Here are some assorted monetary musings:

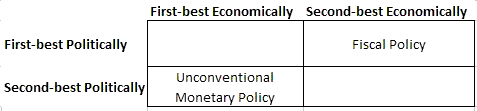

(1) Paul Krugman comes clean and acknowledges unconventional monetary policy can still pack a punch. In fact, he says the “first-best answer” to our current economic crisis is not expansionary fiscal policy, but a credible commitment by the Federal Reserve to higher inflation. An exasperated Scott Sumner who has been making this case for some time wonders why Krugman has taken so long to acknowledge this point. Krugman replies that he has not pushed this idea because he believes it will not get any traction. As a result he turned to expansionary fiscal policy as a second-best solution. In other words, Krugman believes he faces the following tradeoff regarding aggregate demand-stabilizing policies:

Krugman may be right on this policy tradeoff. But given Krugman’s immense political influence, he could have made this issue front and central for policymakers. And with enough exposure unconventional moneary policy could have become a first-best political solution too. In short, had Krugman been pushing this idea some time ago it may have gone a long way in preventing the collapse in nominal spending over the past year. Moving forward, it is good to remember that it was unconventional monetary policy (and not fiscal policy) that ended the Great Contraction of 1929-1933. So too can it now keep the U.S. economy from entering a prolonged slump.

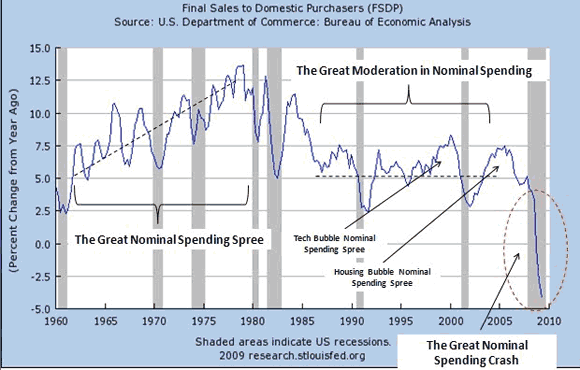

2. Speaking of Scott Sumner, I did a long run yesterday and listened to his podcast with Russ Roberts to pass the time. It was good interview and covered many of the same issues Scott has made on his blog. One of the points he made is that monetary policy could improve its ability to stabilize the macroeconomy by targeting some measure of nominal spending. I too am an advocate of the Federal Reserve stabilizing nominal spending for the same reasons. However, I am a little less confident that it is always a sufficient policy response in terms of stabilizing the macroeconomy. For example, if we look at the period called the “Great Moderation” that occurred during the 25+ years prior to the current crisis, we see the Federal Reserve did a fairly good job on average of stabilizing nominal spending around 5% growth (See the figure below).

However, this time was also a period of the Fed asymmetrically responding to swings in asset prices. Asset prices were allowed to soar to dizzying heights and always cushioned on the way down with an easing of monetary policy. This behavior by the Fed appears in retrospect to have caused observers to underestimate aggregate risk and become complacent. It also probably contributed to the increased appetite for the debt during this time. These developments all contributed to current crisis. To the extent, then, that stabilizing nominal spending requires the Fed to respond as it did to swings in asset prices during this time, then it becomes less clear to me that targeting nominal spending is always a sufficient condition for macroeconomic stability. Don’t get me wrong, I still believe a nominal spending target would have done much to prevent the collapse in nominal spending over the past year and ultimately it would be an improvement over current Fed policy. The gradual buildup of excesses during the “Great Moderation”, though, suggest to me that something more is needed. That is why I see a two part approach to macroeconomic stability: (1) target nominal spending and (2) implement macroprudential regulations.

2. It was a really long run so I also listened to a podcast where Bloomberg’s Tom Keene interviewed Bruce Bartlett about his new book The New American Economy. It was an interesting interview, but at one point Bartlett claimed there was nothing more monetary policy could for the economy at this point. Apparently, Bartlett has not been reading Scott Sumner’s blog. Bartlett also said of all economists he finds Krugman to make the most sense on the current crisis. If so, then there is hope for Bartlett given Krugman’s admission that unconventional monetary policy can still work as noted above.

3. Bill Woolsely has had some great recent posts on monetary economics. First, he reminds us that we should not confuse money with credit. Second, he responds to Bryan Caplan’s post on velocity by, among other things, coming to defense of the equation of exchange as being more than a trivial tautology. I agree with him that the equation of exchange is useful in thinking about monetary economics and have used it before on this blog.

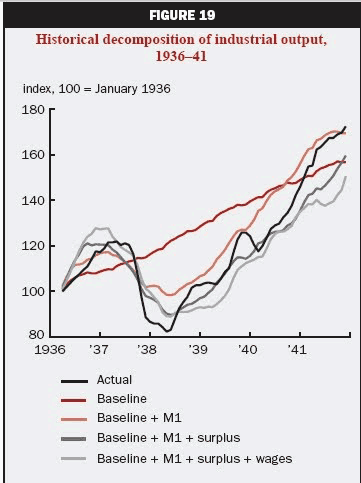

4. Francois R. Velde has a new paper on the recession of 1937. It is probably the best paper I have seen on the on this recession and makes a great policy implication for today: beware of tightening policy too soon in the recovery. Below is a figure from the paper that shows a historical decomposition of the recession. It comes from a vector autoregression that decomposes or attributes the forecast error for industrial production into non-forecasted movements in other series. Here, the other series are monetary policy as measured by M1, fiscal policy as measured by fiscal balance, and labor costs as measured by wages. In this figure, these series contribution to the forecast error–the difference between actual and forecasted (i.e. baseline) values– of industrial production is shown by their own colored lines. For example, the closer the baseline + M1 line is to the solid black line (i.e. actual industrial production) the more of the forecast error is explained by monetary policy:

This figure makes clear that tight monetary and fiscal policy explain most of the 1937 recession. Read the paper here.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply