As the US debt-to-GDP ratio rises towards 100%, policymakers will be tempted to inflate away the debt. This column examines that option and suggests that it is not far-fetched. US inflation of 6% for four years would reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio by 20%, a scenario similar to what happened following WWII.

Since the start of 2007, the financial crisis has triggered $1.62 trillion of write-downs and credit losses at US financial institutions, sending the American economy into its deepest recession since the Great Depression and the global economy into its first recession since World War II. The US Federal Reserve has responded aggressively. Fiscal policy has become expansionary as well. The US is now facing large deficits and growing public debt. If economic recovery is slow to take hold, large deficits and growing debt are likely to persist for a number of years. Not surprisingly, concerns about government deficits and public debt now dominate the policy debate (Cavallo and Cottani 2009).

Many observers worry that the debt-to-GDP ratios projected over the next ten years are unsustainable. Assuming deficits can be reined in, how might the debt/GDP ratio be reduced? There are four basic mechanisms:

1. GDP can grow rapidly enough to reduce the ratio. This scenario requires a robust economic recovery from the financial crisis.

2. Inflation can rise, eroding the real value of the debt held by creditors and the effective debt ratio. With foreign creditors holding a significant share of the dollar-denominated US federal debt, they will share the burden of any higher US inflation along with domestic creditors.

3. The government can use tax revenue to redeem some of the debt.

4. The government can default on some of its debt obligations.

Over its history, the US has relied on each of these mechanisms to reduce its debt/GDP ratio. In a recent paper (Aizenman and Marion 2009), we examine the role of inflation in reducing the Federal government’s debt burden. We conclude that an inflation of 6% over four years could reduce the debt/GDP ratio by a significant 20%.

The facts

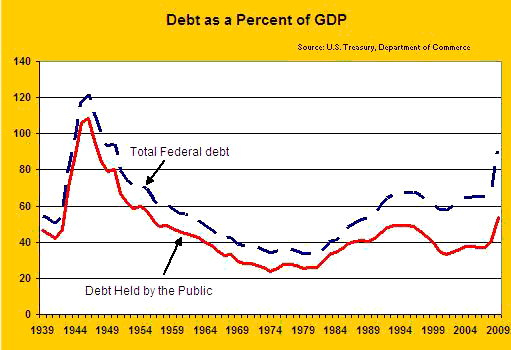

Figure 1 depicts trends in gross federal debt and federal debt held by the public, including the Federal Reserve, from 1939 to the present. In 1946, gross federal debt held by the public was 108.6%. Over the next 30 years, debt as a percentage of GDP decreased almost every year, due primarily to an expanding economy as well as inflation. By 1975, gross federal debt held by the public had fallen to 25.3%.

Figure 1. Debt as a share of GDP

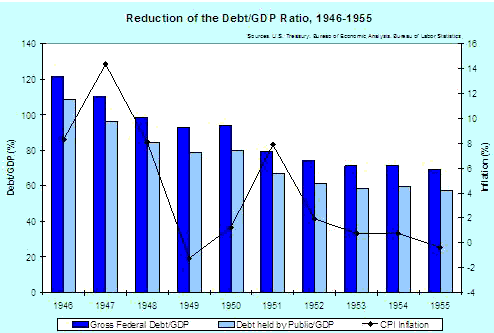

The immediate post-World War II period is especially revealing. Figure 2 shows that between 1946 and 1955, the debt/GDP ratio was cut almost in half. The average maturity of the debt in 1946 was 9 years, and the average inflation rate over this period was 4.2%. Hence, inflation reduced the 1946 debt/GDP ratio by almost 40% within a decade.

Figure 2. US debt reduction, 1946-1955

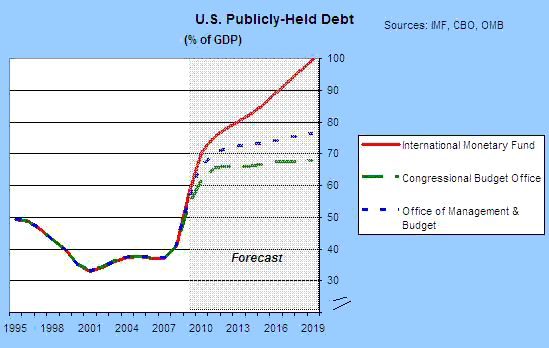

In recent years, the debt/GDP ratio has increased dramatically, exacerbated by the financial crisis. In 2009, it reached a level not seen since 1955. Figure 3 shows three 10-year projections, indicating debt held by the public could be 70-100% of GDP in ten years.

Figure 3. America’s projected debt burden

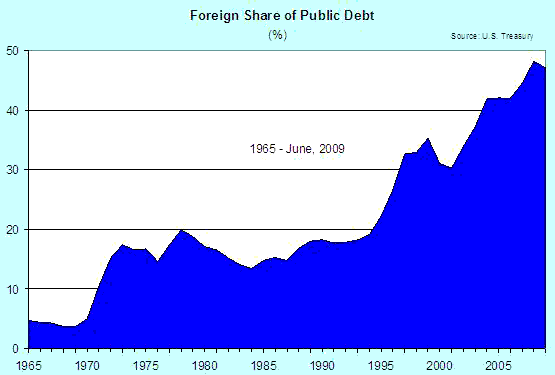

A government that has lots of nominal debt denominated in its own currency has an incentive to try to inflate it away to decrease the debt burden. If foreign creditors hold a significant share of the debt, the temptation to use inflation is greater, since they will bear some of the inflation tax. Shorter average debt maturities and inflation-indexed debt limit the government’s ability to reduce its debt burden through inflation.

Figure 4 shows the share of US public debt held by foreign creditors. The foreign share was essentially zero up until the early 1960s. It has risen dramatically in recent years, particularly since the 1997-98 Asian financial crisis, and was 48.2% of publicly held debt in 2008. Thus foreign creditors would bear about half of any inflation tax should inflation be used to reduce the debt burden, with China and Japan hit hardest.

Figure 4. Foreign share of publicly held debt

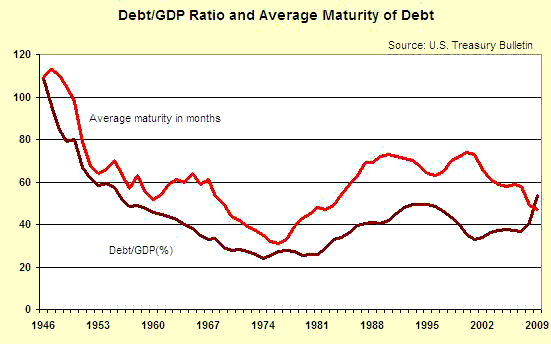

Figure 5 illustrates the average maturity length for US marketable interest-bearing public debt held by private investors, along with the debt held by the public as a share of GDP. As noted by a number of authors, the US exhibits a positive relation between maturities and debt/GDP ratios in the post-World War II period. Most developed countries show little correlation between maturities and debt/GDP ratios. The US appears to be an exception. Maturity length on US public debt in the post-World War II era went from a 9.4 years in 1947 to a low of 2.6 years in 1976. In June, 2009, the average maturity was 3.9 years. Most of this debt is nominal.¹

Figure 5. Average maturity length and share of debt held by the public

Inflating away some of the debt burden

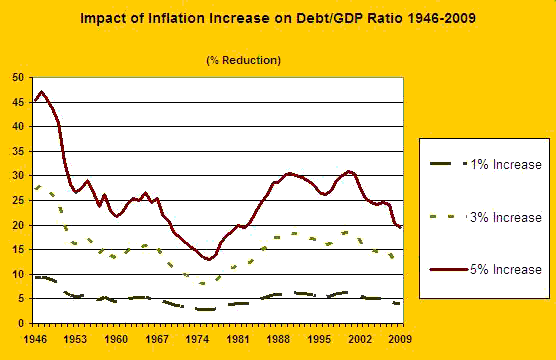

Figure 6 illustrates the percentage decline in the debt/GDP ratio under various inflation scenarios.² Inflation yielded the most dramatic reduction in the debt/GDP ratio – and the real value of the debt – in the immediate post-World War II period. A 5% inflation increase starting in 1946, for example, would have reduced the debt/GDP ratio from 108.6% to 59.3%, a decline in the debt ratio of 45%. Not only was there a large debt overhang when the war ended, but inflation was low (2.3%) and debt maturity was high. Thus there was room to let inflation rise – and it rose to 14.4% in 1947 before dropping considerably. Average inflation over the decade was 4.2%. Moreover, long maturities allowed inflation to erode the debt burden. Maturities were over 9 years in years 1945-48 and then fell gradually to 8.17 years in 1950.

Figure 6. Impact of inflation on publicly-held debt as a share of GDP

In contrast, inflation would have had little impact on reducing the debt burden in the mid-1970s. That period was characterised by a lower debt overhang, inflation was higher, and debt maturities were shorter (under 3 years). As a result, in 1975 a five-point increase in inflation would have reduced the debt/GDP ratio from 25.3% to 21.9%. The estimated impact of inflation on today’s debt/GDP ratio is larger than in the mid-1970s but not as large as in the mid-1940s. If inflation were 5% higher, the debt/GDP ratio would be about 20% lower, a debt ratio of 43.4% instead of 53.8%. Our computations of the impact of inflation on the debt overhang assume that all debt is denominated in domestic currency, none is indexed, and the maturity is invariant to inflation. Regression analysis confirms that US debt maturities over the period 1946-2008 are not responsive to inflation.

We develop a stylistic model that illustrates both the costs and benefits associated with inflating away some of the debt burden. The model, inspired by Barro (1979), shows that the foreign share of the nominal debt is an important determinant of the optimal inflation rate. So is the size of the debt/GDP ratio, the share of debt indexed to inflation, and the cost of collecting taxes. A lesson to take from the model and the simulations is that eroding the debt through inflation is not farfetched. The model predicts that inflation of 6% could reduce the debt/GDP ratio by 20% within four years. That inflation rate is only slightly higher than the average observed after World War II. Of course, inflation projections would be much higher than 6% if the share of publicly-held debt in the US were to approach the 100% range observed at the end of World War II.

Interpretation

The current period shares two features with the immediate post-World War II period. It starts with a large debt overhang and low inflation. Both factors increase the temptation to erode the debt burden through inflation. Even so, there are two important differences between the periods. Today, a much greater share of the public debt is held by foreign creditors – 48% instead of zero. This large foreign share increases the temptation to inflate away some of the debt. Another important difference is that today’s debt maturity is less than half what it was in 1946 –3.9 years instead of 9. Shorter maturities reduce the temptation to inflate. These two competing factors appear to offset each other, and the net result in a simple optimising model is a projected inflation rate slightly higher than that experienced after World War II, but for a shorter duration.

In the simulations, we raise a concern about the stability of some model parameters across periods, particularly the parameters that capture the cost of inflation. It may be that the cost of inflation is higher today because globalisation and the greater ease of foreign direct investment provide new options for producers to move activities away from countries with greater uncertainty. Inflation above some threshold could generate this uncertainty, reducing further the attractiveness of using inflation to erode the debt.

Moreover, history suggests that modest inflation may increase the risk of an unintended inflation acceleration to double-digit levels, as happened in 1947 and in 1979-1981. Such an outcome often results in an abrupt and costly adjustment down the road. Accelerating inflation had limited global implications at a time when the public debt was held domestically and the US was the undisputed global economic leader. In contrast, unintended acceleration of inflation to double-digit levels in the future may have unintended adverse effects, including growing tensions with global creditors and less reliance on the dollar.³

Footnotes

¹ Treasury inflation-protected securities, or TIPS, account for less than 10% of total debt issues.

² The calculation assumes that maturity is invariant to inflation. We test and overall confirm the validity of this assumption for U.S. data in the post-World War II period.

³ For the threat to the dollar from the euro, see Chinn and Frankel (2008) and Frankel (2008).

References

•Aizenman, Joshua and Nancy Marion (2009), ‘Using Inflation to Erode the US Public Debt,” NBER Working Paper 15562.

•Barro, Robert (1979), “On the Determination of the Public Debt”, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 87, 940–71.

•Cavallo, Domingo and Joaquín Cottani (2009), “A simpler way to solve the “dollar problem” and avoid a new inflationary cycle”, VoxEU.org, 12 May.

•Chinn, Menzie and Jeffrey Frankel (2008), “Why the Euro Will Rival the Dollar”, International Finance, 11(1), 49-73.

•Frankel, Jeffrey (2008), “The euro could surpass the dollar within ten years”, VoxEU.org, 18 March.

![]()

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply