Waiting for your smartphone to finish charging can oftentimes be a pain, especially when it just so happens that your battery gets completely drained at the most inconvenient of times. Now, a team of researchers at Drexel University led by Yury Gogotsi (PhD) may have figured out a way to effectively do away with this problem. In other words, the days of waiting for hours to let your phone recharge may be coming to an end.

As it is, the best features of a battery and a supercapacitor have yet to be combined. A battery can store huge amounts of energy, but recharging it takes a lot of time. On the other hand, a supercapacitor can charge and dole out energy much faster than batteries, but it can’t store as much energy as a battery can.

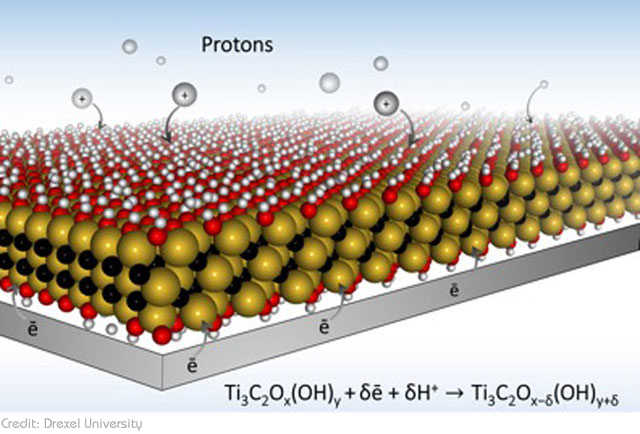

The new design invented by the Drexel University team bridges this gap. Using the highly conductive 2D material MXene to develop a new type of electrode, the team has managed to combine the superior storage capacity of a regular battery with the extremely fast charging capacity of a supercapacitor. If all goes well, this could easily pave the way for quick-charging devices. And by quick we mean devices that charge in only a matter of seconds. According to Dr. Gogotsi, they were able to demonstrate ‘charging of thin MXene electrodes in tens of milliseconds’.

Aside from using a highly conductive material, the team also zeroed in on the structure of the electrode.

Typically, charge is stored by holding ions (electrically charged particles) in ports referred to as redox active sites. The more ports there are, the more energy the battery can store. The new electrode design doesn’t just feature more ports. The ports are also ‘macroporous’, meaning, they are filled with small openings and these openings make it possible for more of the ions to get into the ports at the same time. And this is what expedites the charging time.

As explained by the paper’s lead author Maria Lukatskaya, the main problem that slows down charging of traditional batteries and supercapacitors is the ‘tortuous path’ that ions have to go through in order to get to the ports. The limited path doesn’t simply slow down the process; sometimes, it also results in just a few electrons actually making it to their destination. The ‘macroporous’ design of their electrode solves this problem. Instead of a ‘single lane’, the multiple openings on their electrode provide ‘multi-lane, high-speed highways’ that allow ions to move freely and reach their destination faster.

“If we start using low-dimensional and electronically conducting materials as battery electrodes, we can make batteries working much, much faster than today. Eventually, appreciation of this fact will lead us to car, laptop and cell-phone batteries capable of charging at much higher rates — seconds or minutes rather than hours,” Gogotsi said.

The paper detailing the research was recently published in the journal Nature Energy.

Leave a Reply