There’s a lot of discussion now about the role of the GSEs in “the crisis.” Unfortunately, not everyone is talking about the same crisis. Some are talking about the housing bubble/crash, some are talking about the late 2008 financial crisis, and I believe both groups have the 2011 unemployment crisis in the backs of their minds (otherwise why is the debate seen as being so important?) After all, there is no similarly high-charged debate over the auto crisis/bailout/sales slump.

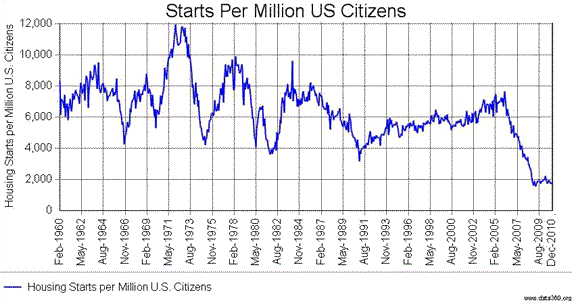

Let’s start with the housing crisis. A major theme of the Austrians is that too many houses were built in the mid-2000s, and the resulting slump has led to high unemployment. Here are US housing starts per capita going back to 1960:

As you can see, housing starts over the last decade have been far below the level of previous decades. We certainly don’t have a weak housing sector in 2011 because an extraordinarily large number of homes were built in the past decade. Rather it seems the recession has caused many families to double up. BTW, I will concede that we built too many homes in the mid-decade period, so I don’t completely deny the Austrian story. I just don’t think too many houses is the huge ”crisis” most people are talking about.

Instead, it seems to me that both sides of the GSE debate tacitly accept that lax lending standards due to either:

1. deregulation and moral hazard causing banks to take excessive risks, or

2. the GSEs and other federal housing rules, regulations, tax breaks, etc.,

caused a housing price bubble in the mid-2000s. When this bubble collapsed, it created a severe banking crisis, which then led to a severe recession.

I believe this is mostly wrong. I’ll concede that part of the housing bubble was due to the factors mentioned above (both banks and the GSEs played a big role.) But the link between the housing bubble and the severe financial panic is much weaker than people realize. And the link between the severe financial panic and high unemployment in 2011 is almost nonexistent.

The mistake both sides make is to look for monocausal explanations. Here’s what the facts show:

1. The economics profession almost entirely disagrees with me. Yet in mid-2008 the consensus view of the economics profession was that we were NOT going to have a severe financial crisis and we were not going to have a severe recession. Indeed growth was forecast for 2009, along with moderate unemployment. And yet the scope of the subprime crisis was almost completely understood by that time.

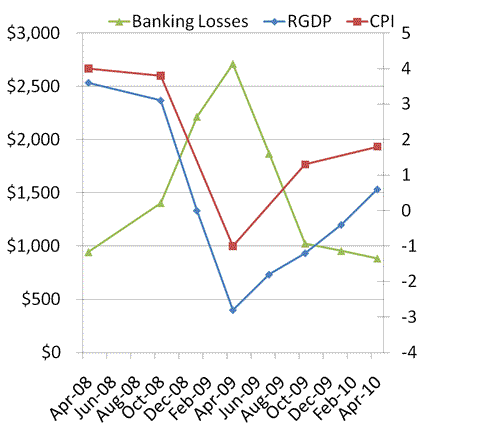

After things blew up, Bernanke was mocked for early statements suggesting that likely subprime losses, even in the worst case, were not large enough to bring down the US banking system. But of course he was right. Here’s what actually happened:

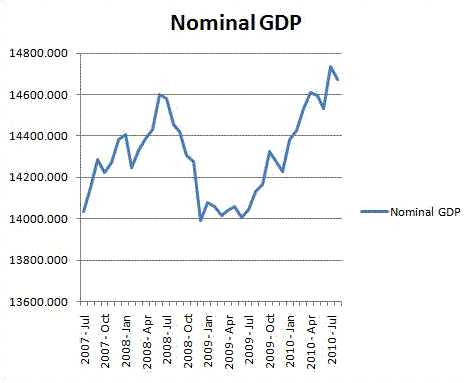

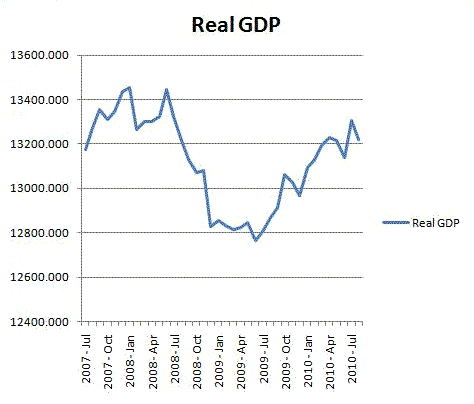

1. Between June and December 2008 both NGDP and RGDP fell sharply.

2. The cause of the fall in RGDP was the fall in NGDP

3. NGDP fell at the fastest rate since 1938 because the economy was already sluggish due to the housing slump, which reduced the Wicksellian equilibrium rate of interest. Ditto for oil and auto sales. Normally the Fed would cut rates enough to prevent a recession. But this problem coincided with a severe commodity price shock, which drove up headline inflation and frightened the Fed. They did not cut rates once between April and October, by which time the great NGDP and RGDP crash was nearly two thirds over.

4. The big NGDP crash dramatically reduced almost all asset values in the second half of 2008. About half way through this crash, the severe phase of the banking crisis started. This doesn’t mean the earlier subprime fiasco played no role. It did greatly weaken the system in 2007 and early 2008. So the GDP crash was imposed on an already weakened banking system. A cold turned into pneumonia. GDP fell even faster.

5. Estimated losses to the entire US banking system soared during this crash, and peaked in early 2009 at roughly $2.7 trillion, only a modest fraction of which were subprime mortgages. Then expected growth rates recovered somewhat, asset values partially recovered, and estimated losses to US banking fell back under a trillion. So the proximate cause of the financial crash was tight money which drove NGDP expectations much lower, although the earlier subprime fiasco certainly created an environment with a low Wicksellian equilibrium rate, making monetary errors much more likely. And of course when rates hit the zero bound (which by the way didn’t occur until the great GDP crash had ended in December!!) the Fed had an even more difficult time steering the economy.

6. To summarize, the severe financial crisis could not have caused the great GDP collapse, because monthly GDP estimates show it was half over before the post-Lehman crisis even began. But even if this view is wrong, there is not a shred of theoretical or empirical evidence linking the current 9.2% unemployment with the 2008 financial crisis. Theory suggests that if a central bank inflation targets, it drives NGDP. The Fed says it has the economy where it wants it (in nominal terms), and doesn’t think we need more inflation. When it did think we needed more inflation mid-2010 (when the core rate had fallen to 0.6%) it did QE2, which raised core inflation back up to roughly where the Fed wanted it. Of course (just as in mid-2008) commodity price inflation is distorting Fed policy, but that’s a problem attributable to the Fed, not the financial crisis.

This graph shows how IMF estimates of total US banking losses are inversely correlated with expected total inflation and RGDP growth in 2009 and 2010.

I see three separate crises. A “misallocation of resources into housing crisis,” a “federal bailout of banks crisis,” and a high unemployment crisis. Who’s to blame for each?

1. The private banking system and the GSEs both played a major role in causing too much housing to be built in the mid-2000s. The errors of the private banking system were due to both misjudgment (they did lose money after all) and bad incentives (moral hazard due to various government backstops.) Pretty much the same is true of the GSEs, although their role has always been a bit more politicized, and Congress must accept some blame for pushing them to boost the housing market. But this was a modest problem, as the first graph shows. It’s not the “real” issue that the left and right is debating so vigorously.

2. The GSEs are far more to blame than the banks for the bailout problem. And the banks most to blame are often smaller banks that made loans to developers, not the more famous subprime mortgages. Last time I looked the estimated losses to the Treasury from the GSEs was a couple hundred billion, from the smaller banks (i.e. FDIC–which is financed by taxes, BTW) was over a hundred billion, and the big banks was near zero (depending on how much they lose on Bear Stearns.) That’s all you need to know about where to apportion blame for the bailout crisis.

3. As far as the high unemployment crisis, the proximate cause is low NGDP, which means the Fed is to blame. Then we can apportion some blame to Obama for not putting more of his people on the Fed, and not doing it sooner. But ultimately we macroeconomists are to blame, as both the Fed and Obama take their lead from us. We were mostly silent on the need for vigorous monetary stimulus in the last half of 2008, and many have remained silent ever since.

The hero is the EMH, as markets warned the Fed that money was way too tight in September 2008.

In the history books it says the 1929 stock market crash triggered the Depression. After an nearly identical crash in 1987 had zero effect on GDP, we learned that was false. But it’s hard to blame historians for connecting a high profile financial collapse, with an economic collapse that was barely underway, and suddenly got much worse. Economists should know better.

Here’s the GDP data I referred to (from Macroeconomics Advisers):

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply