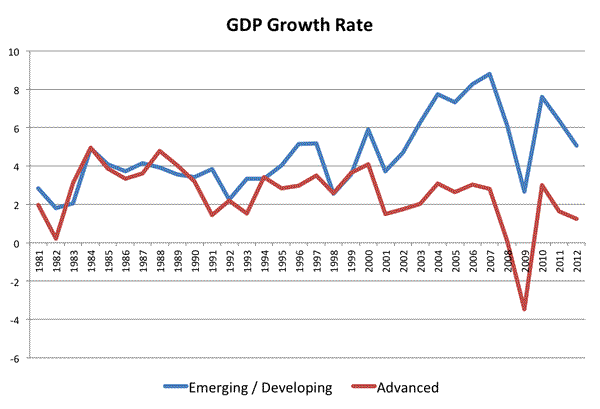

There is an increasing debate about the ability of emerging markets to continue growing at the pace at which they have been growing over the last years. The last decade has been remarkable for emerging markets as a group. The chart below compares the growth rate of (real) GDP for the group of advanced economies and for the group of emerging and developing economies (definitions and data coming from the IMF).

After decades where emerging markets were growing at best at the rate of the advanced economies, since 2000 we see a clear gap in growth rates and a strong process of convergence or catching up. The difference is large, as large as 4 or 5 percentage points in many years.

There are many potential reasons why the fate of emerging markets changed since 2000. From a regional perspective Asia was already doing well in previous decades and continued to grow at a strong or even stronger rate. Some countries in Latin America started growing at decent rates after really weak performance in the previous decades. And African growth rates have been at the highest level in many years.

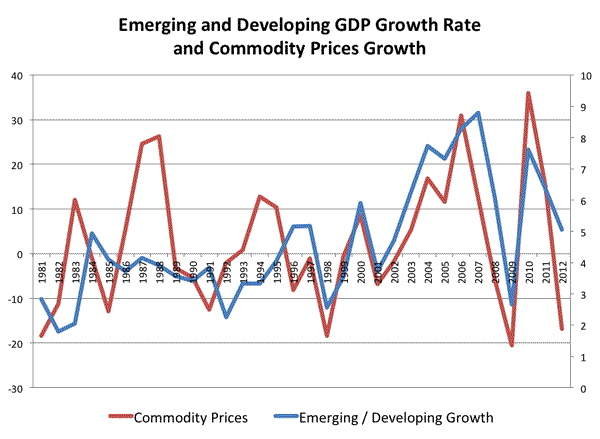

During those years we have also seen another strong trend in the world economy, the fast growth in the prices of commodities. The fact that these prices have increased can be seen as the outcome of strong growth in the world (fueled by emerging markets). But the causality also runs backwards for some of these countries: it was the strong demand coming from certain economies that pushed prices up and allowed those countries that produce commodities to see growth finally happening.

The data shows that indeed, the phenomenal growth in emerging markets post-2000 coincided with positive developments in commodity prices. The figure below compares the growth in GDP of emerging and developing countries (from the previous figure) with the growth in the price of commodities during the same years [Note: the series used for commodity prices is Commodity Industrial Inputs Price Index includes Agricultural Raw Materials and Metals Price Indices from the IMF; including food prices or oil prices to the index does not change the correlation at all].

What is remarkable about the data is not that there is a strong correlation in the post-2000 period but also that this correlation has become much stronger than before. For the reasons outlined above it makes sense that these two series are correlated, what is interesting is that the correlation has become strong in the years where growth in emerging markets has taken off. And this cannot simply be the fact that emerging markets matter more in the world economy (and therefore have a strong influence on the price of commodities). If this was the case we would simply expect the other countries (advanced) to have a much stronger influence in the earlier years, but this is not the case.

To explain the correlation above we probably need a combination of qualitatively different growth during these years that is putting demand pressure on prices while at the same time the producers of commodities (mostly emerging markets) benefit from this demand and grow at higher rates. But regardless of the explanation, it is important to realize how the fate of emerging markets and commodities prices is much more linked than in the past.

Leave a Reply