In response to the civil lawsuit filed by the US Department of Justice in February 2013, Standard & Poor’s affirms that its ratings were “objective, independent and uninfluenced by conflicts of interest”. This column presents empirical evidence opposing this claim. The data suggests a systematic rating bias in favour of the agencies’ largest issuer clients.

In its civil lawsuit against Standard & Poor’s, the US Department of Justice accuses the credit-rating agency to have defrauded federally insured financial institutions like Western Federal Corporate Credit Union:

“Standard & Poor’s, knowingly and with the intent to defraud, devised, participated in, and executed a scheme to defraud investors in RMBS [residential mortgage-backed securities] and CDO [collateralised debt obligations] tranches …” (US Department of Justice 2013).

The US complaint alleges that Standard & Poor’s presented overly optimistic credit ratings as objective and independent when, in truth, Standard & Poor’s downplayed and disregarded the true extent of credit risk: “Large investment banks and others involved in the issuance of RMBS and CDOs who selected Standard & Poor’s to provide credit ratings for those tranches” were the beneficiaries of Standard & Poor’s partial rating practices (US Department of Justice 2013).

According to the plaintiff, Standard & Poor’s catered rating favours in order to maintain and grow its market share and the fee income generated from structured debt ratings. In support of these allegations, the complaint lists internal emails in which Standard & Poor’s analysts complain that analytical integrity is sacrificed in pursuit of rating favours for the issuer banks.

Standard & Poor’s files for dismissal of the case

Standard & Poor’s denies issuing inflated ratings and any possible conflict of interest:

“From start to finish, the Complaint overreaches in targeting Standard & Poor’s, a rating agency that did not create, issue, sell or receive any interest in any security at issue in the case” (McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. and Standard & Poor’s Financial Services LLC 2013).

That some of Standard & Poor’s very own employees appealed to their colleagues and superiors to withdraw inflated ratings is dismissed as “internal squabbles” and interpreted as a “robust internal debate among Standard & Poor’s employees (McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. and Standard & Poor’s Financial Services LLC 2013). Overall, Standard & Poor’s characterises the Complaint as a “vague, generalized statement” (McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. and Standard & Poor’s Financial Services LLC 2013).

Statistical evidence on rating bias in structured products

While the US Department of Justice did not give any statistical evidence in its deposition, our new research (Efing and Hau 2013) suggests that rating favours were indeed systematic and pervasive in the industry.

In a sample of more than 6,500 structured debt ratings produced by Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s and Fitch, we show that ratings are biased in favour of issuer clients that provide the agencies with more rating business. This result points to a powerful conflict of interest, which goes beyond the occasional disagreement among employees.

The beneficiaries of this rating bias are generally the large financial institutions that issue most structured debt; they in turn provide the rating agencies with most of their fee income. Better ratings on different components (so-called tranches) of the debt-issue amount to a lower average yield at issuance – a cost reduction pocketed by the issuer bank.

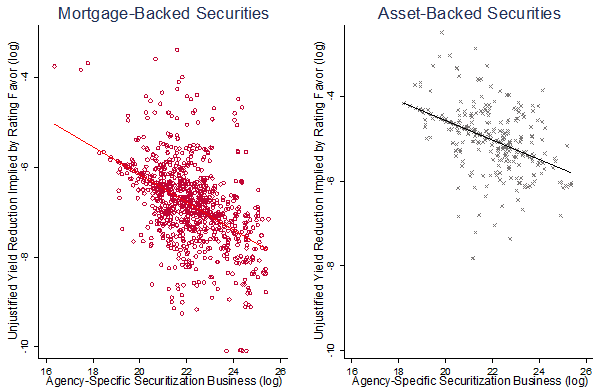

Figure 1 shows a strong correlation between the average rating-implied issuer yield and the importance of the issuer to the rating agency. The agencies’ largest clients (the x-axis) generally benefited from the largest rating-implied reduction of financing costs (the y-axis) both for mortgage-backed (left) and asset-backed (right) securities. An increase of the agency-specific securitisation business by one standard deviation is related to a (deal-level) rating improvement that reduces financing costs by seven basis points for the average deal and by 15 basis points for the 10% most risky deals.

Figure 1. Rating bias by asset type

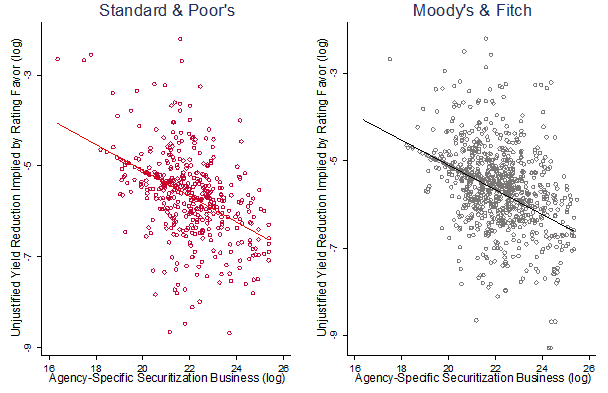

The evidence also suggests that the two other rating agencies, Moody’s and Fitch were no less prone to rating favours towards their largest clients than was Standard & Poor’s. Figure 2 shows the ratings bias separately for Standard & Poor’s (left) and Moody’s and Fitch (right). For all three rating agencies, we can reject the null hypothesis that their respective deal-level rating favours are independent from the overall rating business each agency obtained from a particular issuer.

Figure 2. Rating bias by rating agency

In its motion to dismiss the lawsuit, Standard & Poor’s points out that one would need to know the ‘true’ credit risk of a security in order show that certain ratings were “objectively false” (McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. and Standard & Poor’s Financial Services LLC 2013). Such objectivity may not be available about any individual credit rating, but a rating bias can nevertheless be revealed at high levels of statistical certainty within a large sample of ratings. Importantly, the true credit risk of a security can be proxied by observable control variables. Our regression analysis controls for collateral quality, levels of credit enhancement and issuer fixed effects. Yet inclusion of these credit-risk determinants does not destroy the statistically and economically highly significant correlation between rating favours by a particular rating agency and its securitisation business with the issuer.

Could reverse causality be at work?

Correlation evidence typically has alternative interpretations. Rating errors can also be made in good faith and banks are likely to privilege rating agencies which err in their favour and provide them with more business. Could this explain the observed correlation? In the sample, large issuers account for dozens of structured deals and only if a rating agency makes repeated rating mistakes in the same direction about the same issuer should we expect to see the correlation shown in Figures 1 and 2. In other words: The rating error of each agency must have a substantial common and directional component with respect to a specific issuer bank in order to invoke reverse causality as a plausible explanation. However, such error clustering at the level of the agency-issuer relationship is difficult to reconcile with rating errors made in good faith as these should be independent across deals and not have a common bias in the same direction.

We report a strong and highly significant Pearson (Spearman) correlation of 0.175 (0.187) between the rating errors of deals sold by issuers that provide the rating agencies with substantial securitisation business. By contrast, Low Value agency-issuer relationships do not generate a systematic rating-error correlation. For small issuers the null hypothesis of a random non-directional rating error produced in good faith cannot be rejected; it can be rejected for large issuer clients.

While a common error component (specific to deals of High Value clients) is unlikely to occur in good faith for similar deals, it is even less plausible across deals which differ in the underlying asset classes, because ratings are produced on the basis of different historical default data and methodologies. It is therefore instructive to examine separately the error correlation calculated for heterogeneous deals pairs within the same agency-issuer relationship. For High-Value agency-issuer relationships, we find a large and significant Pearson (Spearman) correlation of 0.379 (0.339) between deals that belong to different asset classes. Again such error clustering does not extend to heterogeneous deals of Small Value relationships. The strong error correlation across different collateral pools and asset classes (only for large issuers) is difficult to attribute to reverse causality or an omitted variable specific to a particular asset class.

Still more evidence on rating bias in bank ratings

Additional evidence for rating bias emerges for bank ratings. Hau, Langfield and Marques-Ibanes (2012) show in a paper forthcoming in Economic Policy that rating agencies gave their largest clients also more favourable overall bank credit ratings.

Using expected defaults frequencies of banks calculated from stock market data, we are able to calculate the rating error for more than 17,000 bank ratings of Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s, and Fitch.1 The bilateral business share in structured products between a rating agency and a bank explains the direction of the rating bias. This finding is robust to regression controls consisting of many different bank characteristics. Given that banks finance on average 20 to 30% of their balance sheet through unsecured credit, an inflated bank rating amounts to a significant benefit.

Hau, Langfield and Marqués-Ibañez (2012) also show that large banks profited most from rating favours. The banking literature so far is short of evidence for synergies that can explain why large banks had such tremendous asset growth over the last two decades relative to growth rates in the real sector. The rating process for banks may have contributed to substantial competitive distortions in the banking sector, thus fostering the emergence of the too-big-to-fail banks.

Ironies of the case

It is hard to read some of the legal arguments without being struck by a sense of irony.

In its defence, Standard & Poor’s argues (without admitting any rating bias) that it has never made a legally binding promise to produce objective and independent credit ratings. Instead, the agency describes its mission “to provide high-quality, objective, rigorous analytical information” as well as instructions to its employees like “Ratings Services must preserve the objectivity, integrity and independence of its ratings” as aspirational statements of how business should be conducted (McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. and Standard & Poor’s Financial Services LLC 2013). According to The Wall Street Journal it is almost as if Standard & Poor’s feels impelled to characterise its claims of independence and objectivity as mere “puffery” that was “never meant to be taken at face value by investors” (Neumann 2013). For an agency whose business model is based on its reputation as an impartial ‘gatekeeper’ of fixed income markets, this defence is most remarkable.

But the accusation has its own oddities: Standard & Poor’s argues that it is impossible to defraud financial institutions about “the likely performance of their own products”. Standard & Poor’s points out the irony “that two of the supposed ‘victims,’ Citibank and Bank of America – investors allegedly misled into buying securities by Standard & Poor’s fraudulent ratings – were the same huge financial institutions that were creating and selling the very CDOs at issue” (McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. and Standard & Poor’s Financial Services LLC 2013).

In many cases the victim-view on institutional investors may indeed be questionable: Large banks often issued complex securities and at the same time invested in them. It is hard to believe that the asset management division of a bank was ignorant of the dealings by the structured product division with the rating agencies. But as suggested by Calomiris (2009) and Efing (2013), the buy side for structured products might have cared less for the credit risk itself than for the rating as long as the latter was high enough to allow investment without significant capital requirements. It is difficult to figure out where exactly the border between complicity and victimhood runs.

What could be done?

The lawsuit against Standard & Poor’s highlights the conflicts of interest inherent in the rating business, but can do little to resolve them. If new and complex regulation and supervision of rating agencies provides a remedy is unclear and remains to be seen. However, three alternative policy measures could make the existing conflicts much less pernicious:

- Similar to US bank regulation under the Dodd-Frank act, Basel III should abandon (or at least decrease) its reliance on rating agencies for the determination of bank capital requirements.

- As forcefully argued by Admati, DeMarzo, Hellwig and Pfleiderer (2011), much larger levels of bank equity as required under Basel III could reduce excessive risk-taking incentives and ensure that future failures in bank-asset allocation do not trigger another banking crisis.

- More bank transparency in the form of a full disclosure of all bank asset holdings at the security level would create more informative market prices for bank equity and debt, with positive feedback effects on the quality of bank governance and bank supervision.

Our reliance on bank ratings could thus be greatly reduced.

References

•Admati, Anat R, DeMarzo, Peter M, Hellwig, Martin F and Pfleiderer, Paul C (2011), “Fallacies, Irrelevant Facts, and Myths in the Discussion of Capital Regulation: Why Bank Equity is not Expensive”, Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford University Working Paper No. 86, MPI Collective Goods Preprint, No. 2010/42.

•Charles, W (2009), “The Debasement of Ratings: What’s Wrong and How We Can Fix It”, Working Paper, Columbia Business School.

•Efing, Matthias (2013), “Bank Capital Regulation with an Opportunistic Rating Agency”, Swiss Finance Institute Working Paper No 12-19.

•Efing, Matthias, and Hau, Harald (2013), “Structured Debt Ratings: Evidence on Conflicts of Interest”, Swiss Finance Institute Working Paper No. 13-21, available at SSRN.

•Hau, Harald, Langfield, Sam, and Marques-Ibanez, David (2013), “Banks’ Credit Ratings: What Determines their Quality?”, Economic Policy, 28(74), 289-333.

•McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. and Standard & Poor’s Financial Services LLC (2013), “Memorandum in Support of Defendants’ Motion to Dismiss the Complaint Pursuant to FED”, R CIV P 9(b) and 12(b)(6).

•Neumann, Jeannette (2013), “Standard & Poor’s Has Unusual Defense”, The Wall Street Journal, 22 April.

•US Justice Department (2013), “Complaint for Civil Money Penalties and Demand for Jury Trial”, US District Court, Central District of California, Case No CV13-00779.

__________

1 The expected default frequency data was acquired from Moody’s and used as supplied. Moody’s therefore cannot claim that this rating benchmark is meaningless as it commercially sells this product.

Leave a Reply