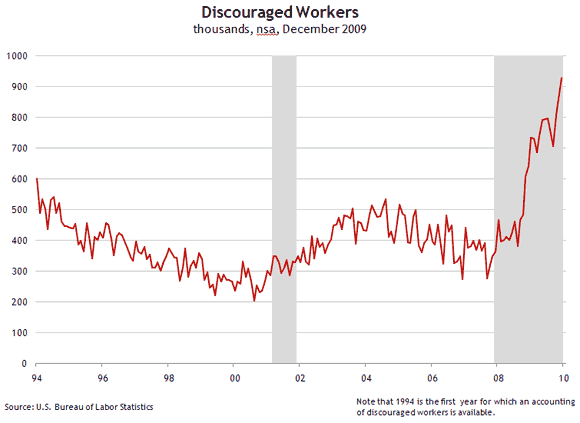

Though they represent only a small fraction of the overall labor force (roughly 0.3 percent on average from 1994 through 2007), discouraged workers have received a good deal of attention lately (here, here, and here, for example) because of the dramatic increase in their numbers during the current recession.

The term “discouraged workers” refers to individuals who are out of the labor force and respond to Bureau of Labor Statistics surveys stating that they are not looking for work because they believe no work is available, could not find work, lack necessary schooling or training, or face discrimination based on age or other factors.

The run-up in the number of discouraged workers is of particular concern to some because of the possibility that all these people (an additional 522,000 since the beginning of the recession) will come flooding back into the labor market, driving the unemployment rate even higher as soon as perceptions of job prospects begin to improve.

Say these discouraged workers were to start re-entering the labor force in 2010. How many jobs would need to be created each month to absorb them? While there is a danger in taking stocks and trying to translate them into flows, this exercise does provide some framework with which to talk about the impact discouraged workers re-entering the workforce might have on the unemployment rate going forward.

In order to make that calculation, we need to make some assumptions about how quickly the discouraged workers might re-enter the labor market. Using the previous recession and recovery as a guide, discouraged workers might return to the labor market at a slightly slower rate than when they exited it. From the fourth quarter of 2001 through the first quarter of 2005 (the previous peak in the number of discouraged workers), the number of discouraged workers increased at an average quarterly rate of 3.4 percent. From the first quarter of 2005 through fourth quarter of 2007, the number of discouraged workers decreased at an average quarterly rate of about 2.7 percent.

Applying this same ratio (3.4 percent/2.7 percent) to the 19 percent average quarterly run-up between the fourth quarter of 2007 through the fourth quarter of 2009, we could see an average quarterly decline in discouraged workers of about 15 percent. This number suggests that, if we are at a new peak of discouraged workers, we could see 414,000 discouraged workers re-entering the work force in 2010, which would represent an average of around 34,500 workers per month. This number represents 0.02 percent of the U.S. labor force in December 2009. If these discouraged workers were the only workers joining the labor force, the economy would need to create roughly 30,000 jobs each month to keep the unemployment rate the same (10 percent).1

How quickly the discouraged workers will re-enter the labor force, holding everything else constant, is not necessarily the most important question. A more significant question is how quickly the overall labor force will grow. Employment would need to grow at the same rate as the labor force in order for the unemployment rate to remain at 10 percent, which amounts to roughly 91,000 jobs per month if we use the average annual growth rate of the labor force during the three years following the 2001 recession, which was 0.84 percent.

Bottom line: While not insignificant, the number of discouraged workers that can be expected to re-enter the labor market once job prospects turn around is only a small piece of the puzzle. More focus should instead be placed on the larger issue of job creation.

Footnote: 30,000 represents 0.02 percent growth in jobs that will be needed to absorb the 0.02 percent growth in the labor force that is reflected in the 34,500 number: (131 million)*(0.0002)=26,200, or, roughly 30,000.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply