If you are a Fed watcher, you have to love a day like this. The minutes of the most recent FOMC meeting tended toward the dovish side, sufficiently so that my conviction on September wavers somewhat. That said, I would say that the minutes did little to clear the murky water that is Fed policy. Consensus about the future path of policy appears to be lacking, with “several” on one side of an issue and “many” on the other. The muddled approach to communications is also evident. But the fact that they made a relatively bold move despite the initial lack of consensus suggests that a strong hand pulled them in that direction. Who could that be? Little doubt that it was Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, who also felt like it was necessary to lay down the law a little tonight and make clear what market participants have been unwilling to hear: Quantitative easing and interest rates are two separate policies.

FOMC participants had a generally optimistic economic outlook:

In their discussion of the economic situation, meeting participants generally indicated that the information received during the intermeeting period continued to suggest that the economy was expanding at a moderate pace. A number of participants mentioned that they were encouraged by the apparent resilience of private spending so far this year despite considerable downward pressure from lower government spending and higher taxes….

….Most participants anticipated that growth of real GDP would pick up somewhat in the second half of 2013. Growth of economic activity was projected to strengthen further during 2014 and 2015, supported by accommodative monetary policy; waning fiscal restraint; and ongoing improvements in household and business balance sheets, credit availability, and labor market conditions.

That said, they were concerned that the weaker growth numbers would catch up to the labor markets:

However, some participants noted that they remained uncertain about the projected pickup in growth of economic activity in coming quarters, and thus about the prospects for further improvement in labor market conditions, given that, in recent years, forecasts of a sustained pickup in growth had not been realized.

They believed low inflation was largely transitory, but added this:

In contrast, many others worried about the low level of inflation, and a number indicated that they would be watching closely for signs that the shift down in inflation might persist or that inflation expectations were persistently moving lower.

If I stop here, I would tend to conclude that there was sufficient uncertainty about the economic outlook, especially given low inflation, that talk of winding down asset purchases was premature. But then begins the communication discussion:

Participants discussed how best to communicate the Committee’s approach to decisions about its asset purchase program and how to reduce uncertainty about how the Committee might adjust its purchases in response to economic developments. Importantly, participants wanted to emphasize that the pace, composition, and extent of asset purchases would continue to be dependent on the Committee’s assessment of the implications of incoming information for the economic outlook, as well as the cumulative progress toward the Committee’s economic objectives since the institution of the program last September…

Notice that the expected path of monetary policy is no longer dependent only on the forecast, but on a backwards looking metric of cumulative progress, which gives rise to the notion that the Fed will taper in September on the basis of the progress to date. Things become even more complicated:

The discussion centered on the possibility of providing a rough description of the path for asset purchases that the Committee would anticipate implementing if economic conditions evolved in a manner broadly consistent with the outcomes the Committee saw as most likely.

The fact that they felt such a discussion was necessary suggested they believed that within the current forecast there was a high probability of tapering by the next press conference. Problems arise:

Several participants pointed to the challenge of making it clear that policymakers necessarily weigh a broad range of economic variables and longer-run economic trends in assessing the outlook. As an alternative, some suggested providing forward guidance about asset purchases based on numerical values for one or more economic variables, broadly akin to the Committee’s guidance regarding its target for the federal funds rate, arguing that such guidance would be more effective in reducing uncertainty and communicating the conditionality of policy. However, participants also noted possible disadvantages of such an approach, including that such forward guidance might inappropriately constrain the Committee’s decisionmaking, or that it might prove difficult to communicate to investors and the general public.

“Several” members are concerned about locking down the path of asset purchases to another version of the Evan’s rule for interest rate policy. Others suggested just such an approach, but even others caution against. Sounds like mass confusion – so out of the confusion, how did Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke end up with the 7% unemployment trigger for ending asset purchases? Was this really the committee’s view, or did he accidentally reveal his own preferences?

How did Bernanke come up with a 7% unemployment threshold? Does anyone see that number in the minutes? I want to know where that came from.

The plot thickens further:

Since the September meeting, some participants had become more confident of sustained improvement in the outlook for the labor market and so thought that a downward adjustment in asset purchases had or would likely soon become appropriate; they saw a need to clearly communicate an intention to lower the pace of purchases before long.

“Some” does not sound like a consensus, and it’s not:

However, to some other participants, this approach appeared likely to limit the Committee’s flexibility in adjusting asset purchases in response to changes in economic conditions, which they viewed as a key element in the design of the purchase program.

Moreover, there were other voices:

Others were concerned that stating an intention to slow the pace of asset purchases, even if the intention were conditional on the economy developing about in line with the Committee’s expectations, might be misinterpreted as signaling an end to the addition of policy accommodation or even be seen as the initial step toward exit from the Committee’s highly accommodative policy stance. It was suggested that any statement about asset purchases make clear that decisions concerning the pace of purchases are distinct from decisions concerning the federal funds rate.

It sounds to me like a majority at this point did not favor laying out the path for winding down quantitative easing, as doing so would be largely backward looking, nor was it obvious they could easily convince market participants that quantitative easing and interest rates were two separate and distinct policies.

So how in the world did the discussion take this turn?

Participants generally agreed that the Committee should provide additional clarity about its asset purchase program relatively soon. A number thought that the postmeeting statement might be the appropriate vehicle for providing additional information on the Committee’s thinking.

Still, there is dissent:

However, some saw potential difficulties in being able to convey succinctly the desired information in the postmeeting statement. Others noted the need to ensure that any new statement language intended to provide more information about the asset purchase program be clearly integrated with communication about the Committee’s other policy tools.

But somehow, someone is able to draw everyone but St. Louis Federal Reserve President James Bullard onto a common policy path:

At the conclusion of the discussion, most participants thought that the Chairman, during his postmeeting press conference, should describe a likely path for asset purchases in coming quarters that was conditional on economic outcomes broadly in line with the Committee’s expectations. In addition, he would make clear that decisions about asset purchases and other policy tools would continue to be dependent on the Committee’s ongoing assessment of the economic outlook. He would also draw the distinction between the asset purchase program and the forward guidance regarding the target for the federal funds rate, noting that the Committee anticipates that there will be a considerable time between the end of asset purchases and the time when it becomes appropriate to increase the target for the federal funds rate.

Again, where is Bernanke’s 7% unemployment trigger? And do you think the Committee could get Bernanke to say something that he didn’t want to say? Or do you think it more likely that after carefully listening to the various voices, Bernanke ultimately pulled the consensus in the direction he wanted it to go?

I have difficulty arriving at any conclusion that does not having Bernanke firmly entrenched on the side that felt it was very important to send a tapering message to the market sooner than later, and the only reason to do so was that he wants to ease markets into the idea of ending quantitative easing without triggering a shift in the expected time of the lift-off from the zero bound. As some of Bernanke’s colleagues recognized, however, separating the two is easier said than done.

Ultimately, the result was as expected – they would need additional data before changing the pace of asset purchases:

While recognizing the improvement in a number of indicators of economic activity and labor market conditions since the fall, many members indicated that further improvement in the outlook for the labor market would be required before it would be appropriate to slow the pace of asset purchases. Some added that they would, as well, need to see more evidence that the projected acceleration in economic activity would occur, before reducing the pace of asset purchases.

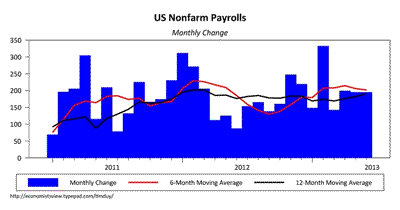

I would add that yesterday’s initial nonexistent market reaction to the minutes suggest that the last employment report pretty much seals the deal as far as tapering is concerned:

(click to enlarge)

Indeed:

However, several members judged that a reduction in asset purchases would likely soon be warranted, in light of the cumulative decline in unemployment since the September meeting and ongoing increases in private payrolls, which had increased their confidence in the outlook for sustained improvement in labor market conditions.

I tend to think that ultimately quantitative easing is mostly about labor markets and that consequently the solid strong of nonfarm payroll numbers will be sufficient to drive a September tapering, but in a bow to Bill McBride, I admit to being a little less certain.

Later in the day, Bernanke made some dovish-comments after his NBER speech. Matthew Boesler has the run-down at Business Insider:

Just because the Fed may begin tapering soon, interest rates will still be pinned at current ultra-low levels for a long time.

Bernanke said that the unemployment rate – a key indicator that will determine the future path of Fed monetary policy – probably understates the weakness in the U.S. labor market.

And from Bloomberg:

“Highly accommodative monetary policy for the foreseeable future is what’s needed in the U.S. economy,” Bernanke said today in response to a question after a speech in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

And from Paul Davidson at USA Today:

The Fed chairman also suggested that policymakers could keep the bond-buying program at full throttle longer if the economy wobbles. While the housing market is improving and buoying consumer wealth, federal spending cuts still could dampen growth, he said. “it’s still too early to say we have weathered the fiscal restraint,” he said.

The last comment is important – it suggests that forestalling the tapering process requires weaker data than we have been seeing. I tend to think this means clear evidence that the fiscal contraction is undermining the private sector. The next to last comment reminds me that the Federal Reserve believes that zero interest rates in and of themselves represent a highly accommodative policy. And the first comment is the point the Fed is struggling to drive home – ending quantitative easing does not imply an imminent rate hike. A 7% unemployment rate may be enough to justify pulling quantitative easing, but is far too high, especially given other employment data, to expect a rate hike will be around the corner.

Bottom Line: There is enough material today for everyone to walk away believing their priors. The mass confusion within the FOMC minutes alone suggest substantial factions on boths sides of the taper/don’t taper debate. That said, I think it is difficult to walk away from today’s events with a sense of certainty about the September taper. But I also think that the minutes suggest that someone brought a divided FOMC together around a common plan – a plan to put the taper on the table sooner than later but attempt to walk a tightrope with respect to interest rate policy. And I can’t see how that someone is anyone but Bernanke.

Leave a Reply