Artificial trans fat is omnipresent in the global food chain, but the medical consensus is that it increases the risk of developing cardiovascular diseases such as heart disease and stroke. Between 2007 and 2011, New York City and six other county health departments implemented bans on trans fat in restaurants. This column presents the first evaluation of the effect of these bans on cardiovascular disease mortality rates.

The use of artificial trans fat or partially hydrogenated oil – which is industrially produced by adding hydrogen gas to liquid vegetable oil – is widespread across the world’s food production chains and service industries. Aside from the fact that it has the same caloric value as any other fat, there are no known health benefits to consuming artificial trans fat. The food industry prefers using trans-fat-containing oils to healthier oils because it is cheap, it increases the shelf life of food products, it promotes flavour stability, and it improves the texture of food. Artificial trans fat is typically found in shortenings, margarines, fried fast foods, baked goods, and snack foods (Eckel et al. 2007).

But how much do we really know about artificial trans fat? Well, we know that eating foods containing artificial trans fat increases the risk of developing cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) such as heart disease and stroke, because it raises bad cholesterol and lowers good cholesterol (Mozaffarian et al. 2006). Thus artificial trans fat is worse than saturated fat, which increases both good and bad cholesterol. The American Medical Association has recently supported the Food and Drug Administration’s recommendation to eliminate artificial trans fat from the US food supply (AMA 2013). Some European countries (e.g. Denmark and Switzerland) have also recently made efforts to eliminate artificial trans fat from their food supply.

What we do not know, however, is how much of an effect banning artificial trans fat will have on public health.

The impact of banning artificial trans fat on cardiovascular health: First causal evidence

In a recent paper (Restrepo and Rieger 2014), we exploit the fact that New York City and six other county health departments implemented trans fat bans in all food service establishments that require a permit to serve food between 2007 and 2011. This allows us to assess whether artificial trans fat consumption has a causal impact on cardiovascular health and CVD mortality rates.

Using variation in the artificial trans fat content in the local food supply of a total of 11 New York State counties resulting from the policy mandate, we find that trans fat bans caused a 4% reduction in deaths attributable to CVD. We also find evidence that the reduction in mortality caused by trans fat bans is mostly driven by individuals who are at the greatest risk of dying from CVD, namely, senior citizens.

How were CVD mortality rates trending before trans fat bans were implemented?

A natural question that arises is: Did the CVD mortality trends in counties that implemented trans fat bans differ from those in counties that never implemented them? If the trends before the bans were similar, then the counties that did not implement the bans may be viewed as a suitable ‘control group’, and as a good counterfactual for the CVD mortality trajectory that the ‘treatment group’ would have followed in the absence of trans fat bans.

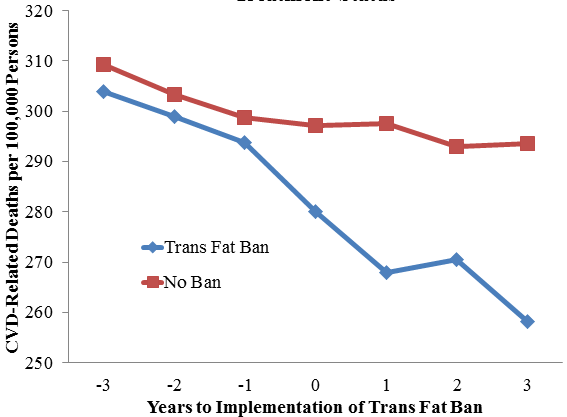

We address this issue by normalising each treatment county’s trans-fat-ban implementation year to zero and plotting CVD mortality rates by treatment status. Figure 1 shows that the CVD mortality rates in ‘treatment’ and ‘control’ counties were trending in a very similar fashion before trans fat bans were implemented by ‘treatment’ counties. A clear downward break from trend is observed in the implementation year for ‘treatment’ counties, whereas the trend in ‘control’ counties appears to follow its pre-implementation-period trajectory.

Figure 1. Trends of cardiovascular-disease-related mortality per 100,000 persons by treatment status

Notes: Authors’ calculations based on Vital Statistics of New York State. These are mean CVD mortality rates by county and year. We assume that a ban is in effect if the law has been effective for at least six months in a given year. Each county’s implementation year is normalised to zero.

This figure alone suggests that trans fat bans were effective in reducing CVD mortality rates. However, we conduct a regression analysis to account for the fact that ‘treatment’ counties are seemingly ‘healthier’ (as measured by lower CVD mortality rates throughout the study period) and to rule out the possibility that the relationship between trans fat bans and CVD mortality rates is merely a spurious correlation.

How many lives have trans fat bans saved?

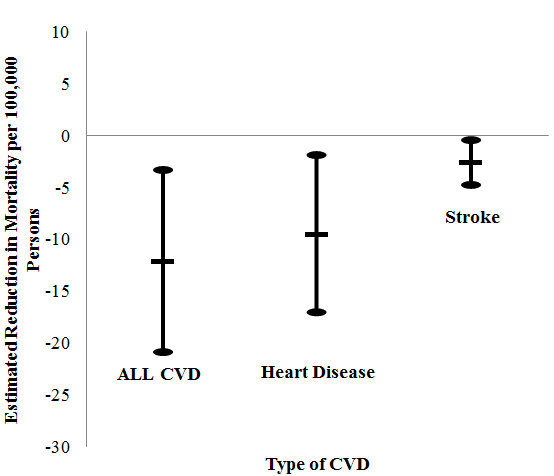

Figure 2 shows Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) estimates of the reduction in overall CVD mortality rates, heart disease mortality rates, and stroke mortality rates caused by trans fat bans, along with their corresponding 95% confidence interval bands. We find that trans fat bans reduce CVD deaths by 12 per 100,000 persons, reduce heart disease deaths by 9.5 per 100,000 persons, and reduce stroke deaths by 2.6 per 100,000 persons. (These are estimated reductions of about 4.4%, 3.9%, and 8.5% relative to our sample means.) The estimated reduction in CVD is economically important – for instance, it is about twice the size of the mortality rate per 100,000 persons for cirrhosis of the liver in New York State in 2006.

Figure 2. Trans fat bans and cardiovascular disease mortality by type of disease

Notes: Authors’ calculations based on Vital Statistics of New York State. These estimates are based on regressions of (log) CVD, heart disease, and stroke mortality rates on the following independent variables: treatment dummy (1 if a county implemented a trans fat ban, 0 otherwise), county level unemployment rate and (log) personal income per capita, and a dummy for New York City interacted with a dummy for years 2010–2012 to account for hospital-level interventions aimed at improving the accuracy of cause-of-death reporting. N = 682, standard errors are always clustered at the county level.

To get a better sense of the magnitude of our estimates, consider the following back-of-the envelope calculation. New York State counties that implemented trans fat bans over our study period had 34,215 heart-disease-related deaths in 2006, so our estimates indicate that, on average, implementation of trans fat bans prevented about 1,300 (3.9% × 34,215) heart-disease-related deaths per year. Assuming a discount rate of 3%, Aldy and Viscusi (2008) find that the cohort-adjusted Value of a Statistical Life-Year is about $302,000. Even if fatal heart attacks cause only one year of life to be lost, the fatal heart attacks prevented by trans fat bans can be valued at about $393 million annually.

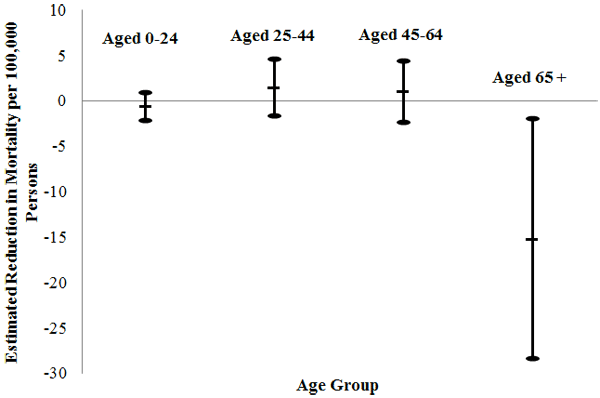

Figure 3 shows OLS estimates of the reduction in all-cause mortality rates caused by trans fat bans by age group, along with their corresponding 95% confidence interval bands. We find that the estimated effects of trans fat bans on total mortality rates are small in magnitude for non-seniors, and we can never reject the null hypothesis that these estimates are statistically equal to zero. In contrast, we find that trans fat bans have a large negative effect on the all-cause mortality rates of senior citizens, which we estimate to be a reduction of about 15 per 100,000 persons. Note that this estimate is very similar in size to the estimated reduction in CVD mortality rates we presented in Figure 2. This suggests that most of the impact of trans fat bans on total mortality is driven by its impact on CVD mortality.

Figure 3. Trans fat bans and total mortality by age group

Notes: Authors’ calculations based on Vital Statistics of New York State. These estimates are based on regressions of (log) CVD, heart disease, and stroke mortality rates on the following independent variables: treatment dummy (1 if a county implemented a trans fat ban, 0 otherwise), county level unemployment rate and (log) personal income per capita, and a dummy for New York City interacted with a dummy for years 2010–2012 to account for hospital-level interventions aimed at improving the accuracy of cause-of-death reporting. N = 682, standard errors are always clustered at the county level.

Conclusions

Our analysis reveals that trans fat bans are effective in reducing deaths attributed to CVD such as heart disease and stroke. European countries such as Denmark and Switzerland, as well as many local and state jurisdictions outside of New York State, have also passed laws restricting the amount of artificial trans fat that food production and service industries are allowed to use. In 2013, the Food and Drug Administration made a preliminary determination to remove artificial trans fat from its Generally Regarded as Safe database, which is likely to eliminate it from the US food supply in the coming years.

Heart disease is the leading cause of death in New York State and in the US, and stroke is not far behind. In the US, the total cost of the major types of CVD was estimated to be about $444 billion in 2010, and treatment of these diseases accounts for nearly 17 cents of every dollar that is spent on health care (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2011). The New York experience can prove valuable for many public health authorities around the globe. Eliminating artificial trans fat – which has no known health benefits – from the global food supply has the potential to lead to substantial reductions in the loss of life and health care costs associated with CVD.

References

•Aldy, J E and W K Viscus (2008), “Adjusting the Value of a Statistical Life for Age and Cohort Effects”, Review of Economics and Statistics, 90(3): 573–581.

•American Medical Association (2013), “AMA: Trans Fat Ban Would Save Lives”, 7 November.

•Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2011), “Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention – Addressing the Nation’s Leading Killers: At a Glance 2011”.

•Eckel R, S Borra, A Lichtenstein, and S Yin-Piazza (2007), “Understanding the Complexity of Trans Fatty Acid Reduction in the American Diet”, Circulation, 115: 2231–2246.

•Mozaffarian D, M B Katan, A Ascherio, M J Stampfer, and W C Willett (2006), “Trans Fatty Acids and Cardiovascular Disease”, New England Journal of Medicine, 354: 1601–1613.

•Restrepo, B and M Rieger (2014), “Trans Fat and Cardiovascular Disease Mortality: Evidence from Bans in Restaurants in New York”, European University Institute Max Weber Programme Working Paper 2014/12.

Leave a Reply