Since October 2008 I have devoted much of my life to educating people about the need for further monetary stimulus. Thus I was pleased to see that in the past few days both Krugman and Yglesias have addressed the issue, although in somewhat different ways.

It shouldn’t be hard to convince liberals of the need for more monetary stimulus. So why is monetary stimulus discussed so rarely? I see the problem as more intellectual than ideological. Although I am a right-winger, my proposals would actually help Democrats more than Republicans, particularly in the 2010 and 2012 elections. But there is so much confusion about monetary policy that it is even hard for people to see policies that are in their own interest.

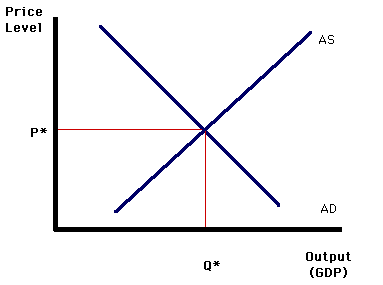

Let’s start with the confusion over the merits of setting an “inflation target,” which is discussed in both the Krugman and Yglesias columns. My concern is that people will misunderstand what is meant by this term, as we are used to thinking of inflation as a “bad thing.” Thus is sounds like inflation is the price we must pay for creating jobs. This ”trade-off” idea has some merit when the economy is faced with supply-shocks, but seriously distorts the real issues when the key problem is a demand shortfall. Even worse, the press often treats fiscal policy asymmetrically, suggesting that whereas an expansionary Fed policy would be designed to boost inflation expectations, fiscal stimulus is aimed at boosting real growth. But this creates a completely fictitious distinction; both policies have exactly the same objective; boosting aggregate demand. Look at the simple AS/AD diagram:

Both fiscal and monetary stimulus have exactly the same objective, to shift AD to the right, which will increase both prices and output. We would hope that more of the increase is output and less is prices, but that depends on the slope of the AS curve. Unfortunately, the press often suggests that monetary stimulus is aimed at raising prices and fiscal stimulus raises output, which tends to make fiscal stimulus look better.

This problem becomes even worse when rates have fallen to zero. Not one person in a hundred really understands how monetary policy works. The average guy on the street can picture how lower interest rates could boost spending, but has no understanding of the long run relationship between M and NGDP, where interest rates play no role. So to explain how monetary policy could work at the zero bound, we are forced to explain the mechanism using interest rates. Higher inflation expectations result in a lower real interest rate, which boosts aggregate demand. But that is equally true if the stimulus comes from the fiscal side. Higher expected inflation will lower real interest rates (if nominal rates are stuck at zero.)

Nick Rowe recently pointed out that the focus on interest rates is really just a “social construction. ” (I wish I had thought of that term first.) Here’s how I interpret Nick’s recent post. Central banks traditionally set the monetary base at a level that is expected to hit their policy goals. In my view the Fed has recently preferred about 5% NGDP growth, although they don’t state their goal in those terms. The Fed also finds it convenient to set a target for the overnight bank rate (the fed funds rate) in the hope that the target will create the amount of money necessary to hit their NGDP growth goals. When they need more money to hit their goals, they lower the fed funds target though open market purchases. But the “actual policy” in “reality” isn’t the interest rate target; it is open market operations, which change the size of the monetary base.

Normally the interest rate targets are just a convenient fiction. Ordinary people like to visualize things in terms of interest rates, and indeed so do many central bankers. Now suppose the fed funds target runs into a brick wall at zero percent. You cannot lower nominal rates below the zero rate earned on cash. Now it looks like the Fed has no more options. Of course they can still do all the OMOs they wish, and can still keep expected NGDP growing at about 5%. But the perception is that policy has failed, and that perception makes the Fed’s job much harder. People will think the Fed has “run out of ammunition,” and that they won’t be able to counter the fall in AD. Unless the Fed moves very aggressively to overcome those bearish expectations with an announcement of a very transparent and explicit policy, people will begin to fear deflation. And here’s the problem; once the public starts to fear deflation it is much harder for the Fed to run its monetary policy via changes in the monetary base. If deflation is expected then people and banks may hoard base money. So increases in the base won’t send out the signal that money is being eased. Hence you need something else. And what you really need is an NGDP target.

Unfortunately, economists are not used to thinking about NGDP. Instead they tend to think about inflation and real output, which are the two components of NGDP, and also the two variables that are affected by increased in aggregate demand. Why not have the Fed set an 6% real growth target? Why do economists speak in terms of an inflation target? It’s not because the Fed could not hit a 6% real growth target—I believe they could, for one year. But real growth targets were discredited years ago, because in the long run they leave the price level completely unanchored. So people talk in terms of inflation targets, not real growth targets.

With fiscal stimulus the language is completely different. Unlike with the money supply, there is no thought of permanently raising the budget deficit. The goal of fiscal stimulus is to merely pump up government spending for a year or two, in order to temporarily boost AD (and hopefully real output.) The implicit hope is that once recovery is achieved then monetary policy will take over. So the discussion of fiscal “multipliers” is often framed in terms of its effect on real output, not inflation.

Now take another look at the AS/AD diagram. Both fiscal and monetary stimuli aim to boost AD. In both cases it is assumed that prices and output will rise in the short run. In both cases the assumption is that in a deep recession output will rise much more than prices, and in both cases the assumption is that at full employment prices will rise much more than output. But because the language we use to describe these two types of stimuli are so different, fiscal stimulus “sounds” much more appealing. It sounds like fiscal stimulus is directly aimed at jobs, and monetary stimulus is aimed at inflation, with a sort of vague hope that we might get some jobs as a side effect.

I have always believed that monetary stimulus is much more effective than fiscal stimulus in a deep recession. That was certainly true for FDR—the dollar depreciation program had a much bigger impact than his fiscal stimulus. We can argue all day about “jobs saved vs. jobs created,” but the fact remains that fiscal stimulus has failed to achieve its objective in the US. The 10.2% unemployment rate is far too high, and President Obama would not be able to get another huge stimulus through Congress. Monetary stimulus can provide virtually unlimited increases in AD, and (if done through inflation or NGDP targets) it can do so without raising the budget deficit. It is our only realistic option for quickly and dramatically boosting AD. Indeed with monetary stimulus the only real danger is going too far, and ending up with hyperinflation. We are far from that point, however, for the foreseeable future the risk is too little spending, and too little inflation.

With nominal rates at zero, common sense suggests that monetary policy can’t do any more. That’s why it is so important to see Krugman clearly stating that, at least in principle, monetary policy is still the number one option. Liberals pundits should listen to Krugman’s economic analysis of monetary policy, and ignore his pessimistic political views on its feasibility. The Fed is a political institution that responds to public pressure. If the rest of Washington really understood the logic of Krugman’s views on inflation targeting, then the political pressure on the Fed would become almost unbearable. But first they need to understand why monetary policy is so powerful, and that requires unlearning some social conventions about interest rates and inflation.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply