How important would an economic downturn in China be for the United States?

Paul Krugman reviews some of the reasons why the United States perhaps shouldn’t worry too much:

China’s economy, while big, is still a small fraction of the global economy– about 15 percent at market exchange rates…. Chinese imports from the rest of the world are less than 3 percent of the ROW’s GDP. Suppose China experiences a 5 percent slump in its own GDP; given an income elasticity of 2, which is reasonable, this would mean a 10 percent fall in imports– but that’s a shock to the rest of the world of just 0.3 percent of GDP. Not nothing, but not that big a deal.

I’ve long believed that to understand business cycles we need to consider not just net flows but also gross interdependencies. A downturn in China will affect some businesses much more than others. If specialized labor and capital do not easily move to other sectors, that can end up having significant multiplier effects.

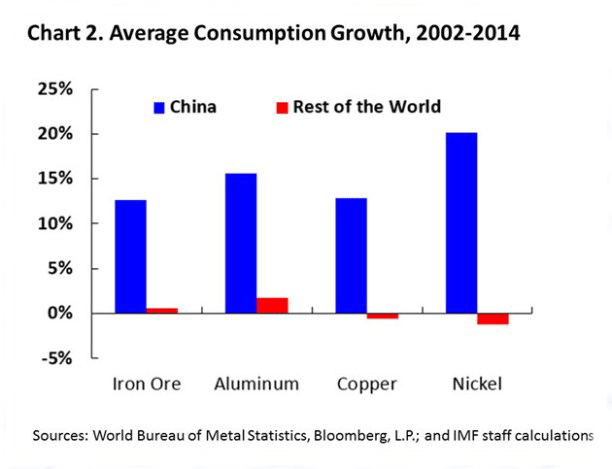

For example, while China may only account for 15% of world GDP, it has been a huge factor in commodity markets over the last decade. According to EIA data China accounted for 55% of the increase in global petroleum consumption between 2005 and 2013. IMF economists Arezki and Matsumoto note that China now accounts for about half of global consumption of iron ore, aluminum, copper, and nickel.

Source: IMF Direct

U.S. exports of goods and services to China in 2014 were $167 billion, only about 1% of U.S. GDP. But U.S. investment in mining structures (explorations, shafts, and wells) amounted to $146B at an annual rate in 2014:Q4. By the second quarter of this year that number was down to $89B, largely a result of cutbacks in the U.S. oil patch. This means that in the absence of offsetting gains elsewhere, this development alone has already subtracted about 0.3% from U.S. GDP.

Of course, lower commodity prices will force layoffs for oil companies and miners but leave more money in the hands of consumers. However, additional spending from that channel has been more modest than many of us were anticipating.

Another concern comes from financial linkages. A Chinese downturn will unquestionably be a big hit for certain financial institutions. Exactly who those will be and what it means for the rest of us, I don’t know. As Warren Buffett observed, “you only find out who is swimming naked when the tide goes out.”

The bottom line is that an economic slowdown in China already is a very big deal for some U.S. workers and businesses. I don’t know what the ultimate implications for the U.S. of a significant recession in China would be.

But things I don’t know cause me to worry.

Leave a Reply