I have a Facebook account, but I almost never post. I also have a Linkedin account, but it is a not premium, largely because I am not that interested in finding out who is looking at my profile or endorsing me (often for skills I don’t have). I do have a Twitter account and while I don’t post very often, I just like the ease with which it lets me bug thousands of people. All of this is of course a lead in to the story that I am sure will dominate the financial news for the next few weeks: Twitter is planning its initial public offering and everyone has an opinion on what it will be priced at.

While I will try to value Twitter when the time is right, I am going to use this post to price Twitter, not value it, for three reasons. First, Twitter’s financial statements are still inaccessible, a consequence of the JOBS Act (passed last year) that allows “emerging companies” (with revenues < $1 billion) to use a confidential process for filing with the SEC. Unlike some who are worked up about the resulting lack of transparency, I am not in high dudgeon about this non-disclosure. The company will have to provide a full prospectus a few weeks before the shares are priced (and offered) and there will be plenty of time for me to do my due diligence. Second, the lead investment bank (Goldman Sachs) will be pricing the company for the offering, not valuing it, and I want to use this post to take a look at that process. Third, if you choose to play this IPO game, to win, you have to be able to play the pricing game well, not get the value right.

The tools/inputs of Pricing

To value a business, you start with raw data from a company’s financial statements, draw on measures of risk and operating efficiency for the business in which it operates, make estimates for the future and use a valuation model (with my preference being for a discounted cash flow (DCF) model). To price a company, you draw on a different set of inputs and tools, with the following standing out:

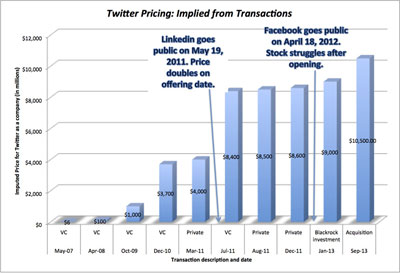

1. Current price: This may sound circular but the key input into the pricing process is the current price of the asset. After all, in pricing, you are accepting the market’s judgment of price as the only number that ultimately matters. With publicly traded companies, this dependence on the price takes the form of charts and technical indicators, which can then be mined for clues about future price movements. Looking at a still private company like Twitter, this approach may seem like a non-starter, since it has no public market, but there have been transactions in the past that provide clues about its price. Some of these transactions involve venture capital investments, where you can extrapolate from the investment and the share of the company received by the venture capitalist to the overall price of the company is. Others involve private sales by one investor to another, where again the transaction price provides clues as to the the overall price. The following graph, drawn mostly from a Wall Street Journal news story on the company, imputes prices for Twitter based upon trades over the last few years on the company’s equity.

(click to enlarge)

Note that the imputed price of equity in Twitter was $100 million in 2008 and that the price has surged over the last three years, rising from $ 1 billion in late 2009 to $ 9 billion early this year and $10.5 billion a week ago. Much of the surge occurred in the latter half of 2011, after Linkedin went public to a rapturous market response in May of that year.

Is it okay to extrapolate from isolated transactions to overall price? Yes and no. There is information in the transactions but the price estimate can be skewed by three factors. The first is that the transactions may not be at arms length, resulting in a price that has less to do with what the transactors think the business is worth to them and more to do with side objectives (control, taxes). The second is that even in an arms length transaction, the value that you impute may not be reflective of the fair price for a publicly traded company but may reflect instead the pricing of a private, illiquid business (which is lower). The third is unless the most recent transactions occurred very recently, the price you get is stale and will have to get updated to reflect both market and sector developments. With Twitter, none of these concerns rise to a serious level: the venture capital transactions are motivated by profit, the company has been priced as company that will go public for the last two or three years and there are at least two recent transactions from this year. The first reflects the sale of 15% of the company to Blackrock, with an imputed price of $9 billion for the company. That transaction was in January 2013 and both the market and social media companies have risen in price, since then; the S&P 500 is up 20% since January and Facebook & Linkedin, the two social media companies that are viewed as closest to Twitter, have gone up even more over the same time period (Linkedin has doubled and Facebook has gone up about 67%). Applying even the market change (20%) to Twitter would yield a value of $10.8 billion, and applying the social media appreciation number would increase that value to $16-$18 billion. In September 2013, just a few days ago, Twitter bought MoPub, a mobile advertising exchange, and issued stock to cover the transaction cost. Imputing the value of Twitter from the share issue leads to an imputed price for Twitter estimate of at least $10.5 billion. Thus, just based on these two private transactions, the price of Twitter should be at least $10.5 billion and perhaps a bit more.

2. Relative value: The other commonly used tool in pricing is relative value, where you set the price for an asset by looking at the prices at which comparable companies are traded at in the market. The process of applying this approach to price a company like Twitter can be complicated by two factors.

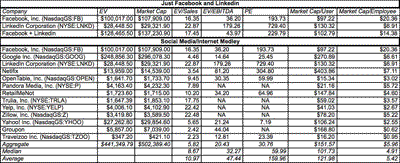

a. Scaling variable: Since the units into which you divide value (number of shares) is by its nature arbitrary, you need to scale the price to a common variable. That, of course, is the role of a multiple, whether it be PE, Price to Book or EV/Sales. In the context of young, growth companies, where earnings and cash flows are often negative and book value is meaningless, analysts either focus on revenues, and/or scale the price to some measure of operating success (users, subscribers etc). With Twitter, a revenue multiple can be utilized to estimate value, even if its financial statements report a net loss or EBITDA for the year. The table below provides the multiples estimated in September 2013 for Facebook and Linkedin in the first two rows, as well as a broader sample of firms that loosely derive their revenues from online services (though some like Netflix are subscription based and some like Pandora get a mix of advertising and subscription based revenue):

(click to enlarge)

All the normal caveats apply. The accounting numbers reflect trailing 12 month estimates, but in companies like these, these numbers will change dramatically from period to periods, as will the number of users and employees. The number of users disguises wide differences among them, with heavy, mild and completely idle users aggregated together and sometimes double or triple counted. The value per users will be skewed by differences in business models, with companies like Netflix that have subscription based revenues registering much higher values.

Even with the very limited public numbers that you have for Twitter, you can start estimating prices, using these multiples. For instance, if the news stories that peg Twitter’s most recent twelve-month revenues at $583 million are right, you could apply the revenue multiple of 17.45, that its two closest competitors ($FB & $LNKD) trade at, to arrive at a value of $10.17 billion, fairly close to the most recent transaction price. (Twitter’s cash balance would have to be added to this number to get to a market capitalization.)

Twitter’s estimated enterprise value = $583 * 17.45 = $10.17 billion

Before you get too excited about this convergence, recognize that applying the median EV/Sales ratio of 8.67 for the social media medley to Twitter’s revenues yields a value of $5.05 billion, making the $10 billion plus numbers being bandied about look awfully high.

Twitter’s estimated enterprise value = $583 * 8.67 = $5.05 billion

Just to round out the estimates, you could always apply the multiple of $130.32/user that investors are paying collectively for Linkedin and Facebook to Twitter’s 240 million users (I have seen wildly varying estimates of this number with some estimates ranging up to 500 million) yields a price of close to $25 billion.

Twitter’s estimated market capitalization = $130.32 * 240 = $24.4 billion

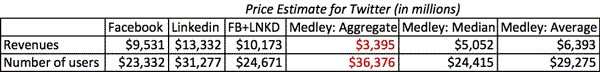

I have estimated a range of prices for Twitter based upon the different combinations (multiple, choice of comparable firms, averaging approach):

Which one of these is the right price? That depends on what your priors are about Twitter and perhaps what you are trying to convince me to do. If you believe that it is a great company that will also be a great investment, you will go with the combinations that yield the higher number. If you are convinced that this is the next bubble that will burst, you will use the lowest values to justify selling short or warning people away from the company. It is no wonder that equity salespeople latch on to this approach. All you have to do is find the right mix of multiple and comparable firms and you can back up any sales pitch (that the company is cheap, expensive or correctly priced) you want to make about any company. If you are on the other side of this sales pitch, it has be caveat emptor.

b. Current versus Forward Numbers: To the extent that your multiples are skewed or meaningless because current values for earnings, book value and capital expenditures are small and meaningless (in terms of forecasting future values), you can try to forecast the values for each of these items and apply a multiple (based usually on what other publicly traded companies are trading for today) to get the estimated value in the future. Getting from that future value to value today can be dicey, as I illustrated in my last post on Tesla (TSLA), as risk, time value and dilution all eat into the terminal value. It is also worth noting that while this may be easy to do for a young growth company in a sector where most of the competitors are mature, it will be difficult to do with Twitter, where the lead competitors, Facebook and Linkedin, are also in high growth and will change over time.

The Drivers of Price

Just as the tools and drivers of pricing are different from those of value, the drivers of price vary from the drivers of value. Thus, while value is determined by cash flow, growth potential and risk, price is determined by a different set of variables:

- Momentum/Mood: Much as intrinsic value investors tend to disdain momentum, it remains true that momentum is one of the most powerful forces driving returns with stocks. Studies indicate that over shorter time periods, momentum based investing often delivers much better results than fundamental based investing. For some stocks, especially those in “hot’ sectors, momentum is the key driver of prices, drowning out news about the fundamentals.

- Incremental news: Once you accept the pricing proposition that the market price is what it is, the key to winning at the pricing game becomes forecasting changes in price rather than assessing whether the current price is right. As a consequence, your focus on news stories will become incremental and each news story will be assessed in terms of how it will change the price, rather than how it will affect overall value.

- Liquidity: If you invest based on long term value, you can afford to put liquidity on the back burner for two reasons. First, the cost of illiquidity (higher transactions costs) can be spread over your long holding period, reducing its impact on your returns. Second, since you are not investing on momentum and not as dependent on timely trades for your profits, you can afford to wait to buy or sell, rather than have to do so in the middle of market chaos. If you are trying to make money on pricing, liquidity or the lack of it can not only make the difference between making and losing money, but in extreme cases, can lead to disaster (especially if you have a pricing strategy accompanied with high high leverage).

The Dangers of Pricing

The pricing game can generate large profits in short periods but it comes with a warning label. It is not for the faint hearted, since it is accompanied by risk. The market can make mistakes in the aggregate:

- Markets can be wrong in the aggregate: I know that active investors view those who believe that markets are efficient (I don’t…) as eggheads or worse. It is worth noting, though, that many of these same active investors are “pricers”, who pick stocks based upon multiples and comparable firms. In effect, they are assuming that markets are right in the aggregate, but make mistakes on individual companies, which would make them semi-believers in market efficiency. If markets are wrong in the aggregate, you can be right in your relative assessment (that a stock looks cheap relative to its competitors) and still lose large amounts (if they are all over priced).

- Mood shifts (inflection points): To the extent that price is driven by momentum and mood, shifts in that mood can very quickly turn profits to losses. The key to winning at the game therefore becomes detecting inflection points (where positive momentum turns to negative momentum) and altering your investment strategy. This is the promise of charting and technical analysis, where price and volume patterns yield clues about future momentum shifts. Even the best indicators, though, often fail at this task. It is also worth noting that momentum is fragile and based partly on illusions. If bankers show contempt for the process and its players (as I think Facebook and its bankers did at the time of their IPO), the momentum may very well shift.

- Taxes and transactions costs: As a general proposition, playing the pricing game requires you to have a shorter time horizon and to trade without regard to tax consequences. Thus, if you buy a momentum stock and profit over the ten months that you hold it but you detect a shift in momentum, you will sell the stock and take your profits, even though you face a much tax bill as a US investor (if you had held for a year, you could have qualified for capital gains).

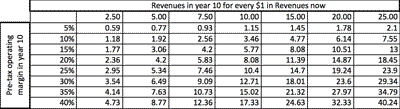

- Implied assumptions: Many analysts and investors who use multiples justify that usage by arguing that intrinsic valuation require too many assumptions and that pricing/relative valuation does not. I would argue that any multiple has embedded in the same assumptions but that they are more implicit than explicit. Take Twitter, where the key assumptions are about how much revenues will have to grow and what the target operating margins will be on these revenues. In the table below, I have estimated the multiple of revenues that you would be willing to pay for any company, given how your expect revenues to change over the next ten years and the operating margin in year 10. For simplicity, I have left the risk (cost of capital) and quality of growth (reinvestment) unchanged. (My hypothetical company had a cost of capital of 12% to start, moving towards an 8% cost of capital in perpetuity and a return on capital in 12% after year 10.)

(click to enlarge)

This table can be used in two ways. If you believe, for instance, that Twitter’s revenues will increase ten-fold (from $538 million to $5.38 billion) over the next decade and that its target margin will approach 30%, you would be willing to pay 12.71 times Twitter’s current revenues for the company (12.71*583 = $7,409 million). Conversely, if you are intend to pay 20 times current revenues (about $11.6 billion) for Twitter, you would need revenues to increase fifteen-fold over the next decade and margins to converge to about 32% in year 10. (I will update this table when Twitter’s financial statements come out.)

A Cynical View of the Twitter IPO Pricing Game

If you decide to play the pricing game, you will have lots of company. In fact, I would argue that much of what passes for valuation in investing is pricing. In an IPO, in particular, how a company is priced for a public offering and what happens in the after market, at least in the months following the offering has more to do with pricing than value.

So, here is my take on what will happen. Goldman Sachs will start with the latest transaction value for Twitter, approximately $10.5 billion, and adjust it up for the improvement in both the overall market and in social media companies (especially Facebook) since the start of the year. They will then create a sales pitch for that value, using the pricing of other social media companies (Facebook and Linkedin, in particular) to argue that Twitter is a bargain at their estimated price. (My guess is that they will focus on the number of users and how Twitter looks like a bargain on that basis.) That sales pitch will be tried out on institutional investors for effect, with the salespersons’ ears especially attuned to either too much enthusiasm from these investors (a sign that the price was set too low) or to little (a signal that it is et too high). The institutional investors, not having a clue about the fair value of Twitter, will talk to each other and ratchet up or down their own enthusiasm based upon what they sense in their compatriots. The investment bank, having tweaked the price based on investor reactions will then do a discounted cash flow valuation, reverse engineered to deliver that price as the final value. (A good test of their valuation skills will be in how well they hide this reverse engineering to make it look like the valuation led to the pricing rather than the other way around). Finally, having learned from the Facebook fiasco that it is better to under price rather than over, they will knock off about 15% off their estimated price/value to set the offering price. At the risk of being hopelessly wrong in hindsight, I would be very surprised if I saw Twitter priced lower than $10 billion or higher than $15 billion, unless there is a major market disturbance. (As a point estimate, I would guess that it will be priced around $12 billion. In fact, let’s start a shared Google spreadsheet of our price guesses. They are based on nothing more than rumor and minimal information, but why let that stop us?)

Am I being cynical? Perhaps, but I think we would all be better served if the process was stripped off its veneer of value. If we honestly faced up to the reality that this is an exercise in pricing and not valuation, the bankers can dispense with their quasi DCF models that they have no belief in, focus on pricing the stock and recognize that they will be judged on their pricing and deal making skills, not their valuation expertise. The issuing companies will recognize that their role in the process is to act as facilitators in the marketing, packaging the company like a shiny present and providing incremental news that pushes the price in the right direction. The investors who decide to play the IPO game or invest in the after market will not waste their time and resources estimating value, since their success or failure will come from how well they gauge momentum shifts and time their exits. I will value Twitter, when the financials are released and the time is right, but my advice to you is that you ignore my valuation, if you are playing the IPO game. The market for Twitter will little note nor long be concerned with my or anyone else’s assessment of value.

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply