According to Calvin Trillin (or, more accurately, the probably-at-least-semi-fictional interlocutor he meets at a bar in Midtown), the financial crisis was caused by smart people going to work on Wall Street. In the old days, the story goes, it was the lower third of the class that went to Wall Street, and “by the standards that came later, they weren’t really greedy. They just wanted a nice house in Greenwich and maybe a sailboat. A lot of them were from families that had always been on Wall Street, so they were accustomed to nice houses in Greenwich. They didn’t feel the need to leverage the entire business so they could make the sort of money that easily supports the second oceangoing yacht.”

Then, however, as college debts and Wall Street pay grew in tandem, the smart kids started going to Wall Street to make the money, leading to derivatives and securitization, until finally: “When the smart guys started this business of securitizing things that didn’t even exist in the first place, who was running the firms they worked for? Our guys! The lower third of the class! Guys who didn’t have the foggiest notion of what a credit default swap was.”

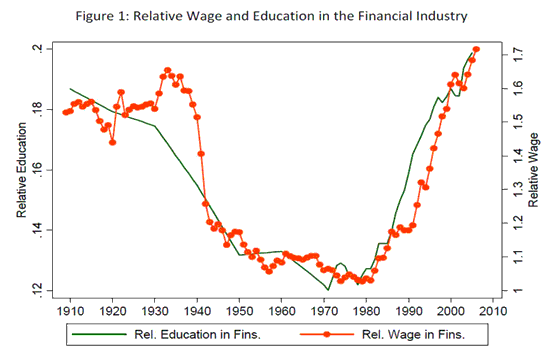

It’s a cute story. But there may be an element of truth to it. In their well-known paper, “Wages and Human Capital in the U.S. Financial Industry: 1909-2006,” Thomas Philippon and Ariell Reshef measured the relative wage and relative educational levels of workers in the financial sector over the last century. The picture looks like this:

The relative wage I knew about — that’s something we also charted in our Atlantic article. The relative education I did not know about (although there was lots of anecdotal evidence).

Now, Philippon and Reshef calculate relative education using the share of workers with more than a high school education; the left axis is the difference between this share in the financial sector and in nonfinancial industries. So all college students are treated equally — there’s no differentiation by where you went to college or how you did there. But there’s no reason not to think that, as finance became more complicated and required more math aptitude (see Figure 3 in the paper), the level of academic achievement went up as well.

I read somewhere that of the CEOs of the largest banks, only Vikram Pandit at Citigroup (NYSE:C) was a true “quant,” and he only came in when Citi bought his hedge fund in 2007, after the bulk of the damage was done. (I’m not endorsing Pandit’s job as CEO, only saying that the mess was there before he arrived.) So there probably was this situation where the executive ranks were filled with old-style relationship-builders and dealmakers, and the increasingly quantitative traders were doing things they didn’t understand. A similar story has been told about Salomon under John Gutfreund in the 1980s (and LTCM under John Meriweather in the 1990s).

Technology firms also face a similar problem. In technology, as in most businesses, the way to make it to the top is through sales, so you end up with a situation where the CEO is a sales guy who has no understanding of technology and, for example, thinks that you can cut the development time of a project in half by adding twice as many people. I have seen this have catastrophic results. Even when you don’t have the generational issue that Trillin talks about, the problem is that the sociology of corporations leads to a certain kind of CEO, and as corporations become increasingly dependent on complex technology or complex business processes (for example, the kind of data-driven marketing that consumer packaged companies do), you end up with CEOs who don’t understand the key aspects of the companies they are managing. And the underlying problem is that, for all the blather that CEOs and boards spit out about succession planning and the importance of people, the fact remains that the market for CEOs is deeply flawed, as shown for example by Rakesh Khurana.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply