I love to take a contrarian position. The more contrarian the better. But only if I truly think I am right. This post will be a lot of fun because these days you can’t get much more contrarian than defending Eugene Fama on the EMH. But I also happen to think Fama is right. Really, I do. Indeed I think I can show that he is right, or at least much more likely to be right than most people imagine.

This was triggered by the barrage of criticism he has been receiving. If you read posts like this one from Free Exchange, you’d think this giant of financial economics, this future Nobel laureate, is a complete fool. Maybe he is, but if so then I am too. Here’s the New Yorker’s Cassidy, then Fama, then Free Exchange:

(Cassidy) Are you saying that bubbles can’t exist?

(Fama) They have to be predictable phenomena. I don’t think any of this was particularly predictable.

(Free Exchange) This is truly remarkable. A bubble is an unsustainable increase in prices relative to underlying fundamentals. These fundamentals are more or less observable; those who called the housing bubble did so based on historically anomalous increases in the ratio of home prices to rents and incomes. And many people did correctly identify the bubble years before it imploded, including writers at The Economist who were worrying about rapid home price increases while the American economy was still limping out of the 2001 recession. This is the reality that Mr Fama seems unwilling to confront. How unwilling?

So that is the pro-bubble argument. We can know the fundamental prices of assets. We can know when asset prices move away from their fundamental value. And when they do we can predict that at some point over a reasonable period of time (say a few years) they are likely to move back toward their fundamental values. I hope that is what Free Exchange is claiming; if not I have no idea what the argument is. But if that is the claim, it is wrong on all three counts. I’ll come back to housing eventually, because his assertions are incorrect, but first I’d like to look at the Fidelity Latin America fund, as this perfectly illustrates my point.

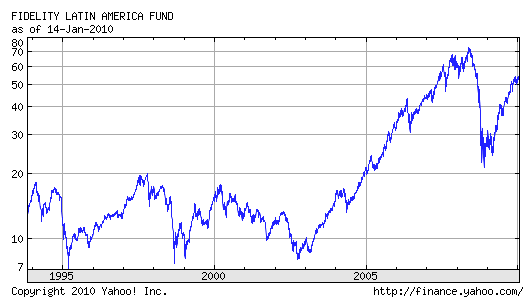

You are probably thinking “why the Fidelity Latin America Fund?” Well first of all, if you are one of those people who believes in bubbles, and you haven’t been paying attention to the FLAF, you sure are missing the boat. It certainly looks like a bubble. But this is also what efficient markets look like. They are erratic. They have peaks and valleys. It looks like they have bubbles, but that is a cognitive illusion. No one really knows the fundamental value of Latin American stocks. As a result the price can move around quite a bit, even when the so-called “fundamentals” haven’t changed very much.

Anyone who believes in bubbles should have been able to make a lot of money either shorting or going long on the FLAF. (Maybe these stocks can’t be shorted, but my point will still hold up as there are plenty of stocks that can be shorted. So please don’t bring up that objection.) So let’s say The Economist magazine really knows the fundamental value of assets in the various countries it covers. It does cover a lot of countries, and probably knows more about those countries than almost any other magazine. Also suppose The Economist started a mutual fund that invested based on its ability to spot fundamental values and deviations from those values. That mutual fund should outperform other funds. And not just by a little bit, but massively outperform them. Just look at the graph. Did the fundamentals in Latin America (a slow growth area where RGDP grows about 4%) really increase 10-fold between the summer of 2002 and early 2008? I am almost certain they’d say no. So there are great profit opportunities. And not just here, The Economist covers the whole world, and all sorts of assets. They make predictions about real estate, about commodities, about all sorts of things. There are always some markets that are “underpriced” and others that are “overpriced.”

At this point I’m sure that people are saying “that’s not fair, they aren’t claiming to be able to beat the market.” But unless I am mistaken, that is exactly Fama’s point. Unless your Nostradamus-like ability to spot fundamental values does give useful predictions of where asset prices are going, with at least more than a 50/50 chance of success, then the theory of bubbles you have developed is essentially worthless. It would have no utility, for investors and more importantly for regulators.

Now let’s ask why people have this mistaken notion that bubbles are easy to spot, and that Fama is deluded. I believe it is a cognitive illusion. People think they see lots of bubbles. Future price changes seem to confirm their views. This reinforces their perception that they were right all along. Sometimes they were right, as when The Economist predicted the NASDAQ bubble, or the US housing bubble. But far more often people are wrong, but think they were right. The most famous example is Shiller’s famous “irrational exuberance” call of early 1996. Most people still think Shiller was right. But he was wrong, or at least it is far from clear whether the prediction was at all useful. (Over the last 14 years there are many times when he looked wrong, and many times he looked right.)

Now suppose you were a bubble proponent and you starting watching the FLAF when it was down around 7 in late 2002. You watch it double to 14, and say to yourself, hmm, a bit pricey, looks like a bubble might be forming. Then it goes to 21, nearly tripling in value. Now you are really starting to think bubble. It’s mostly in Brazil. But Brazil isn’t China, it grows at about 3%. The joke is “Brazil’s the country of the future, and always will be.” Now it goes to 28, up almost 4 times higher than the 2002 lows. Surely no plausible amount of profit growth can justify that rise. Now the bubble alarms are going full blast. Sell, sell, sell. Except anyone who took your advice would have been a fool. It went to 35, then 42, then 49, then 56, then 63, then over 70.

Now suppose I wrote this post in the spring of 2008. A few months later I’d look like a complete idiot. The FLAF crashed. The bubble theorists would have had their worst fears realized. They’d say “I told you so” even though they would have been wrong, even though the post crash price was still near 28. And now it’s back to 52. What is the fundamental value? For a Rortian pragmatist like me that question is absurdity piled on absurdity. Or what Bentham called “nonsense on stilts.” There is no “fundamental value.” There are only amounts people think it is worth. Individual people, and the market consensus. There are no outside referees like “God” to tell us who is right. We are all alone. All I can say is that the price will continue to fluctuate. I have no idea which way. And at times the bears will make money, and at other times the bulls will come out ahead.

But there is one thing I can predict with a high degree of confidence. Whatever happens to the FLAF over the next 50 years, the price movements will be interpreted through this congnitive illusion, this confidence that we can see patterns in graphs, even where they don’t exist. The “mountain peaks” will look like bubbles. In fact, you can generate a “stock graph” by just flipping coins repeatedly. And if you show the resulting graph to the average investor he will see patterns. It is all a cognitive illusion.

But why is Fama’s theory now in such disrepute? Because in the past ten years the world economy has seen two very important bubble-like patterns, indeed arguably the only two such market cycles in the US during my lifetime with macro significance. And they were both predicted by lots of experts because they violated popular theories of fundamentals. So start with the cognitive illusion that people have that makes them see bubbles even where there don’t exist. People think they have made accurate predictions because an upswing is always EVENTUALLY followed by a downturn. Then add in the fact that The Economist really did make accurate predictions in two of the most important events in modern history. Do you think it will be possible to convince them that they just got lucky? About as likely as a husband convincing an already suspicious wife that he is innocent after twice being caught in bed with two separate women. So I feel sorry for Fama. He’s probably right, but I don’t see how he could ever convince anyone in this environment. It would be like trying to convince someone that neoliberalism was the right policy in 1933. (Come to think of it, The Economist advocates neoliberalism.)

Now let’s return to housing, and the false claims made by Free Exchange. In fact, it is not easy to predict the fundamental value of housing. In a previous post I pointed out that many people screamed bubble when the tight American coastal markets began to diverge from “flatland” prices. This occurred during my lifetime, and I know that it caught a lot of people off guard. When I moved from the Midwest to Boston in 1982 house prices didn’t seem that high to me. By 1987 they had doubled. By 1990 they’d fallen 15% and I recall people in Boston saying; “see, I knew all along that house prices were completely out of whack in 1987.” Except that there is just one problem, the prices starting rising again. By a lot. More recently they have fallen again in the coastal markets. But it clear to me that in the tight coastal housing markets prices diverged from fundamentals (or Midwestern prices), and never really returned. Free Exchange suggests you can get the “fundamental” values by looking at ratio of house prices to income. Will that work in NYC? How about San Francisco? Actually, if I wanted to play that game I’d estimate the fundamental value as the cost of construction plus land prices. And land prices really don’t have any fundamental value.

Just to be clear, I’m not trying to model housing prices, I’d be the first to admit that the sharp run-ups in Vegas and Phoenix look irrational. My point is that housing prices are usually hard to predict, because land prices are hard to predict. Houses can become “unaffordable” in places like NYC and SF, and stay unaffordable for decades. Of course they aren’t really unaffordable, as people are living in them. But they appear unaffordable according to the sort of metrics used by the bubble proponents. These bubble criers were wrong in 1990 when they thought they were right. Housing prices in desirable coastal markets could well stay much higher than flatland markets for many decades to come. Or they might not.

A lot of bubble proponents say that the bubble theory doesn’t allow investors to make abnormal returns. I don’t buy that and I don’t think Fama does either. I think you can sense Fama’s exasperation in his answers. Reporters like anecdotes, they think in terms of specifics. Academics like models, generalities, principles. Fama wants to know what exactly the bubble proponents are saying. I don’t want to put words in his mouth, but I think that he is sort of saying the following.

1. Either you are claiming that a mutual fund run on The Economist’s predictions would reliably outperform index funds.

2. Or you are saying something with no meaningful implications that I can understand, and you have drained the term ‘bubble’ of any useful meaning.

I think Fama would regard the first claim as delusional and absurd, and I’d agree. So then what is the point of bubble theories, what are they suppose to tell us that is useful? Here’s another Fama quote from Free Exchange, see if I have interpreted him correctly:

That’s what I would think it is [i.e. a bubble], but that means that somebody must have made a lot of money betting on that, if you could identify it. It’s easy to say prices went down, it must have been a bubble, after the fact. I think most bubbles are twenty-twenty hindsight. Now after the fact you always find people who said before the fact that prices are too high. People are always saying that prices are too high. When they turn out to be right, we anoint them. When they turn out to be wrong, we ignore them. They are typically right and wrong about half the time.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply