This guest post was contributed by Charles S. Gardner, a former senior official at the International Monetary Fund. He argues we must not overlook the importance of extending effective regulation to the nonbank sector.

This guest post was contributed by Charles S. Gardner, a former senior official at the International Monetary Fund. He argues we must not overlook the importance of extending effective regulation to the nonbank sector.

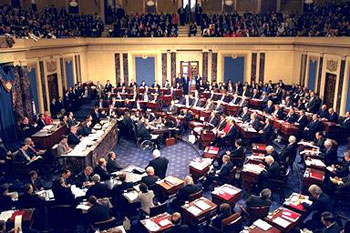

As Congressional action on financial industry reform shifts to the Senate from the bill passed recently by the House, the urgent need now is to fill the gaps in the piecemeal House approach. Regulators require an airtight scheme giving them clear responsibility plus tools to nip industry abuses early and drain the tendency to crisis out of world finance. This rare opportunity also must be seized to restore the Federal Reserve’s control of the money supply, eroded by decades of expanding credit creation by nonbanks.

So far, Congress has ignored this macro dimension of the reform challenge. Understandably, the House Financial Services Committee focused mainly on the high-profile villains of the financial crisis enraging constituents from coast to coast: obscene pay practices, secret but deadly derivatives trading, the murky role of hedge funds, boundless leveraging of assets, and heedless loan packaging that left the originators both rich and risk free.

The House bill deals separately with the welter of technical issues in each of these problem areas. It falls to the Senate now to take a step back and make sure that the pieces add up to more, not less, than the sum of their parts. Each piece may give regulators new and essential information for monitoring and controlling an industry practice, but will the new information fuse into the comprehensive picture needed for intelligent, forward-looking regulation?

For example, requiring open trading of derivatives will help regulators identify potentially risky credit creation outside the regulated banking industry. But will that be enough to assure preemptive action? The Fed or another agency should have explicit authority to oversee and regulate any nonbank entity engaging in leveraging assets and creating credit. Since at least the 1960s, unregulated nonbank activity has been an increasing source of credit creation, ultimately equaling or surpassing the volume under regulation.

If nonbanks like AIG, GMAC and GE—and long before that LTCM—can threaten the stability of world capital markets, the time has come to regulate them in advance de jure not wait for a crisis that brings them under regulation de facto because they need a bailout.

Last fall’s financial catastrophe made the prudential case for direct regulation of nonbanks. The macroeconomic case built less noticeably for decades, steadily eroding Federal Reserve power to manage the monetary system. A turning point came during the chairmanship of Paul Volcker when traditional monetary aggregates became so meaningless they were no longer a useful focus of Fed policy and it switched to targeting inflation directly. In place of a solid advance indicator of price movements to guide policy, the Fed had to fall back on its skills at prediction to manage credit and the price level.

As the Fed now confronts the tough timing challenge of heading off inflation without killing the recovery, wouldn’t it be in a stronger position with a comprehensive picture of the money supply? Or could it have ignored the rapid buildup leading to the mortgage market bubble had its data been more complete?

The steady weakening of the Fed’s real power to deliver noninflationary growth was accompanied by a greater reliance on the personality of its chairman to sustain its credibility. As long as the economy was performing reasonably well and periodic crises were not too severe, the chairman could promote the illusion of a Federal Reserve in reasonable control. The illusion shattered in 2004 when the Fed belatedly tried to raise interest rates only to see longer rates fall instead. Puzzlement prevailed at the time but the conundrum was really evidence of how weakened Fed leverage had become.

Since the financial meltdown, a disillusioned public is now blaming the Fed for a failure to exert power it did not really have: the nonbanking sector operated outside the reach of both its prudential and monetary policy regulation. The sad result is a backlash in Congress threatening to reduce the Fed’s power when it should be restored and enhanced. It may be quixotic now to suggest that useful monetary aggregates could be reconstructed; but if they could, it would help rebuild the Fed’s stature on the basis of technical competence, and reduce its reliance on a cult of personality. In the end, Congress may hand the tasks of consumer protection and bank oversight (and hopefully nonbank oversight as well) to other agencies, leaving the Fed with its core monetary policy responsibility. Even with this outcome, Congress should temper its anger at the Fed with wisdom to equip it for its responsibilities.

The debate over curbing companies seen as “too big to fail” is likely to be pivotal in whether the Senate will strive for an effectively airtight regulatory regime. To date, this debate has played more to public anger at banks than to regulatory substance. Sheer size, after all, has been less a cause of the crisis than industry practices that are too complex, too opaque, and too unregulated. If sheer size is a factor in anticompetitive behavior, antitrust criteria should be used to deal with it, not some arbitrary concept of “too big.”

Until recently, the “too big to fail” argument was justified. It is an argument the public can understand. Its bumper sticker appeal was useful when it looked as if Congress was foot dragging, and the risk was real that public anger could dull and undermine the drive for reform. Clearly, public anger is not going away. Congress is moving quickly to send a huge reform package for the President’s signature early next year.

Now, however, the risk is that the “too big to fail” argument will be an impediment to enacting comprehensive regulation. In its simplicity, it is, after all, an admission that fully effective financial industry reform may be unachievable. Can’t the rich financial firms always hire smarter, quicker lawyers, capable of defeating the best technical drafting and oversight that underpaid government bureaucrats can field? This defeatism quickly leads to the idea that any legislative result is good enough if it produces sufficient punishment now for the arrogant financial industry, even if it will be evaded in the longer term.

Neither the U. S. public nor the financial industry will benefit from this flawed result. The largest damage, however, is likely to be to international efforts to make the globalized financial system safer and more efficient at capital distribution. Here, the United States has a special responsibility to get domestic regulation right because it will be in the forefront in fighting international controls and insisting on regulation confined to the national level. A high level of transparency will be needed in each major national system for this approach to work, and it will be up to the United State to provide the model.

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply